![]()

CHAPTER 1

THE NIAGARA ESCARPMENT

Ontario: a province, a lake, a county. Properly it should be On-tar-ack or Onda-rack. On means “high,” tarack, “rocks”; that is, “rocks standing high in or near the water,” The reference is probably to the Niagara Escarpment.1

William F. Moore, 1930

To the casual observer, southern Ontario is boring and flat. The fact that this “flatness” is actually a complex mosaic of hills and valleys is of little consequence to most people (outside the cycling community!). The truth is that these hills and valleys have never inspired the same passion among writers and artists as, for example, the Rocky Mountains or the Appalachians, both impressive on a massive scale. These geological masterpieces demand attention and command respect. They have transcended the relative boredom of their surrounding landscapes and we, too, are impressed with them. Southern Ontario, on the other hand, has been little more than a dumping ground for massive glaciers that intermittently ploughed their way across the northern half of the continent. When climate warmed, they shrank northwards. The glaciers weren’t particularly neat about it, either. Think of a roadside after snowmelt in the spring. Debris churned up by scouring was dumped everywhere. The continental glaciers were undoubtedly an impressive sight (imagine an ice wall over a kilometre thick!), but the slurry they left behind, considerably less so.

As rivers and streams dissected the landscape and plants and animals recolonized the surface, southern Ontario developed its character. Many of the bumps and hollows that dot the landscape tell a fascinating story, but it is the Niagara Escarpment that is its showpiece – the showy orchid amongst the clover. Take your friends or family down one of many Escarpment back roads and watch how everybody strains for a view of the cliff face. It isn’t surprising that a visual encounter with the Escarpment is treated with such fanfare. It is as if humans need rock – we like to see mountains, outcrops and cliffs. They comfort us. We appreciate their aesthetics even if we don’t know why. If located elsewhere, the Niagara Escarpment might be overshadowed by more impressive topography, but here in southern Ontario it is a visual vertical refuge from the horizontal glacial landscape. It cuts its way from the Niagara Peninsula in the south to the Bruce Peninsula in the north, stretching onto the islands off Tobermory. From there it continues onto Manitoulin Island. Luckily, it provides a natural corridor for plant and animal life, while acting as a natural barrier to human traffic. Much of the land along the Escarpment is relatively undisturbed because it was such an obstacle to the expansion of Europeans in southern Ontario.

The real story of the Niagara Escarpment actually begins over 400 million years ago when North America looked very different than it does today. This was during the period in geological history known as the Silurian. An inland sea covered the interior of the continent during this time in an area now known as the Michigan Basin. Large numbers of dead marine invertebrates and sediments accumulated at the bottom of this sea. These sediments would eventually form the dolomitic caprock that we now see on the Niagara Escarpment. For 130 million years, the land remained underwater and layer upon layer of sediments and organisms accumulated on top of the Silurian deposits. The tremendous weight of these overlying layers exposed the underlying deposits to intense pressures that chemically transformed the sediment/invertebrate mix into rock.

If the Silurian dolomites mark the upper layers of the Escarpment cliff face, what happened to everything else deposited over the last 400 million years? In short, there is no way of knowing. Clearly, the rock and/or sediments that had accumulated here have eroded away. Much of this erosion likely occurred soon after the disappearance of the inland sea and the development of drainage basins on the emergent land. Surface water then removed the overlying sediment. Undoubtedly, some layers of sedimentary rocks did form after the Silurian, but they have now disappeared.

The Niagara Escarpment was formed from sediments and the bodies of invertebrates that accumulated at the bottom of a large inland sea nearly 400 million years ago.

The Niagara Escarpment has probably existed as a landform for millions of years. Once the overlying deposits were removed, the dolomite and limestone resisted erosion more so than the underlying shale. It is likely that the Escarpment has been exposed as a series of rock outcrops or cliffs ever since. Versions of Ontario’s Niagara Escarpment that predate the last glaciation formed several kilometres north and east of its present-day location. The cliffs of this early Escarpment were also considerably lower than the present-day cliffs because the caprock layers were thinner. Since the stratigraphic layers of rock dip south – to westward towards the centre of the Michigan Basin, the exposed rock surface faces approximately north to east. Erosion at the surface, facilitated by down-cutting from streams, moved the cliff in the direction of the dip thus exposing more tough Silurian dolomite and limestone. The cliff grew in height as it migrated.

