![]()

PART I

The Secret

‘Tis the sunset of life gives me mystical lore,

And coming events cast their shadows before.

Thomas Campbell,

Lockiel’s Warning

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Prelude to Disaster

The Pobble who has no toes

Had once as many as we;

When they said, “Some day you may lose them all”; –

He replied, – “Fish fiddle de-dee!”

Edward Lear,

The Pobble Who Has No Toes

THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE

We will begin with a hypothesis. It is a very strange hypothesis but a fundamental one to our story. Therefore, we must lead into it gradually.

Ostensibly, the purpose of the Franklin expedition was to discover the Northwest Passage. This passage had been sought for hundreds of years dating back to Columbus’ famed voyage in 1492. Contrary to myth, no one in Columbus’ day thought the world was flat. They did, however, think it was about three times larger than Columbus believed it to be. And they were right. Both he and his crew would have perished at sea, their fate unknown, had they not run up against an unexpected land barrier and “discovered” the New World.

While Columbus was pleased with his discovery, to those who came after him North and South America meant only one thing — a very large obstacle on the way to the Spice lands of the East. For a time, ships probed every inlet and bay along the east coasts of both continents, confident that anything so large had to be bisected somewhere. But the search was in vain and gradually the searchers were forced to increasingly move their attentions south and north. Although a passage at the southern tip of South America was found by Magellan and often used, it was hardly convenient to seagoing nations situated in the northern hemisphere. Thus the “Quest for the Northwest Passage” began in earnest.

In 1610, when Henry Hudson sailed through the Hudson Strait and down into Hudson Bay, he thought he had reached the Pacific Ocean. As things turned out, the fact that he was wrong was really the least of his problems. His crew mutinied, setting him adrift and leaving him to die; then, through an incredible feat of navigation by Hudson’s former mate Robert Bylot, they made it back to England, where they were tried for murder and acquitted. More importantly, they returned with the news that a titanic bay had been discovered in the north. Columbus wasn’t the only one confused by distances, and the theory quickly developed that there must be a strait connecting the west shore of Hudson Bay with the Pacific Ocean, most likely at the Gulf of California. They called this the Strait of Anian and it was to occupy searchers fruitlessly for many years to come.

Six years later, William Baffin (acting as pilot for the same Robert Bylot who had set Hudson adrift) took a stab at the Northwest Passage further north and discovered Baffin Bay. Furthermore, by following the coast of the bay, Baffin discovered three possible straits, any one of which had the potential to serve as the fabled Passage to the Orient. After a time, however, interest in the search for the Passage waned. Decades passed, then a century, then two, and even Baffin’s discovery gradually faded from memory until people began to wonder whether Baffin Bay really existed at all.

WHAT DID JOHN ROSS SEE?

Finally, two hundred years later, in another age, England took up the cudgel once again. Following the end of the war with Napoleon, the English Navy found itself burdened by too many soldiers and ships and nothing to do with them. In essence, the resumption of the quest for the Northwest Passage was a gargantuan makework project.

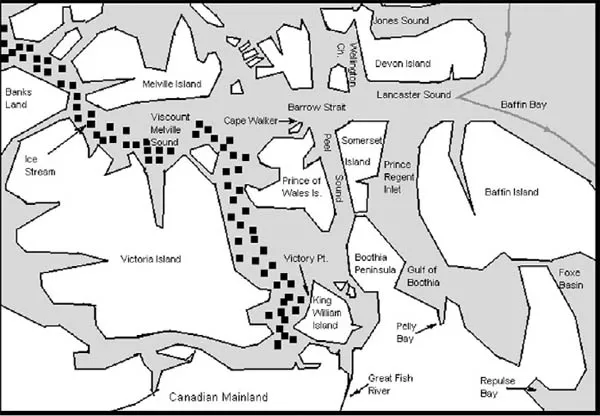

The first to take up the challenge was John Ross, a fairly standoffish member of His Majesty’s Royal Navy who believed it was not befitting for officers to mingle with the crew even when trapped for years in the frozen wastes of the high Arctic. In 1818, he sailed from England with two ships, the Isabella and the Alexander. Ross had two goals in mind: the foremost being the traversing of the fabled Northwest Passage, the secondary being to either prove or disprove the existence of Baffin Bay [see map 1].

