CHAPTER 1

Professor Alois Alzheimer:

A Scientist with Heart

Born on June 14, 1864, in the small Bavarian town of Marktbreit, in Germany, Aloysius or Alois Alzheimer was the second son of royal notary Eduard Alzheimer. His birth went smoothly and he was baptized two weeks later, according to the Catholic rite of the time, in his father’s house. Restored in 1995 by the Eli Lilly pharmaceutical company, the house has since been turned into a museum and a renowned international conference centre.

Little Alois had a carefree childhood. He attended his neighbourhood school until 1874, the year his father decided to send him to live with his uncle in Aschaffenburg, where he would continue his studies at that town’s school. After Alois’s birth, five other brothers and sisters were born into the family. Needing more space, the whole family eventually decided to join his father’s older brother in Aschaffenburg.

In 1883 Alois graduated from high school. His professors noted in their written report: “This candidate has demonstrated exceptional knowledge in the natural sciences, which he showed a particular preference for during his years at school.” He lost his mother shortly before finishing high school. His father later remarried and had one more child.

Concern for their fellow human beings was a tradition in the Alzheimer family and led several members to go into teaching or the priesthood. Alois saw an opportunity in the medical profession to combine his personal interests in the natural sciences and human relations, a passion that drove his life until his death at fifty-one. Although his older brother had suggested he join him in the university city of Würzburg, Alois decided to undertake his university medical studies in Berlin.

The city of Würzburg today.

He officially entered the Faculty of Medicine at Royal Friedrich Wilhelm University in the autumn of 1883. Professor Waldeyer’s anatomy courses fascinated him. The renowned pathologist had published a ground-breaking scientific article on the development of cancer, an article that challenged the established dogmas of the day. Interestingly, this work still forms the basis of several different avenues of research examining the spread of cancers in the human body. Alzheimer continued his studies the following year in the city of Würzburg, where he felt closer to home. There he discovered fencing, a sport he played with great enthusiasm until the day he received a fairly serious facial wound that left him with a deep scar — this wound was the reason Alzheimer nearly always refused to be photographed from the right side.

In the winter of 1886, Alzheimer left the University of Würzburg to do a more advanced internship at the University of Tübingen. As a young man, his considerable height (1.8 metres) gave him a physically powerful look and earned him a certain degree of respect from the other students. Some twenty years later, Alzheimer would return to this very university to give an intriguing and historical lecture on a “new disease of the cerebral cortex” at a German medical conference.

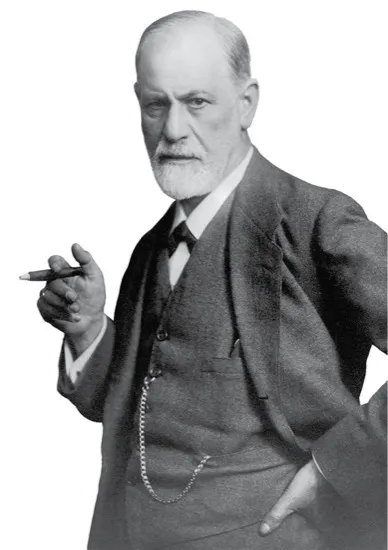

Finally, in May 1888, Alzheimer passed the examinations of the Würzburg Medical Examination Board with first-class honours. That same year, Sigmund Freud presented the rudiments of what would later become psychoanalysis, a new branch of medicine arguing for the novel concept of healing through words. Meanwhile, Alzheimer introduced the use of the microscope in psychiatry, but frequently insisted on having private conversations with his patients. It was at this time that he began seriously asking questions about the biological roots of so-called “mental” illnesses.

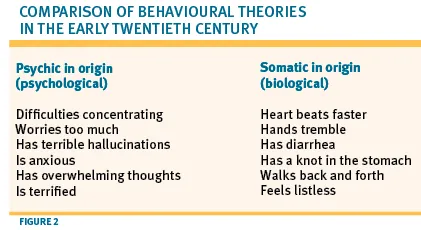

In the period when Alzheimer was beginning his career as a physician and psychiatrist, two entirely different philosophies were at odds with each other to explain the origin of mental illnesses. Members of the first group, known as “psychists,” were convinced that these illnesses were purely psychological in origin and could therefore be treated only by manipulating thoughts.

Professor Sigmund Freud, 1922.

The “somatics,” on the other hand, believed that disorders affecting the mentally ill were organic or biological in origin. These two diametrically opposed views often came into conflict at scientific or medical gatherings. Thus, physicians like Alzheimer, who were interested in biological and pathological changes in their patients, were generally poorly regarded among “psychists” like Freud.

