- 56 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

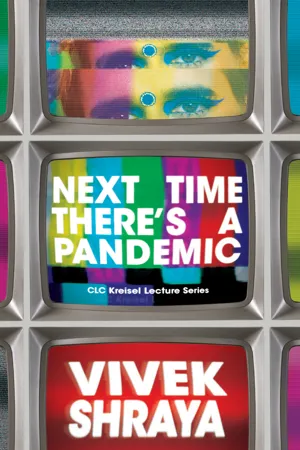

Next Time There's a Pandemic

About this book

"During my first post-lockdown massage, I willingly engaged in the requisite chit chat about lockdown experiences with my therapist. He gushed behind his mask: 'Oh man. It was so great. Every day I woke up, drank coffee, read, rode my bike…'

My therapist's description did sound pretty great. But it was nothing like my own anxiety-ridden ordeal…

Had I done the lockdown wrong?"

In Next Time There's a Pandemic, artist Vivek Shraya reflects on how she might have approached 2020 and the COVID-19 pandemic differently, and how challenging and changing pervasive expressions, attitudes, and behaviours might transform our experiences of life in—and after—the pandemic. What might happen if, rather than urging one another to "stay safe," we focused instead on being caring? What if, instead of striving to "make the best of it" by doing something, we sometimes chose to do nothing? With generosity, Shraya captures the dissonances of this moment, urging us to keep showing up for each other so we are better prepared for the next time...and for all times. Afterword by J.R. Carpenter.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Next Time There's a Pandemic by Vivek Shraya in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Literary Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

STAY CARING

AS THE NOVEL CORONAVIRUS SPREAD in early 2020, COVID-specific words and phrases like “PPE,” “social distancing,” and “flatten the curve” became ubiquitous. I personally hope I never hear the word “unprecedented” again. Another early phrase I found vexing was “stay safe.”

As a writer and English teacher, obsessing over and being critical about word choice is my job (don’t get me started on the biggest coronavirus plot twist: not so “novel” after all!), and yet I was initially unable to figure out why “stay safe” bothered me. It may seem finicky to harp on a well-intentioned phrase, but as our social interactions were reduced so drastically, this phrase was often the only message I would hear from anyone other than my boyfriend. The more I was urged to “stay safe,” the more aware I became that that safety isn’t something that everyone has access to or can choose. This awareness was acute especially because, ironically, I heard this phrase most frequently from grocery clerks and delivery people, some of the many workers who were forced to risk their health to survive and so that others could survive. Were they actually encouraging me to stay safe, or was this phrase a kind of mantra for themselves? Or were they (subconsciously) pleading with me to stay home to avoid endangering them?

The general interchangeable usage of “stay safe” and “stay home” also implied that home is a safe place, a haven for everyone. But the increase of domestic violence during COVID is a reminder that this assumption isn’t true. For people faced with this reality, “stay safe” is an ignorant and even callous directive.

Personally, I can try to stay as safe as I want, but as a trans feminine, queer, brown person, regardless of whether there is a global crisis, I can’t control how others react to me. Pre-pandemic, I approached any kind of outdoor activity, including walking, with a baseline of trepidation and alertness because of my past experiences of public harassment. I’m already used to walking on the edge of the sidewalk, or the grass, or even the road when other people are around, not because I was previously scared of catching a virus, but so that men behind me can pass, or rather so I’m never walking with a man directly behind me.

Perhaps related: I spotted a number of openly affectionate queer couples on my daily pandemic walks, an uncommon sight, and I wondered if queers felt safer to express themselves publicly with so many (straight) people forced to be indoors.

Next time there’s a pandemic, I hope that whatever “slogan” we use is less about individual responsibility, like “stay safe” or even “take care,” and more about collective care and action, like “stay caring” or “stay kind.” More importantly, I hope we will consider how we can provide collective care, especially when physical contact with others is restricted.

For me, this meant thinking beyond the sanctioned contact of biological family and romantic partners. I made a conscious effort to centre those in my life who had the least support—my single women friends—by phoning them regularly or sending them gift cards for essential goods and services. Similarly, friends sent me care packages and flowers, and some also dropped off baked goods. Some of us had transparent conversations about the challenge of wanting to check in regularly while understanding how impossible it felt at times to come up with an adequate response to “How are you?” One solution was to send each other daily heart emojis to communicate caring and as “proof of life.”

I also tried to remember those outside my social circles and by supporting local businesses, donating to community organizations, like women’s shelters, and contacting members of Parliament to lobby for wage increases for frontline workers.

But as I navigated my own mental health, most of my efforts were sporadic at best, and seldom felt adequate.

SKIP THE GRATITUDE AND SAY WHAT YOU FEEL

THROUGHOUT 2020, I also heard many versions of the comment that only those who are willing to adapt will endure. These comments were directed not just toward business owners and arts administrators but also at individuals. The subtext: survival of the fittest.

The problem with survival of the fittest is that it glorifies individual strength while refusing to acknowledge the factors that enable some individuals to be “stronger” than others. Quarantining with my white, straight-passing boyfriend, I was constantly reminded of my lack of emotional strength. He commented early in the pandemic that he could likely quarantine for months and months and be fine. Even be content. And he truly did seem unphased by the chaos, peacefully watching movies and playing video games while I paced around our place or forced myself to write or read (but my eyes refusing to lock into any of the words).

Witnessing his apparent “adaptation,” I wondered what was wrong with me. What was my problem? Why couldn’t I figure the pandemic out (because it was a puzzle, right?)? Why couldn’t I settle into a stable and productive routine even after months had passed? I had a stable income, a beautiful apartment, supportive friends. I was not in immediate danger but I still felt on edge.

It took me awhile to realize that this unease stemmed from the reality that, despite the repeated insistence that “we’re all in this together,” we all didn’t enter the pandemic equally. The panic of the lockdown exacerbated the physical and mental effects of my previous experiences of trauma and oppression. Every night I dreamt of being hunted or killed, or I had unimaginative stress dreams about arriving late (and pantless) on the first day of class. When I was awake, my inability to exert control over my life, which is one of my primary survival mechanisms, left me in freefall, endlessly worrying about the end of my art career, as dozens of my gigs were instantly cancelled, and about being fired from my teaching job, as the institution where I work (and am the newest department hire) continued to announce drastic budget cuts. I also worried because my chronic pain is triggered by computer work, so I was unable to transition to online teaching without causing further physical harm and I didn’t know what impact this would have on my job security. Or rather, what would it take for me to feel secure, when being trans (and racialized) is associated with unemployment? Any security I have acquired has always been anomalous, not the norm, for someone like me. In contrast, my white colleagues (thankfully) reassured me multiple times that our jobs were safe. I wondered what it would be like to possess that kind of certainty and conviction in the midst of precarity. Is it surprising, then, that a white man can quarantine and be content compared to those of us whose identities are more stringently tied to familial and social responsibilities or whose experiences have taught us the necessity of living in a state of constant anticipation of danger?

As someone who struggles to manage the effects oppression has on my mental health, I have a finely tuned system that keeps me afloat. I routinely work out to expend my excess anxiety. I go out to see m...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copright

- Dedication

- Foreword

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- Introduction

- 1 Stay Caring

- 2 Skip the Gratitude and Say What You Feel

- 3 Nothing is Better than Something

- 4 Value Artists

- 5 Less Surveillance, Less Judgement, More Grace

- Afterword

- Acknowledgements

- About the Author

- Clc Kreisel Lecture Series