![]()

CHAPTER ONE

“That Sweet Comfit Men Call Sugar”

The beginnings of sugar are generally believed to have been centred in the islands of the South Pacific. In the ancient mythology of the Solomon Islands, sugar cane is credited with the birth of mankind, with the original male and female sprouting from the ripened stalk of a cane. In a similar story from New Britain, two fishermen, To-Kabwana and To-Karvuvu (“To” being the Polynesian for sugar cane) found a piece of cane trapped in their nets. They planted the cane stalk, which grew and brought forth a woman. During the day, she cooked and cared for the men and at night hid herself within the cane. Discovering her nightly secret resting place, the men forced her to remain with them. Eventually she became wife to one of the fishermen and from their union sprang the whole human race.

More prosaically the earliest recorded use of cane for food is found from about 500 B.C. in certain holy scriptures in India, where it was generally used as a vegetable, with the body of the plant being boiled into a pulp. The earliest datable mention of sugar cane comes from 325 B.C., when sugar (and sugar cane, by inference) is recorded by the Macedonian General Nearchus, during his campaigns in the east under Alexander the Great. From the very beginning, efforts were made to produce a distinct concentrate from the cane juice, resulting in the production of the roughest or crudest type of sugar known as Jaggery or Gur.

From the time of the empires of Greece, and later Rome, there are a number of accounts that indicate a knowledge of the existence of sugar cane and its sweet extract. They include Erathosthenes (c 276 - 194 B.C.)

The roots of plants [in India], particularly of the great reeds are sweet by nature and decoction.1

and from Seneca the Younger (3 B.C. - 65 A.D.),

They say that in India honey has been found on the leaves of certain reeds [produced] by the juice of the reed itself, which has an unusual richness and sweetness.2

Unfortunately, recorded documentation is somewhat less clear about the extent of sugar usage within the average Greek or Roman home, and it is generally thought that honey remained the principal sweetener in those times.

The real credit for the spreading of sugar cane cultivation must go to the Arabs. During their great period of conquests throughout the Mediterranean basin in the latter half of the first millennium A.D., the Arabs discovered or, perhaps more accurately, were introduced to sugar by the Persians around 600 A.D., and readily assimilated it into their own culture. In turn, they introduced the cultivation of sugar cane to most of their later conquests. Records of the various ruling governors of conquered states indicate the growing of sugar cane in such diverse places as Syria (circa 640 A.D.), Spain (650 A.D.), Palestine (650 A.D.), Egypt (650 A.D.), Sicily (655 A.D.), Cyprus (655 A.D.), Morocco (682 A.D.), Crete (823 A.D.), and Malta (870 A.D.) By the year 1000 A.D., the humble sugar cane had become an economic crop grown throughout the length of the Mediterranean and the Near and Middle East. This widespread use within these countries now led to the next phase of sugar’s history - its introduction to the cultures of Northern Europe. For these populations, the only sweetener readily available prior to 1000 A.D. was honey, and most of the royal courts and major religious houses had specialists on staff to keep the beehives and provide honey to the kitchens.

The wave of Islamic conquests brought the counter-reaction of the Christian world for a crusade to retrieve the holy places. With the successive series of invasions of Moslem strongholds by the Crusaders, sugar came to the attention of Western scholars, prompting Fulcherius Carnotensis to write in the early eleventh century: “On the fields of Laodicia [Turkey] we found certain reed like plants called cannamella [reed-honey]”3 while Jacobus de Vitriaco wrote the following about the Jordan valley:

There is a reed from which flows a very sweet juice called cannamelli zachariae, this honey they [the Arabs] eat with bread and melt it with water, and think it more wholesome than the honey of bees … with the juice of this reed our men at the siege of Acre often stayed their hunger.4

Quick to appreciate the value of this new sweetener, the returning Crusaders not only disseminated the information about the existence of sugar cane, they also brought back samples of cane and semi-processed sugar, much to the delight of those at home. Meanwhile, in the Holy Land itself, groups of Crusaders formed merchant cartels in order to gain control over the sources of production, which they maintained for the following two centuries (thus funding their other, more martial activities). Following the loss of the Holy Land to the Saracens in the late thirteenth century, the centre of sugar cane cultivation gravitated westward through Cyprus, Sicily, and Spain, until by the early fifteenth century the islands of Madeira, Tenerife, and other parts of the Canary group of islands were the major production centres for sugar cane. Meanwhile, within Europe, the introduction of sugar for consumption had wrought some significant social and economic changes.

It may be of some surprise to the modern reader that while today we think of “sugar and spice” as counterpoints in our taste range, to the medieval mind sugar was a spice, alongside pepper, nutmeg, ginger, and coriander. Numerous dishes using beef, pork, poultry, and fish were seasoned with combinations of sharp-flavoured spices and sugar, or used sugar-based sauces, but the price of sugar placed its use well beyond the means of any but the most wealthy. In the official records of royal houses such as that of Henry II of England (1154 - 89), we first see the regular purchase of sugar for use in the royal kitchens. By the year 1243, Henry III of England was ordering 300 pounds of “Zucre de Roche” and by 1289 records indicate that the royal household of Edward I consumed more than 6,258 pounds of sugar per year. Expensive as it was, this royal example of sugar consumption was enough to ensure rapid mimicry by the nobility. Throughout the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, household accounts clearly indicate that in the upper echelons of society, sugar had become a status symbol. It was given as a gift alongside precious metals and spices, or blended with marzipan, oil of almonds, rice, and various gums to create a form of edible clay, from which artistic masterpieces could be created. These sugar sculptures were called “subtleties” and were generally served between major courses, taking the forms of real and fantastic beasts, buildings, heraldic designs, and famous warriors. Entire festive tables would be covered with subtleties and the intense political and social rivalries between the noble houses (coupled with the example of the royal households) led to a profligacy of sugar use that would horrify the modern accountant. At the same time, sugar began to be used extensively as a pharmaceutical product and was touted as the wonder drug of the age. It was claimed that sugar was capable of curing haemorrhoids, stomach ulcers, headaches, and childbirth pain, and by the late fifteenth century the use of sugar in medicine was so well established that a saying “like an apothecary without sugar” meant being totally useless. One quotation from the writer Tabernaemontanus (c1515 - 1590) gives an idea of the feelings towards sugar at that time and indicates that not all “modern” ideas are necessarily new.