Like most of Canada, the story of the Niagara Escarpment is primarily a story about the constructive and destructive powers of ice. Glacial lobes2 moved through southern Ontario several times; the most recent or Wisconsinan stage was effective at redistributing the handiwork of its predecessors. Deep sea sediment cores indicate that as many as twenty glacial episodes have affected North America over the last two to three million years. Although we know very little about the earliest glacial advances, we do know that the current landscape of southern Ontario is still primarily a product of the Wisconsinan glaciers. Like a giant Etch-a-Sketch, the Wisconsinan glaciers picked up everything in their paths, and shook them all around. Considering the thickness of the ice over the Escarpment, the landscape would have provided little resistance to the advancing sheets. The ice created a new baseline upon which other physical and ecological processes could act.

Two types of landscapes emerged from beneath the mountains of ice; one formed by deposition, the other by erosion. The land was either a sink or a source for the large volumes of glacial debris moved through the region. Evidence of glacial scouring can still be observed on the bedrock. Glacial meltwater streams cut through the Escarpment, while others cascaded over the cliffs to form incised valleys downstream. Some cliffs were separated from the main Escarpment and formed circular outliers (those sections of the Escarpment that are separated from the main cliff face) that are still evident at places like Cape Croker, Rattlesnake Point and Mono Cliffs. Some exposed bedrock was buried by unconsolidated glacial deposits or till. Till is carried by the glaciers and laid down when they stall or melt in situ. While the exposed dolomite of the Niagara Escarpment resisted the erosive powers of the glaciers, in some regions, such as Dufferin County, the exposed bedrock was buried by till and exposed cliff faces are virtually absent.

The Niagara Escarpment emerged as a bedrock feature from beneath the Wisconsinan Ice Sheet after the first ice-free areas were exposed close to 13,000 years ago. Within a thousand years, the ice sheet lay just north of Manitoulin Island. The meltwater was channelled east and water levels in the Great Lakes basin were relatively low. Most of the northern Escarpment, however, remained under the waters of glacial Lake Algonquin. The depressed land had yet to recover from the weight of thousands of years of overlying ice. In some areas, the meltwater removed (in some cases catastrophically) overlying glacial drift and exposed the rock below. Eventually the land rebounded as water levels dropped and subsequently exposed areas of the Niagara Escarpment that were previously underwater. Variable rates of inflow from the north, coupled with variations in the direction and speed at which water could be drained into the St. Lawrence River, led to wild fluctuations in Great Lakes water levels over the next few thousand years. During these times, sections of the Escarpment were repeatedly exposed and inundated with water. The elevated middle portions of the Escarpment were least affected, but on the Bruce Peninsula the last flooding event occurred only 7,000 years ago. Lake levels continued to fluctuate (and continue to fluctuate today), but by 3,500 years ago, the peninsula looked very similar to the landform that we see today.

A large plain separates the cliffs of Mount Nemo [shown here) from Rattlesnake Point, near Milton, Ontario,

The Escarpment itself has been doing battle with a broad suite of physical forces over the last 15,000 years. Initially, glacial erosion removed overlying bedrock exposing grey and blue-grey dolomitic limestones and dolostones. Most of the original steepening of the exposed bedrock resulted from direct contact with glacial ice. Large influxes of cold glacial meltwater into the Great Lakes Basin prevented the climate from warming too rapidly. The discovery of periglacial features such as protalus ramparts indicate that permanent snow packs persisted for hundreds of years along the base of the cliffs. These ramparts, or slopes, developed at the bottom of talus slopes and formed when rockfall hit the snow or ice. The debris rolled downslope and accumulated as a steep, rocky ridge. Meltwater channels also shaped cliff faces by cutting through them and creating a series of waterfalls, bedrock outliers and incised valleys. Drastic changes in postglacial lake levels completely inundated some faces, only to expose them again hundreds of years later. Wave-cut stacks or flowerpots, archways, sea caves and undercut cliffs were created where water interacted directly with the cliff face.

