- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Featuring multidisciplinary research by an international team of leading scholars, this volume addresses the contested aspects of arabesque while exploring its penchant for crossing artistic and cultural boundaries to create new forms. Enthusiastically imported from its Near Eastern sources by European artists, the freely flowing line known as arabesque is a recognizable motif across the arts of painting, music, dance, and literature. From the German Romantics to the Art Nouveau artists, and from Debussy's compositions to the serpentine choreographies of Loïe Fuller, the chapters in this volume bring together cross-disciplinary perspectives to understand the arabesque across both art historical and musicological discourses.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Arabesque without End by Anne Leonard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & History of Art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1Spatchcocking the ArabesqueBig Books, Industrial Design, and the Captivation of Islamic Art and Architecture

Margaret S. Graves

DOI: 10.4324/9781003015949-2

Spatchcock: a culinary term, met in cookery books of the 18th and 19th centuries, and revived towards the end of the 20th … used to indicate a summary way of grilling a bird after splitting it open down the back and spreading the two halves out flat.(The Oxford Companion to Food, 3rd ed.)

These days, many scholars of Islamic art would probably avoid calling anything an “arabesque.” The word carries so much Orientalist baggage that it is almost impossible to maneuver, and besides, there are plenty of terms available that are more precise (if less evocative), like “foliate scrollwork” or “curvilinear designs.” Indeed, it is frustratingly difficult to say what is meant by the arabesque under any circumstances. The term seems to appear first in early-sixteenth-century Europe, with arabeschi and moreschi used as seemingly interchangeable pattern-book descriptors for the complex curvilinear designs made by craftsmen in Venice and other mercantile centers in response to those they encountered on imported metalwares and leather goods from the Middle East and North Africa.1 The very idea of an “arabesque,” therefore, has from its inception been fully synthetic, born out of commercial interactions between Europe and the Islamic world: attempts to locate a “true source” in the Islamic world are compromised from the outset.2 Furthermore, as other chapters in this volume show, many European conceptions of the arabesque had detached themselves from any reference point in the Islamic world long before the nineteenth century began, performing their own distinct evolutions and involutions through the spheres of literature, music, and visual art ever since.

In point of fact, the curvilinear designs executed by artists of the Islamic world on buildings, books, and objects are not merely dissimilar from the Euro-American artistic arabesque. In many ways, they are the polar opposite of the sinuous, meandering lines of the Nabi painters or the open-ended oscillations of Poe’s literary arabesque. The formal repertoire of curvilinear vegetal designs varied hugely across the Islamic world, but generally speaking, the factors governing their arrangements are as significant as the motifs themselves. Most often, the craftsmen of the pre-modern Islamic world used precise geometric principles, repeating formulae, and planar symmetry to construct taut systems of curvilinear design that could extend and articulate both surface and space. Those systems, though in some cases potentially limitless, were controlled with rigor and have been likened to the Arabic language itself in their progressive generation of form from root principles.3 Typically, they present the viewer with a tightly constructed totality lying very far indeed from the wiggly, indeterminate convolutions of the arabesque that haunted the nineteenth-century European imagination.4

For these reasons, the trajectory of the curvilinear designs termed “arabesques” within modern European applied design was somewhat different from their passage through the so-called high arts. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, arabesque forms, including many drawn from Islamic art and architecture, reached European audiences through large-format print publications that isolated and collated motifs from a tremendous variety of sources. The most famous of the universal design sourcebooks from that period is Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament (1856), but there were many other related volumes in circulation by the end of the century. Although Jones and other theorists of ornament took some of their Islamic motifs from two-dimensional manuscript traditions, most often they presented roundels, borders, and panels of repeating patterns that had been extracted from architectural decoration or sometimes three-dimensional artworks in metal or ceramic. During the same period, other types of publication also sought to capture the highly complex systems of architectural ornament found upon historic Islamic buildings as the emerging realms of archaeology and national heritage were shaped by European and later Ottoman imperialism. Three-dimensional monuments were rendered into two-dimensional imagery—all in the name of scholarship and, less overtly but no less importantly, nation-craft and territorial interests.

One of the things all these print projects have in common is the way that they cleave ornament from the third dimension. Motifs that originally articulated volumetric surfaces were isolated, flattened, and pinned against the page in order to facilitate their preservation in print media and their reuse in industrial design, inevitably losing much of their material complexity and spatial coherence in the process. In this way, such publications elided one of the most interesting and important aspects of ornament in Islamic art: its interaction with the third dimension. Rather than being an arbitrarily applied skin, skilled ornament in the pre-industrial Islamic world is predicated on meaningful and mutually constitutive relationships with the three-dimensional form of the object or building on which it appears. This is made possible by what I have termed elsewhere “the intellect of the hand,” a premise that recognizes the interconnection of the mental, manual, and sensory faculties in the act of craftsmanship.5 Thus, the intelligent and responsive manipulation of plastic materials—stucco, stone, ceramic, wood, metal—creates modes of ornament that are spatially and materially complex and satisfying. Those achievements become largely obscured when architecture and the art of the object are translated into the two-dimensional plates of print publishing, reducing the experiential and intellectual aspects of three-dimensional ornament to solely graphic terms.

This chapter will show how, by spatchcocking the arabesque, splitting it from form and flattening it against the page, nineteenth-century theorists of ornament and their publications minimized the cognitive dimensions of Islamic ornament and obscured the extent of the craftsmen’s achievements. At the same time, those nineteenth-century publications established a modernist paradigm of two-dimensionality for ornament that still dominates today. In the following sections, I will reconstruct the spatchcocking of the arabesque through big books of architectural data and universal design compendia, following those books as they canonize Tulunid architectural decoration in Cairo, construct ethnic evolutionary lineages of curvilinear design, and translate three-dimensional artworks into two-dimensional reproducible commodities.

