- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Often condemned as a form of oppression, fashion could and did allow women to express modern gender identities and promote feminist ideas. Einav Rabinovitch-Fox examines how clothes empowered women, and particularly women barred from positions of influence due to race or class. Moving from 1890s shirtwaists through the miniskirts and unisex styles of the 1970s, Rabinovitch-Fox shows how the rise of mass media culture made fashion a vehicle for women to assert claims over their bodies, femininity, and social roles. She also highlights how trends in women's sartorial practices expressed ideas of independence and equality. As women employed new clothing styles, they expanded feminist activism beyond formal organizations and movements and reclaimed fashion as a realm of pleasure, power, and feminist consciousness.

A fascinating account of clothing as an everyday feminist practice, Dressed for Freedom brings fashion into discussions of American feminism during the long twentieth century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dressed for Freedom by Einav Rabinovitch-Fox in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Mujeres en la historia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER ONE

Fashioning the New Woman

Gibson Girls, Shirtwaist Makers, and Rainy Daisies

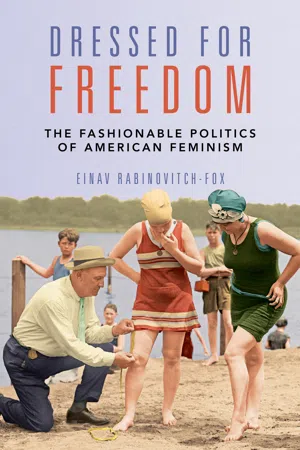

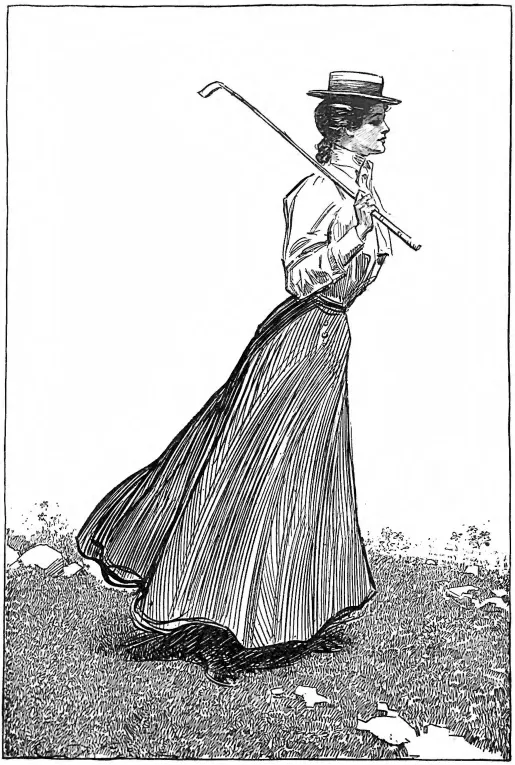

During the last decade of the nineteenth century, a new image of feminine beauty emerged from the pages of popular magazines such as Collier’s Weekly, Life, and Ladies’ Home Journal. Typified by the work of the illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, the young American girl was depicted as a young, White, tall, single woman, dressed in a shirtwaist and a bell-shaped skirt, with a large bosom and narrow, corseted waist. While it would take Gibson a few years to refine this image, by the mid-1890s the Gibson Girl, as the image came to be known, would become so popular that her influence exceeded the pages of magazines, and she became a cultural and a fashionable icon (figure 1.1).1 Embodying ideas of mobility, freedom, and modernity, the Gibson Girl and her fashions symbolized the changes in women’s social roles and public presence in this period. According to the feminist Charlotte Perkins Gilman, the Gibson Girl was the perfect realization of a “New Woman”—“a noble type” that represented women’s progress. “Not only [does she] look differently, [she] behave[s] differently,” Gilman argued in her 1898 book, Women and Economics. She was full of praise for this New Woman: “The false sentimentality, the false delicacy, the false modesty, the utter falseness of elaborate compliment and servile gallantry which went with the other falsehoods,—all these are disappearing. Women are growing honester [sic], braver, stronger, more healthful and skillful and able and free, more human in all ways.”2

FIGURE 1.1: Embodying values of youth, movement, and modernity, the image of the Gibson Girl became associated with the period’s social and cultural changes, especially women’s growing opportunities in work, education, and consumer culture. (Charles Dana Gibson, “School Days,” Scribner’s Magazine, November 1899)

The New Woman emerged from the social and cultural changes in turn-of-the-century United States, especially White middle-class women’s growing opportunities for work, education, and engagement with consumer culture. Representing a generation of women who came of age between 1890 and 1920, she became associated with the political agitation of women in this period, and her image was often conflated with those of the suffragist or the feminist.3 As both an image and a cultural phenomenon, the New Woman offered a way not only to understand women’s new visibility and presence in the public sphere, but also to define modern American identity in a period of unsettling change.4 In her behavior and looks, she challenged gender norms and structures while projecting a distinctly modern appearance. The New Woman was often contrasted with the passive, frail, pale, delicate image of the Victorian “True Woman,” who was usually depicted dressed in wide skirts, swathed in draperies and petticoats. Unlike the True Woman, who embodied an essential, submissive, and domestic concept of femininity, the New Woman represented a contemporary, modern understanding, one that emphasized youth, visibility, and mobility, as well as a demand for greater freedom and independence.5

