![]()

1

WHAT IS A STATION?

Confusion often exists between the terms “station” and “depot.” As defined in railway timetables, a “station” is a “stopping place” and need not be a structure. In fact, it may be nothing more than a siding, a platform, or a mail hook. “Depot,” an American term, refers to the building itself. Nevertheless, in Canada the word “station” popularly refers to that wonderful old building, with its semaphore, its bay window, its platform, and its waiting room full of memories.

No matter what it was called, the station was vital for train operations and for customers. On the operational side, it housed offices for administrators, provided sidings and yards for rolling stock, maintenance and fuel for the locomotives, equipment for the orderly movement of trains, and shelter and food for the train crews. The station was a place to work, to live and to play; it was the architectural pride of the community, and was the building that, more than any other, determined the layout of the community. But its fundamental role was to serve the railway and to serve the customer, and everything about the layout, the location, and the equipment of the station, supported these two functions.

For its customers, the station was where they shipped parcels, bought money orders or sent telegrams; it was where they picked up their mail or loaded their farm produce; it was where they hurried down a meal during crew changes; it was where they bought their tickets for a trip around the world or just to the next town, and it was where they awaited the train that would take them there.

Clearly, a station could be many things, and the number of functions it had determined what kind of station it was. A station could range from something as simple as shelter for passengers with a platform for freight and a mail crane, to a large urban palace with everything from executive suites to shoeshine stands. In between were the divisional stations, and the most common of all, the way stations.

The Country Stations

Also known as way stations, or operator stations, it is the country stations that many small-town residents still remember. After all, nearly every town had one. All the jobs the railway had to perform in a small town were there, packed under one roof. They remember the agent’s office with its barred window, the large oak desk with its typewriter, telegraph and telephone, and the piles of forms everywhere. Outside, they remember the wooden semaphores perched at various angles, the water tank looming down the track, the farm products piled high on the platform, and the canvas bags bulging with mail resting on the wagon. And they remember the waiting room with its smell of kerosene and the sound of the ticking clock.

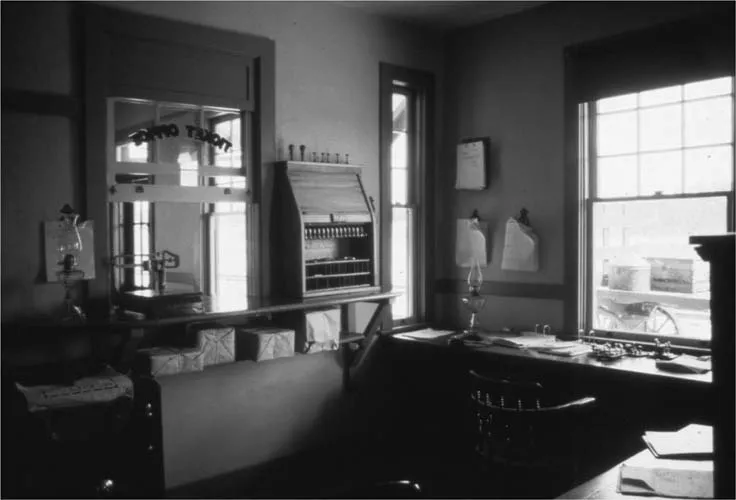

A typical agent’s office has been preserved in the Bellis, Alberta, station. Photo by the author.

Because so much was packed into the little buildings, the layout was critical. All services had to be arranged within the building so that passengers, freight, and mail were all handy to the agent. And always within reach were the train order crank, the typewriter, and the telegraph key, all indispensable for train movement.

The Agent’s Office

The heart of the operation was the agent’s office, usually located in the centre of the station. A bay window protruded from the office, out over the platform to allow the agent to see down the track and to keep his eye on the platform. On the desk, set into the bay, was the all-important telegraph key. Here, the information clattered through from the dispatcher’s office to let the agent know when a train was on the way. To one side of the office was the ticket window, barred to discourage thieves, where passengers would buy their tickets or just come to chat. On the other side was the entrance to the freight room where express parcels, mail, and freight waited beside the milk cans and egg crates for shipment to the next town. Each section had separate doors on to the platform and usually separate entrances from the street. Behind the office was the door that led to the agent’s quarters.

The Port Stanley, Ontario, station displays an early style of order board. Photo by the author.

Station operation depended as much upon what was outside the station as what was inside. The station building was often surrounded by a clutch of smaller structures. Because many early stations lacked basements, a separate shed was added to store the coal or wood that the agent used to heat the building.

In remoter locations where no permanent settlement had sprung up by the track, the station was often a house for the operator and his equipment. In such areas, section houses sometimes doubled as stations.

The Wooden Arms

Another feature firmly fixed in the memories of many Canadians is the wooden order boards, or semaphores, one red and one green, poised at various angles from a pole above or beside the bay window. They gave the locomotive engineer his instructions on whether to stop or to proceed without stopping.