It was in this very particular context that young doctor Alois Alzheimer, then twenty-four, left Würzburg to join the medical team at the Frankfurt am Main psychiatric hospital (Verhey, 2009). Called the “lunatics’ castle” by the local population, this psychiatric hospital was one of the largest complexes of its kind in Germany. Built in gothic style, and without the traditional high walls of psychiatric institutions of the period, it stood outside the city of Frankfurt. A year later, a young doctor named Franz Nissl joined Alzheimer’s team. There was a desperate lack of staff in the huge complex, which usually only accepted the most serious cases of mental illness. Today, Nissl is recognized as one of the pioneers in cerebral microscopy and one of the most enthusiastic defenders of the theory that mental illnesses are biological in origin. The two young doctors, under the kindly authority of Dr. Emil Sioli, undertook to completely change the way care was provided to patients by putting into practice the so-called “no-constraints” approach (Engstrom, 2007). The coercive methods then in use were gradually dropped, replaced by greater and more responsible freedom of movement.

A patient incarcerated in the Bethlem Royal Psychiatric Hospital, known as Bedlam, in London, c. 1800.

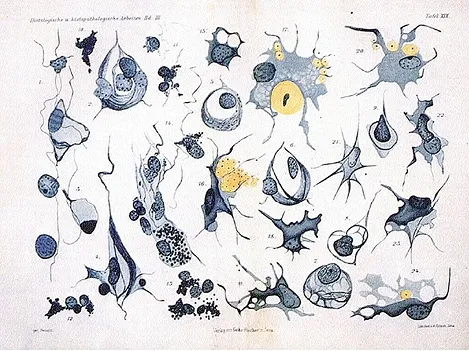

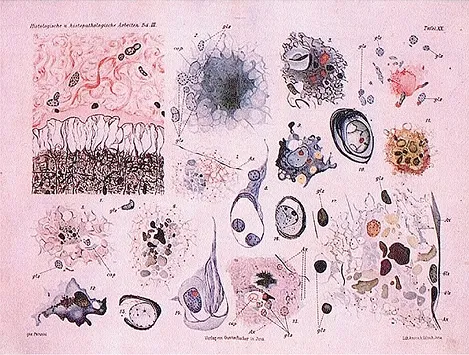

In the following years, Alzheimer first took an interest in psychoses that were biological in origin, often resulting in the active degeneration of blood vessels or the brain. Later, when he applied his scientific research in Munich, he became interested in “endogenous” psychoses, such as schizophrenia, manic depression, and the group of what are known as “early-onset” dementias. Thanks to his friend and colleague Nissl, who taught him cerebral histopathology techniques, Alzheimer was quick to make a link between the symptoms of patients he saw on a daily basis and microscopic analyses of the brains of patients who had died of these same illnesses.

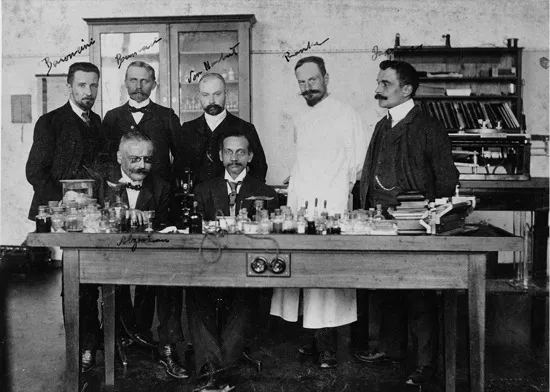

A group of psychiatrists, including Professor Alzheimer (seated on the left), in the University of Munich hospital, c. 1905.

The Case of Auguste Deter

Despite his departure from Frankfurt for Munich in 1903, Alzheimer had not forgotten the strange patient he had met for the first time in November 1901 (Verhey, 2009). At the time, Alzheimer was head physician at Frankfurt’s psychiatric hospital. His assistant, Dr. Nitsch, had examined a new fifty-one-year-old patient on her arrival at the hospital. He had decided to talk about her specific case with his supervisor, suspecting a very odd abnormality. Alzheimer had agreed to go and see the patient, a meeting that would completely change the direction of the rest of his career.