Map 1

John Ross’ First Expedition, 1818

Since Baffin Bay did exist, Ross quickly found it. He sailed to the northern shores of the bay, then down the western coast where he rediscovered one of the straits which Baffin had reported two centuries earlier and which Ross now named Lancaster Sound. This strait was clearly headed in the right direction, so Ross decided to follow it in hopes it would lead him to the Pacific. With the slower Alexander trailing far behind, Ross had only followed Lancaster Sound a mere thirty miles when a thick fog closed in forcing him to stop. What happened next remains a tantalizing mystery to the present day.

After a short time, the officer on duty called Ross from his cabin with news that the fog was beginning to lift. On deck, Ross scrutinized the drifting veils to the west, seeking to determine what might lie ahead. Then, for just a matter of minutes, the fog parted and allowed him a glimpse of . . . something. Something that caused him to abruptly break off his journey, turn around and rush back out of Lancaster Sound “as if some mischief was behind him”.1 The amazed Edward Parry, commander of the Alexander, could only turn around reluctantly and follow his fast departing leader back to England.

Ross’ explanation for his sudden loss of heart was that he had spotted a mountain range blocking Lancaster Sound, a range that he named the Croker Mountains after the First Secretary of the Admiralty. No one else apparently saw this mysterious mountain range, and many doubted it even existed — Parry among them. And, as events would later prove, it did not exist. Ross later described the scene this way: “At three I went on deck; it completely cleared for ten minutes, when I distinctly saw the land round the bottom of the bay, forming a chain of mountains connected with those which extended along the north and south side.”2 To further explain his inexplicable flight, Ross claimed to have also spotted ice blocking their path — ice that was also not seen by anyone else.

But even if Ross believed he had sighted a mountain range blocking Lancaster Sound (or ice), that does not explain why he returned to England. The expedition had planned to winter in the Arctic. They were not pressed for time. There were certainly other bays to explore; after all, no European had visited this place since Baffin’s time. Every inlet discovered, every cove charted, would be theirs to name, their contribution to the maps of the future.

As the excellent Canadian historian Pierre Berton wondered in The Arctic Grail, “But why the haste? Why this sudden scramble to get home?” Ross’ actions placed him in the Admiralty’s black books for life, and alienated him from the explorers who would follow in his footsteps. Eventually he would return to the Arctic, but not under the aegis of the Royal Navy.

What did Ross see for those few minutes as the fog thinned to the west? What did he think he saw? A mountain range? What could have caused him to return home, destroying his career and separating him from his peers? Thus, twenty-six years before Franklin’s fateful voyage, we encounter the first question in the mystery.

What did Ross see?

EDWARD PARRY’S MIRACLE VOYAGE

After Ross, Edward Parry, having been forced to retreat once, set out to prove he was made of sterner stuff than his former leader. Parry, devoutly religious, was far less standoffish than Ross, making life for his crews in the Arctic much more bearable than under Ross. He was to command no less than three separate expeditions into the Arctic, the first being the most successful, the last the most disastrous.

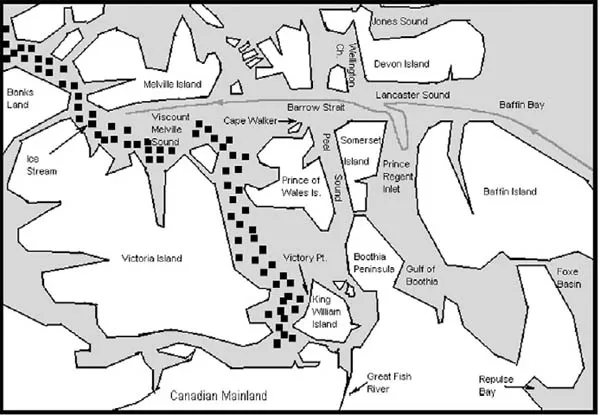

In a single season, the next year, Parry very nearly succeeded in crossing the entire Arctic from east to west by taking a straight line course down Lancaster Sound, through Barrow Strait and into Viscount Melville Sound [see map 2]. His luck was incredible. The weather turned warmer than it would ever be again for any other expedition in this period. The ice fields parted before him, the route to the Orient stretched like the Thames. Only briefly in Lancaster Sound was he halted by ice. Immediately he turned south down Prince Regent Inlet where he coasted Somerset Island before again running into ice and returning to Lancaster Sound. Finally finding a path through the ice to the west, Parry continued on to Viscount Melville Sound, eventually crossing 110 degrees Longitude, thus allowing him to claim the five thousand pound reward that the government had set.