This chapter examines how the Gibson Girl and her fashions became a tangible means through which women could imagine and define their identities as New Women. Although the Gibson Girl was a fictional figure, appearing as a black-and-white illustration, the commercialization and popularity of her fashions across class and racial lines enabled different women to shape her image and expand its liberating meaning. White college students used the Gibson Girl imagery to convey their political support for suffrage while maintaining their standing as respectable bachelorettes. African American women also adopted and adapted the Gibson Girl fashions, capitalizing on the image’s respectability to demand access to privileges of White ladyhood. Working-class immigrants, who were both producers and consumers of the shirtwaist that became associated with the Gibson Girl, harnessed it as part of their identities as workers and Americans who deserve their rights. Other middle-class business professionals employed the Gibson Girl’s association with athleticism, and the bicycle in particular, to advance ideas regarding women’s dress, promoting comfortable clothing for everyday wear. Together, these women not only created a “new look” for the New Woman but also used fashion to shape her meanings and political message, connecting the rise of mass consumer culture and media to new ideas and experiences of freedom for women.

Indeed, fashion played a crucial role in shaping the meaning of the New Woman. The period’s popular fashions that became the Gibson Girl’s trademark were also the ones that turned her into an archetype of the New Woman. But more than that, they, and the activities they enabled, were what made her modern. The great novelty of the Gibson Girl outfit was in the introduction of the “ensemble”: a separate shirtwaist and gored bell-shaped skirt that were mass-produced in standardized sizes. The versatility of the ensemble separates enabled women to construct different outfits by using one skirt and several shirtwaists or vice versa, all tailored to the wearer’s taste and financial resources. It also brought changes to women’s attitudes toward their wardrobes, allowing them to dress in one functional outfit throughout the day and still maintain respectability.6 Perhaps more importantly, the availability of the ensemble separates also contributed to a new conception of the female body, which was much more mobile. With the increasing participation of women in sports and leisure, the ensemble—now modeled as a combination of a shirtwaist and a relatively short bicycle skirt—constructed not only a new experience but also a modern understanding of womanhood.

The functionality of the ensemble and its suitability to multiple occasions, contributed to the blurring of class distinctions, serving as a democratizing force. As women across society adopted the ensemble and capitalized on its fashionability, they established the American New Woman as a well-dressed “average woman,” an image that was available to multiple groups of women to claim.7 By focusing on the influence of the shirtwaist and the short bicycle skirt, this chapter analyzes how these ensemble items became crucial to the understanding of modern femininity at the turn of the twentieth century. Through these clothes, New Women advanced their ideas of freedom and mobility, adopting and adapting the styles according to their own resources and the particular goals they wanted to pursue. In their appropriation of the Gibson Girl style, New Women thus took an active role in redefining their place in society, turning fashion into an empowering force and a political means.

However, while the Gibson Girl and her appearance signaled a shift from previous fashions, the shirtwaist and the bicycle skirt did not represent a revolution in styles so much as an evolution. The ensemble outfit did not eliminate corseting or challenge gender conventions in overt ways. Even when these clothing were endowed with political meanings or stood for women’s independence of mind and their demands for freedom, the commercialization and popularity of these fashions also shaped the boundaries of their feminist promise. Unlike the previous generation of woman’s rights advocates who experimented with alternatives to the mainstream, New Women at the turn of the twentieth century sought to gain incremental advancement within the current fashion system. Their goal was to create an image that would be both liberating and fashionable, and as such they sought to harness the popular trends, not to challenge them.

In fact, the New Woman’s fashions became symbolic of the transitional moment women experienced at the turn of the twentieth century. Much was clearly changing. As women entered higher education and the labor force, they increasingly demanded taking an equal part in the political sphere. They adopted new behaviors and gender norms that increased their physical movement and visibility in public. Yet women still faced significant obstacles in breaking into traditionally male-dominated professions, in balancing a marriage with a career, and in claiming political and social equality. The New Woman, with her shirtwaist and bicycle skirt, both epitomized these changes and alluded to the limitations, simultaneously sanctioning and undermining women’s new social and cultural status. Her fashionableness, facilitated by the popularity of the Gibson Girl, enabled a push for greater freedoms, but it also stirred the New Woman from radicalism in favor of a more commercialized approach. Fashion thus not only facilitated women’s physical movement in this period, or reflected the new roles they claimed for themselves. It also shaped the liberating meanings of the New Woman and the possibilities she had.