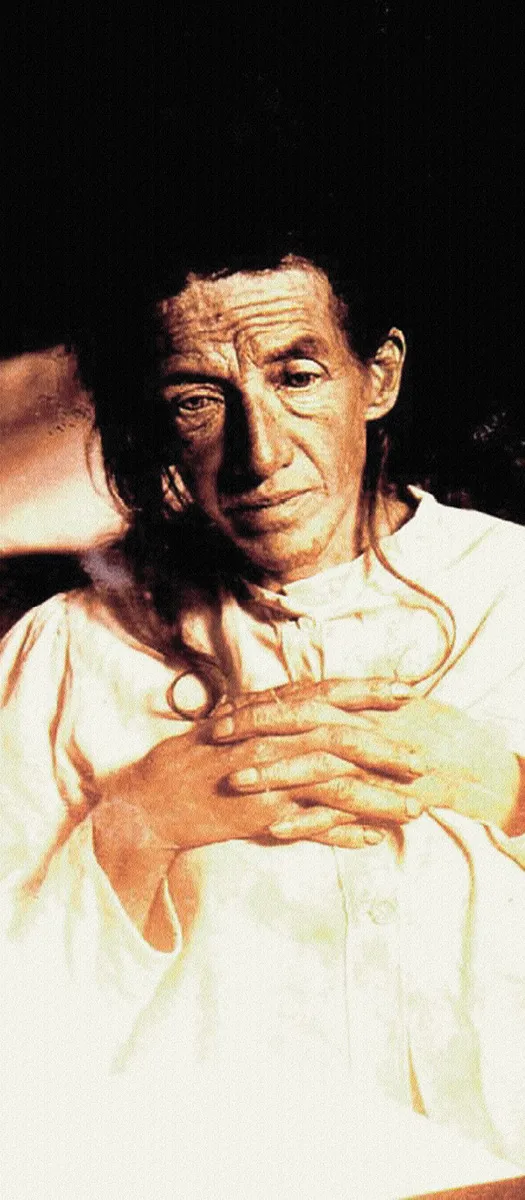

Right from their first conversations, Alzheimer became deeply fascinated by the patient, whose mood shifted constantly back and forth between gloom and contentment. She remembered her name very well, but had forgotten what year she was born. She was fully aware that she had a daughter living very nearby who had been married several years earlier in Berlin.

However, when Alzheimer asked her what her husband’s name was, she could not remember. Nor did she know what hospital she was in or how long she had been there. On this surprising note Alzheimer’s investigations began; he had already seen a few patients with similar traits, although none displaying so many inconsistencies all at once (Maurer et al., 1997). A general examination indicated this was a person in good health. A neurological examination appeared normal, aside from a few minor abnormalities. Periods of lucidity quickly gave way to incoherent and sometimes even aggressive behaviour. The patient frequently appeared anxious and sometimes very distrustful.

Auguste Deter’s case fascinated Dr. Alzheimer. He remembered having observed, in previous years, cases of dementia that he had referred to at the time as cases of senility, since the subjects were much older than Auguste Deter, who was in her very early fifties. In 1885, the examination of one of these patients had revealed a significant loss of neuronal cells in the brain and lymph glands, even when there was absolutely no blockage of the cerebral blood vessels. The doctor’s notes show that he suspected a hereditary weakness of the central nervous system to be at the root of the decrease in brain cells.

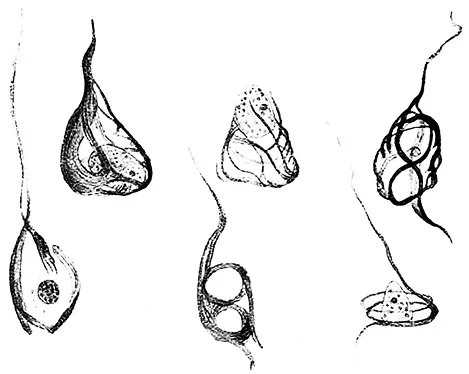

Neurofibrillary tangles from Auguste Deter’s brain drawn

by Professor Alzheimer (top and centre); plaques from

Auguste Deter’s brain (bottom).

Auguste Deter’s husband had told the doctors that she had always enjoyed very good health and had never had any serious infectious diseases. She did not drink and he felt she was very hard-working. He had stressed that until 1901 his wife had never shown any particular symptoms. Then suddenly, that autumn, she had begun to experience memory lapses and frequently lied to cover up some of her “absences” (Maurer et al., 1997). A few weeks later, she began to have trouble preparing meals and had sometimes begun to wander aimlessly around the apartment. Shortly before being hospitalized, she had started to hide all kinds of objects, plunging the apartment into a state of chaos that did not make any sense at all to her husband.

The preferred treatment prescribed by Alzheimer at the time consisted of taking lukewarm baths. He received encouraging results by recommending a rest in the afternoon and a light meal in the evening. Tea and coffee were forbidden. Sleeping pills were only administered when absolutely necessary. But, a year after being hospitalized, Auguste Deter became constantly agitated and very anxious. At night, she frequently got out of bed and disturbed the other patients. Communication with the patient became extremely difficult and not very productive. In the final note on the file written by Alzheimer himself, he noted that the patient had become violent when he tried to listen to her chest. She cried for no reason and had almost stopped eating.

Auguste Deter, the first patient diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

The stages of the disease as they are described here by Dr. Alzheimer are fairly typical of the normal progression of subjects with the disease that today bears his name. In his day, managing the patient’s symptoms was difficult, not to say primitive, from some points of view. Fortunately, the situation has changed greatly since then. The variety of treatments available to people with the disease today make possible better management of the symptoms, as well as the behavioural problems that arise later on in the course of the disease. We will discuss treatment again in greater detail in later chapters of this book.

In April 1906, in Frankfurt, Alzheimer learned of Auguste Deter’s death. He immediately asked his former mentor, Dr. Emil Sioli, to send him the patient’s medical file and, if possible, ...