Originally there were no train order boards. Engineers were required to stop at each station and sign for their orders. On some early railway lines a ball placed on top of a pole before the station gave the engineer permission to continue full speed ahead. The term “high balling” originated with this device and has remained in the railway lexicon ever since.

The first boards were, as the name implies, flat boards with white spots painted onto a red background. Oval in shape, the boards pivoted on a spindle and were controlled by a chain that was attached to a lever inside the agent’s office. When the board was parallel to the track, it was a “clear board” and the engineer could proceed without stopping. When the board was perpendicular to the track, the engineer must stop. Atop the spindle were red and green glass covers in front of a lamp. When the board was in the stop position the red glass covered the lamp. The “clear board” placed the green glass before the lamp.

Ontario’s relocated Kleinburg station still has the later style semaphore. Photo by the author.

With the introduction of the order board, the engineer no longer had to stop the train and enter the station to receive his orders. Instead, he simply slowed the engine while the agent handed them up on the end of a long hoop or fork.

By the 1880s the order board had largely been replaced by the semaphore. Invented by a French schoolboy during the Napoleonic Wars, the semaphore soon became a universal method of long-distance signalling. The early semaphores were two-directional lower-quadrant semaphores. These were eventually replaced by upper-quadrant semaphores, which pointed either up, straight out, or at a forty-five-degree angle. Up meant “go,” out meant “stop,” and the angle meant “slow.” If by some accident the mechanism broke, the arm would automatically fall into the “stop” position.

At the tiny station of Lorneville Junction, in central Ontario, the order board, located at a distance from the station, mysteriously always ended up in the “stop” position, much to the frustration of train conductors. The mystery was solved when it was discovered that a local pig, fond of sticking his snout into the signal mechanism’s grease, was releasing the cog, allowing the arm to fall into the “stop” position. (This delightful anecdote is recounted by Charles Cooper in his history of the Toronto and Nipissing Railway, Narrow Gauge For Us.)

Passengers wait in the Carleton Place waiting room with the typical hard benches. Photo courtesy of CP Archives, A-13170.

The Waiting Rooms

The thing that many Canadians remember most about waiting for the train is the room where they waited. Outside the home, Canadians frequented the station waiting room more than any other room in their communities. They knew its smell, the smell of the wood stove in the winter, or the kerosene from the lamp. There was also the smell of the oil rubbed into the floor; and many knew that the screen doors that would slam upon them before they could flee through the inner door. They knew the sounds … the ticking of the clock, the chattering of the telegraph key and, finally, the distant whistle of the long-awaited train.

No matter how they tried, Canadian rail travellers of the time could never forget the benches. With the square or curved backs, the benches were, as one writer recalls, “the reason you saw so many people walking up and down on the platform waiting for the train.” The CPR even had standard designs for benches, one with thin horizontal slats for use at smaller stations, and sturdier benches with wide vertical slats for “the better class stations.”

Larger stations provided separate waiting rooms for ladies and men and perhaps still a third for smokers. During segregation in the southern United States, small waiting rooms on the back of the station divided black passengers from white.

While waiting, the passenger could glance at the bulletin board located just outside the waiting-room door where the agent would post the scheduled arrival time. The Railway Act required that the arrival and departure times be written with white chalk. Failure to do so earned the agent a $5 fine plus demerits.

The Mail

Another familiar sight at the country stations was the mail cart. As the train whistle wafted from a distant crossing, the agent would wheel a creaking cart, loaded with grey canvas sacks bulging with the outgoing mail, across the wooden platform to the edge of the track.

Almost as soon as a railway opened its line it assumed mail service from the slower stagecoaches. By 1858 the Grand Trunk Railway was carrying mail between Quebec and Sarnia, the Great Western was hauling the sacks between Niagara Falls and Windsor via Hamilton, the Central Canada carted the loads between Brockville and Ottawa while the Northern moved it between Toronto and Collingwood.

The many gaps that remained in the evolving network continued to be filled by stagecoach and steamer. In 1863, as the gaps filled in, the government introduced travelling post offices. Now the trains could not only carry the mail, but sort it right on the train. Special mail cars were fitted with sorting tables, destination slots, and even washing and cooking facilities. This speeded up the procedure to the point where a letter could be posted and not only delivered the same day, but, if there was frequent train service, a reply could be received the same day as well.

The mail doesn’t always move quickly. These bags are piled up during a mail strike in the 1920s. Photo courtesy of Metro Toronto Reference Library, T32360.

In 1868, Timothy Eaton, owner of the famous Toronto department store of the same name, introduced the mail-order system. Through his catalogue, a Canadian anywhere could order an item and Eaton’s would send it by train. Thus began a Canadian institution that would last over a century.

By 1910 most of the gaps had been filled and nearly every Canadian could send or receive mail by rail. The trains became rolling post offices. Inside the lurching mail cars, sorters pored through the sacks, separating the mail for the next stations. If the train was approaching a flag stop with no passengers to board, the sorters would wrestle open the door and give the mail sack a hefty kick. On o...