Architectural Capture: Cairo, Granada, Bursa

In their art-historical studies of European encounters with Islamic ornament, Gülru Necipoğlu and Rémi Labrusse rightly point to two major genres of illustrated publication—both of them quintessentially nineteenth-century undertakings—that shaped European perspectives on the arabesque.6 One is the universal handbook of ornament typified by Jones’s Grammar of Ornament, a visual-technical-literary form that will be discussed below. The other genre, which preceded and commingled with the fully-fledged industrial design sourcebooks of Jones and others, could be called the architectural superbook.

Large in format, luxuriously produced, abundantly illustrated, and usually published in installments, these elephantine superbooks recorded architectural heritage in the newly colonized territories of the Middle East and North Africa. Some included dramatic color plates made possible by the newly developing technologies of chromolithography available from the late 1830s onward, and although they are now associated primarily with the names of individual authors and artists, each also represents the work of a team of engravers and lithographers. The genre was dominated by Frenchmen, many of them benefiting from state support. The books gave particular attention to the monuments of Egypt—especially Cairo—following the famous multivolume Description de l’Égypte, published by decree of Napoleon in 1809–1829. The medieval monuments of Islamic Spain also garnered substantial attention as the most accessible Islamic architecture for western Europeans. Through their image programs, these superbooks canonized the architectural decoration of two monuments in particular as touchstones of the arabesque: the Nasrid palaces of the Alhambra in Granada (fourteenth century) and, less obviously but no less importantly, the mosque of Ibn Tulun in Cairo (completed 879). The Alhambra’s ascent in nineteenth-century publication and design history is a well-known story that does not need to be repeated here.7 Instead, the first two sections of this chapter will pick up the trail of the Ibn Tulun mosque, tracking it as it appears and disappears like a fine thread running through the story of the nineteenth-century European encounter with the arabesque. The final section will turn to the fully commodified Islamic art object in the later nineteenth century.

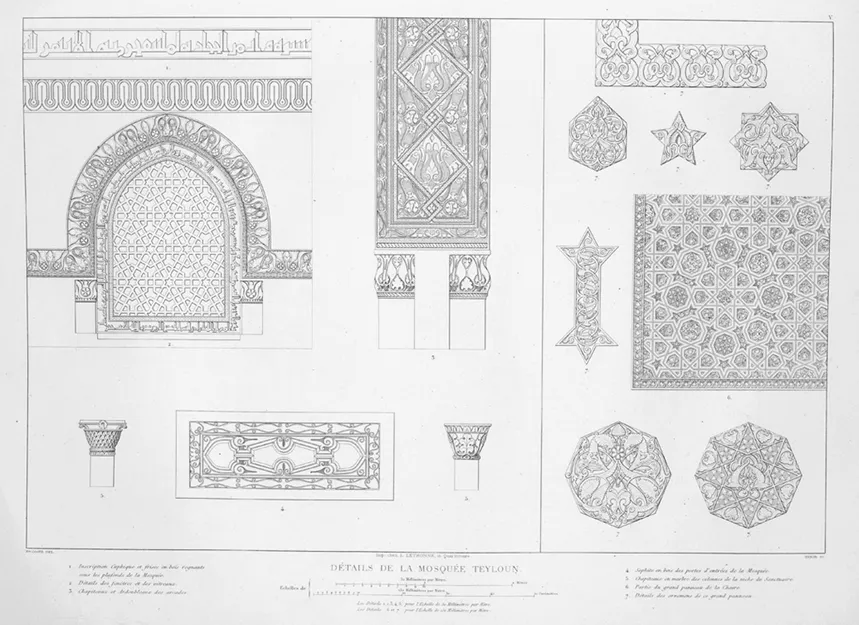

The circumstances of production for these lavish superbooks varied. Some were created by architects who had worked for imperial patrons, like Pascal-Xavier Coste (1787–1879), who published his celebrated Architecture arabe, ou monuments du Kaire (1837–1839) in Paris ten years after his return from service under the Egyptian regent Muhammad Ali (r. 1805–1848). Coste’s volume measures more than half a meter along its longest side. The 100 plates frame an extraordinary abundance of architectural information, from interior views in highly rationalized single-point perspective to ground plans, elevations, and details of applied design, all rendered in the precise lines of professional architectural draftsmanship.8 The carved stucco of the Ibn Tulun mosque, which has a special place in the historiography of the arabesque, makes an early appearance in Architecture arabe. While Coste’s working drawings from 1822 reveal some hesitation and labor in capturing the building’s stucco designs, the published plates present them boiled down into pure, linear design (Figure 1.1).9

Figure 1.1“Détails de la mosquée Teyloun.” Pascal-Xavier Coste, Architecture arabe, ou monuments du Kaire, mesurés et dessinés, de 1818 à 1826 (Paris: Firmin Didot Frères, 1837–1839), plate V.

Image courtesy of New York Public Library.

Yet this appearance of scientific objectivity in Coste’s plates is mi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half-Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- Preface and Acknowledgments

- Introduction: The Arabesque Aesthetic

- 1 Spatchcocking the Arabesque: Big Books, Industrial Design, and the Captivation of Islamic Art and Architecture

- 2 Poet, Artist, Arabesque: On Peter Cornelius’s Illustrations to Goethe’s Faust

- 3 The Lithographer’s Mark and the Magic of Synchrony

- 4 The Decorative Line of the Nabis: Expressivity and Mild Subversion

- 5 Ephemeral Arabesque Timbres and the Exotic Feminine

- 6 Arabesque in French Music after Debussy

- 7 Drawing a Line with the Body

- 8 About An Arabesque

- Index