Map 2

Edward Parry’s First Expedition, 1819–1820

But then, on the very brink of completing the Passage (and the twenty thousand pound prize that came with that feat), Parry ran up against a vast river of ice stretching across his path. Unable to find a way through the ice, he wintered near Melville Island and tried again in the spring. But all his efforts were in vain. The ice was impenetrable.

What Parry did not realize was that this river of ice originated in the permanent ice fields of the Beaufort Sea far to the northwest, where titanic mountains of ice fifty feet thick were formed. Only later would it be understood that this ice river flows south and east, through Viscount Melville Sound, then abruptly abuts up against Prince of Wales Island and is forced south down McClintock Strait and past King William Island.

But for Parry there was no alternative. Defeated on the very brink of success, he turned back and sailed home.

THE LOSS OF THE FURY

The next year, Parry set out again on his second voyage, this time to attempt a completely different route. Eschewing Baffin Bay altogether, instead he followed Henry Hudson’s old route, passing through Hudson Strait farther south, then turning north into Foxe Basin. The attempt was unsuccessful and again he was thwarted by ice.

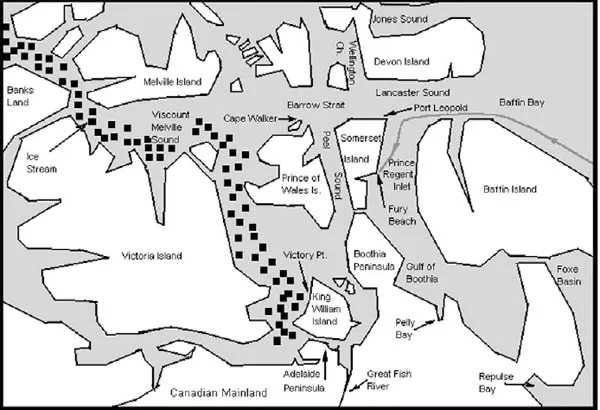

Parry’s third attempt took him over familiar ground as he passed through Lancaster Sound, then turned south down Prince Regent Inlet as he had briefly done when temporarily blocked by ice in 1819 [see map 3]. This time, however, the results were far more disastrous. Icebergs crushed one of his ships, the Fury, against the coast of Somerset Island, forcing him to abandon it and its provisions on Fury Beach. With his entire expedition desperately crowded aboard his other ship, the Hecla, they barely made it out alive.

Map 3

Edward Parry’s Third Expedition, 1824–1825

The Fury was the first ship lost in the modern search for the Passage. The loss of a ship was the ultimate failing in the eyes of the Admiralty. But, though a court martial was convened against Henry Hoppner, the Fury’s commander, he was nonetheless acquitted. Parry and his officers were praised for their efforts. Where John Ross had been ostracized for turning back, Parry was praised for losing a ship.

JOHN ROSS TRIES AGAIN

After Parry’s failed third attempt, the government cancelled the twenty-thousand-pound reward for the first ship to traverse the Passage and actively dissuaded others from embarking on the quest. But now John Ross wanted another crack at it. As official channels would not support him (indeed, they cancelled the reward precisely to discourage him), he was forced to seek private backing for his expedition and he found a patron in Felix Booth, a distillery king and sheriff of London. Aboard an eighty-five ton steam packet, the Victory, Ross followed the exact same route that Parry had taken on his third voyage.

The Victory sailed through Lancaster Sound, then south into Prince Regent Inlet where the expedition wintered on the east shore of Somerset Island and the Boothia Peninsula [see map 4]. For four years, the longest any expedition had yet remained in these waters, Ross was forced to winter on this coast, having chosen a harbour t...