The effects of wave action have separated this stack or flowerpot from the Escarpment on Flowerpot Island.

It has been argued that the Niagara Escarpment talus may be a relict feature that developed shortly following deglaciation. Most undercut Escarpment cliffs were created by glacial ice, wave erosion at the cliff base or increased freeze-thaw activity brought on by severe climatic conditions at the end of the last glacial advance. Therefore, most of the talus formed 10,000 to 15,000 years ago. Undercutting has been minimal over the last few thousand years. Frost does not penetrate more than four centimetres into the cliff face under present climatic conditions, which is unlikely to account for the large boulders that lie in the talus below many cliffs. One section of cliff face around Barrow Bay has previously been described as unstable because it has a high proportion of freshly fractured rock in the talus and there are several large, steep talus cones at the cliff base. However, the oldest living tree along the entire Niagara Escarpment is rooted under a huge overhang at this site! We are not implying that significant rock fall events do not occur along the Niagara Escarpment. We have seen the evidence for recent rock fall at several cliffs including Halfway Log Dump, Purple Valley and Rattlesnake Point, but as an entity, the Niagara Escarpment is not a naturally unstable feature of the landscape anymore.

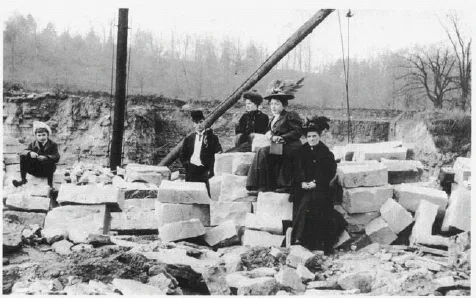

A limestone quarry used for the production of cut Stone. Courtesy of the Esquesing Historical Society.

The last one hundred years in the Escarpment’s history, however, has brought about noticeable change. At first the European expansion into southern Ontario had little influence on the Escarpment, and it persisted on the landscape as it had for thousands of years. Even while the rest of the Ontario’s natural landscape was being dismantled, the ancient cliff forest flourished. The construction boom that accompanied the migration of Canada’s populace off farms and into urban centres, however, increased the demand for limestone as a natural resource. Limestone was cut for building stone and many of the oldest stone buildings in southern Ontario were built from Niagara Escarpment limestone – from turn-of-the century farmhouses to townhouses and homes in neighbouring cities such as Hamilton and Toronto.

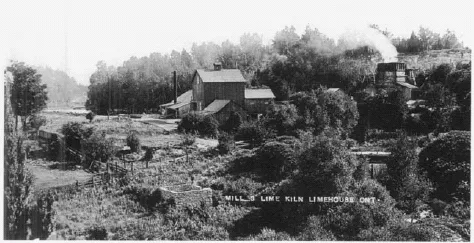

Lime was once in heavy demand for building construction and limestone was quarried at several locations along the Niagara. This mill and lime kiln operation was located near Limehouse. Courtesy of the Esquesing Historical Society.

Lime, a basic ingredient in mortar and plaster, was also heavily in demand. In the 1880s, every new stone or brick home contained large amounts of lime, which was produced by burning limestone at high temperatures. Quarries along the Niagara Escarpment extracted the rock that fuelled this boom. The cliff was broken into sections known as benches, using dynamite placed inside holes drilled into the rock. The benches were then broken into smaller pieces by men wielding sledge hammers. Two-wheeled horse-drawn carts hauled the limestone to open lime kilns fed by wood fuel twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, to reach temperatures surpassing 1800°F. Thirty-six hours later, the “draw” of lime was loaded directly into “tips” or railcars. The lime was weighed, cooled and loaded into boxcars for transportation. By the mid-20th century,...