Nice white sugar from Madeira or the Canaries, when taken moderately cleans the blood, strengthens body and mind, especially chest, lungs and throat, but it is bad … for hot and bilious people for it easily turns into bile, makes the teeth blunt and makes them decay. As a powder it is good for the eyes, as a smoke it is good for the common cold, as flour sprinkled on wounds it heals them … sugar wine with cinnamon gives vigour to old people.5

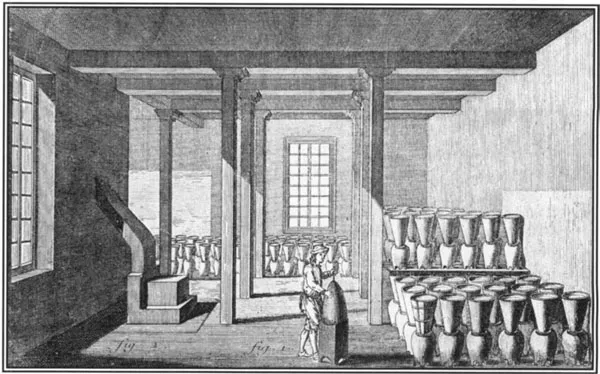

Inside the workshop of a medieval apothecary, showing the sugar cones on the shelves.

The mention of “nice white sugar” is of particular note since it clearly indicates that by this time sugar refining was well established as an industry in its own right. Although it is known that various degrees of cleaning and concentration of sugar took place simultaneously with the spread of the growing of sugar, refining did not really develop into an industry until the mid-fifteenth century. When some of the major merchant families of Venice acquired the knowledge of refining by the use of conical drainage moulds, the “sugar cone” had arrived. Huge incomes were generated for the refining “families” by their sugar “houses,” their sales network covering all of Western Europe. Such was the economic and strategic value of this new technology that local laws were passed forbidding, upon pain of death, the exportation of production machinery, technological information, or even trained personnel to other regions. However, as in most such cases, the desire for knowledge and profit outran the legal restrictions. Soon additional refining operations sprang up across Europe. By the mid-sixteenth century, there were more than thirteen refineries in Antwerp alone, with additional production centres in Amsterdam, Augsburg, Bordeaux, Lisbon, Bristol, and London. The technology of this period (i.e., the use of sugar cone moulds and “claying”*) appears to our modern eyes as slow, crude and inefficient. But in terms of the technology of the time, it represented a quantum leap in the production capabilities of the sugar manufacturers. These advances reduced costs and allowed prices to fall, making sugar an even more attractive product - which was just as well, since the wealthy, middle and upper classes had been demanding, in increasing volume, access to the sweet luxury previously enjoyed only by royalty. Furthermore, such was the success of this technology in producing the desired product that from the sixteenth century to the mid-eighteenth century, the art of refining by the sugar cone method changed very little. But in terms of the mainstream history of sugar, our attention must now span the Atlantic with the discovery and development of the New World as the centre for sugar production.

The fill-bouse of an eighteenth century sugar house, illustrating the rows of sugar cones undergoing refining.

Documentary evidence indicates that it was Christopher Columbus who brought sugar cane to the Americas on his second voyage in October 1493 and that he was significantly impressed by the rapidity with which the transplanted sugar cane germinated and grew. The economic bonanza that sugar production represented to the expansionist powers of Britain, France, Spain, and Portugal led to a race for the establishment of colonies throughout the Caribbean Islands, as well as the adjacent coasts of South, Central, and North America. The competition was so fierce that local raids between ships and garrisons of the various powers in the Caribbean escalated into full-scale wars on the European mainland. Entire governmental policies were based on the economic control (and subsequent revenues) that could be derived from the growing and production of sugar. By 1680, the English had succeeded in occupying the Leeward Islands, Barbados, Jamaica, Antigua, Grenada, and Trinidad. Spain held onto Cuba, Porta Rico (Puerto Rico), and Hispaniola (Haiti and the Dominican Republic), as well as mainland colonies. Portugal controlled Brazil and areas of Central America. The French had Martinique and Guadeloupe (having lost most of their original territories to the English), while the Dutch were clinging to their toehold in the New World around their Guiana’s colonies. The individual histories of these areas during the next two hundred years is a fascinating story of political and economic intrigue. Unfortunately there is not space here to chronicle that tale. Suffice it to say that fabulous fortunes were made and lost by plantation owners and traders.

As in most cases where there is a rapid production of wealth for a minority, there is a negative impact on the majority, which in this case related to the vast amounts of labour required for the sugar cane fields and mills. Initially some labour was derived from indentured whites and local Carib natives. But as time progressed, the use of imported black African labour came to dominate the workforce, and the “Black Triangle” trade route developed. Under this system, finished goods were loaded into ships in northern European ports and were then shipped to the African slaving centres run by Muhammedan Arabs and coastal black natives, who were eager to exchange captured negroes of the continental interior for the trade goods. The chained and branded slaves were forced aboard the ships and chained to makeshift platforms, with the absolute minimum of space between either individuals or racks of more slaves above and below. During the subsequent voyage t...