The Gibson Girl as a Fashionable New Woman

When she first appeared in the pages of the Century in 1890, it was not apparent that the Gibson Girl would become the face of an entire generation.8 Other illustrators such as Harrison Fisher, Howard Chandler Christy, and Coles Phillips also created versions of the “American Girl.” Yet, by 1900, the Gibson Girl surpassed its competitors in popularity, becoming one of the most marketed images of the time, appearing in advertising and on a myriad of consumer products, including wallpaper, silverware, and furniture.9 In addition, magazines and pattern companies advertised “Gibson skirts” and “Gibson waists,” as well as fashion accessories such as hats, ties, and collars inspired by the Gibson Girl.10

Gibson’s success in turning his Girl into an archetype of New Womanhood rested on his ability to use her image to reflect the values of the period, and at the same time to capture the changes in them. As a product of the printed media, which catered to middle-class audience, the Gibson Girl was the epitome of the White middle-class woman.11 She often appeared outdoors, engaged in an athletic or leisure activity such as golf or cycling, or depicted in social activities such as dances and dinner parties, all of which suggested her bourgeois origins. The Gibson Girl was never portrayed performing any kind of labor, and Gibson himself presented her not as a working-class factory girl, but rather as a lady of leisure or as a middle-class college debutante.12

Indeed, Gibson constructed the Gibson Girl according to his understanding of what the ideal American woman at the turn of the twentieth century should look like. He used her image to demarcate the boundaries of the social freedoms that women were beginning to enjoy in the late nineteenth century, framing them in nonthreatening commercial terms. In his quick pen-stroke style, the “type” that the Gibson Girl embodied was one that was definitely modern, but not too radical. On the one hand, she represented a confident and assertive type of woman who was a potential challenge to existing sexual hierarchies and gender roles. Gibson usually depicted her in more modern form of relationships with men—often unchaperoned and in fairly equal settings—and almost always as single, not as a married woman or a mother.13 By presenting the Gibson Girl as flirtatious while never portraying the fulfillment of her courting endeavors, Gibson alluded to the liberating possibilities that New Womanhood entailed. Yet, on the other hand, Gibson framed the New Woman’s challenge as playful romanticism in relationships with men, not as a demand for political rights. He portrayed her as an object of men’s desire, not vice versa. The freedom the Gibson Girl represented was a matter of style rather than substance, intended to ultimately find a suitable match, not eschewing societal or gender expectations.14

The commercialized non-radical femininity of the Gibson Girl was especially evident in the fashions she was depicted in. Despite offering a new degree of comfort and mobility, and despite being more masculine in look, the clothes she wore did not pose a serious threat to prevalent gendered notions, but remained within the boundaries of acceptable feminine appearance. Whereas Gibson quickly adopted the athletic ideal of the shirtwaist and separate skirt as the Gibson Girl’s signature outfit, he also depicted her wearing voluminous evening gowns that did not facilitate much movement. Moreover, she always appeared corseted, and even when depicted outdoors she usually wore the appropriate sports attire, which always meant skirts and not bloomers. Yet, precisely because the Gibson Girl’s clothing did not mark a break with mainstream styles, they enabled New Women to challenge gender notions and to claim new public roles without being reprimanded as radical feminists like their foremothers.

Although she was not associated with politics, the Gibson Girl represented two other main developments that contributed to the emergence of the New Woman and her challenge to the gender system in the 1890s: women’s entrance into higher education and their engagement with sports. As a young, fun-loving, single woman who engaged in popular outdoor activities, the Gibson Girl was the perfect embodiment of the college girl, or the “co-ed.” In an illustration titled “School Days,” the Gibson Girl almost floats above the ground, wearing a tailored shirtwaist and gored walking skirt, produced through triangular-shaped panels sewn up together. Holding a golf club, rather than books, the Gibson Girl’s ensemble marked a new sense of mobility and legitimacy of women’s collegiate lifestyle (figure 1.1).15 However, the depiction of the Gibson Girl as a harmless college girl represented not so much acceptance of women’s entrance into higher education, as an attempt to deflate this very social change.16 Even the identification of the Gibson Girl with girlhood, as her name indicated, suggested high-spiritedness, not political determination, undermining the potential threat that the association of the Gibson Girl with the New Woman might have otherwise entailed.17

Nevertheless, young students, particularly those for whom college marked the beginning of a career in suffrage or social reform, capitalized on the popularity of the Gibson Girl to gain legitimacy for their status as educated women and reformers. In...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction. Beyond Bloomers: The Feminist Politics of Women’s Fashion in the Twentieth Century

- 1. Fashioning the New Woman: Gibson Girls, Shirtwaist Makers, and Rainy Daisies

- 2. Styling Women’s Rights: Fashion and Feminist Ideology

- 3. Dressing the Modern Girl: Flapper Styles and the Politics of Women’s Freedom

- 4. Designing Power: The Fashion Industry and the Politics of Style

- 5. This Is What a Feminist Looks Like: Fashion in the Era of Women’s Liberation

- Epilogue. The Fashionable Legacies of American Feminism

- Notes

- Index

- Back Cover