eBook - ePub

The Queen at the Council Fire

The Treaty of Niagara, Reconciliation, and the Dignified Crown in Canada

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

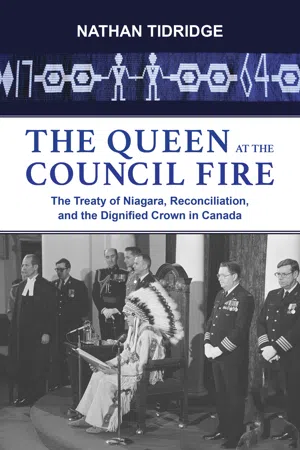

The Queen at the Council Fire

The Treaty of Niagara, Reconciliation, and the Dignified Crown in Canada

About this book

In the summer of 1764, Sir William Johnson (Superintendent of Indian Affairs) and over two thousand chiefs representing twenty-four First Nations met on the shores of the Niagara River to negotiate the Treaty of Niagara — an agreement between the British Crown and the Indigenous peoples. This treaty, symbolized by the Covenant Chain Wampum, is seen by many Indigenous peoples as the birth of modern Canada, despite the fact that it has been mostly ignored by successive Canadian governments since.

The Queen at the Council Fire is the first book to examine the Covenant Chain relationship since its inception. In particular, the book explores the role of what Walter Bagehot calls "the Dignified Crown," which, though constrained by the traditions of responsible government, remains one of the few institutions able to polish the Covenant Chain and help Canada along the path to reconciliation. The book concludes with concrete suggestions for representatives of the Dignified Crown to strengthen their relationships with Indigenous peoples.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Queen at the Council Fire by Nathan Tidridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

Encountering Indigenous Voices

My first encounter with Indigenous history stemmed from my boyhood explorations of the lake at my family cottage in Muskoka. Buck Lake, pooling out from either side of the Muskoka-Parry Sound border, was the source of many adventures as I plied its waters in an old canoe.[1] I had burned all the official maps of Buck Lake and its surrounding area, opting instead to make my own. As the years went by, I added islands, rivers, and new lakes to an expanding world of my creation. I discovered a “New World” in nearby Fox Lake, christened islands with names like Royal Britannia and Raymond Island (after my grandfather), and even touched off a canoe war with my neighbours. Over time, traditions were developed that included flags, medals, and epic histories.

Later, I attended Wilfrid Laurier University, publishing the history of my little world, which I had called “Mainland,” in an effort to preserve it indefinitely. I meticulously gathered everything together with the help of Professor Susan Scott of the Department of Religion and Culture. Susan and I would meet over tea at her home in Waterloo as she gently guided me through the passages and portages of recording personal history.

One day, as we approached what I thought was the end of the process, Susan asked me a question that changed my entire view of this world I had claimed as my own. “Nathan,” she asked, smiling at me with her hand covering her cup of tea as wisps of steam escaped through her fingers, “how are you going to handle the ideas of imperialism woven into your story?”

I could feel my canoe grinding against an unseen rock in the water.

Susan was merely enquiring about something that should have stood out as obvious to me: I had not just created my own world; I had conjured up an empire. I had projected my own identity onto the landscape of Buck Lake, and by doing so had displaced histories that had been laid down before I arrived. The very idea that other people existed on the lake and had their own worlds — just as personal and intimate — had never occurred to me.

Eventually, a new book emerged, entitled Beyond Mainland, in which I confessed, “I heard other names attached to the islands, rivers, and lakes that seemed so familiar to me. I was scared of those names — their existence implied a loss of control, that I was not the only steward of Buck Lake.”[2] I eventually learned to relax my grip and expand my view of the land and its history, accepting that many people had travelled these same waters. It was then that I first encountered the stories of Indigenous peoples of the lake and its lands. I learned that “my” lake was part of a long chain of lakes that stretched from Georgian Bay into the eastern hinterlands of present-day Muskoka, and that this chain had once served as an important transportation route and source of food for the Indigenous peoples of the region. The place I knew as the sleepy hamlet of Ilfracombe, at the foot of Buck Lake, had been visited for centuries by the Anishinaabe.

As a boy, I had never imagined Indigenous peoples living on the lands and in the waters surrounding my cottage. I had always pictured “Indians” as being from some ancient past, far removed from my life. In school, Indigenous peoples occupied the first few pages of our history textbooks before vanishing into the mists of a long timeline. Later, when I became a teacher of Canadian history, I was very tentative about exploring the place of Indigenous peoples in that history with my students. Resources were scarce and the curriculum did not ask us to dwell too much on the subject (fortunately, that has changed in Ontario).[3] The history of the Indigenous peoples of Canada mystified me; it was filled with names that were difficult to pronounce and an oral tradition that didn’t fit well with my profession’s book-centred, Euro-centric focus, or its linear approach to time. If I had to admit it to myself, I was largely ignorant of the subject. What little I knew was informed by my experience of growing up during the crises in Oka and Ipperwash (not to mention the Caledonia Land Claim that erupted during my second year of teaching). I remember the media reporting on those events with little context, fueling family discussions back home that were laced with misinformation and learned racism. Growing up in Canada, my only points of contact with Indigenous peoples were the moments of conflict that occasionally occurred, which were marked by newspapers decorated with images of Natives in bandanas or behind barricades. It never occurred to me to ask why these events were happening, or question how they were being discussed in Canada. When I became an adult, it was easier to ignore the Indigenous peoples than try and make sense of what had happened between our two peoples.

My views have changed considerably since those early days as a teacher. As my previous two books (Canada’s Constitutional Monarchy and Prince Edward, Duke of Kent: Father of the Canadian Crown) attest, for the past number of years I have been exploring the Crown in this country. It was through this exploration that I encountered King George III’s Royal Proclamation of 1763, reading that it was the “Magna Carta” for Indigenous peoples living with Canada — an assertion repeated throughout the few resources available to me. I began to realize that the Crown was at the heart of Canada’s relationship with First Nations. When the settlers and First Nations first came together to construct a delicate balance (represented so well by artist Alex MacKay’s Treaty Canoe) that would allow them to live together on the land, the Dignified Crown became the medium through which First Nations could communicate with non-Indigenous settlers.

Through my involvement with Friends of the Canadian Crown, now the Institute for the Study of the Crown in Canada at Massey College,[4] I attended the Diamond Jubilee Conference on the Crown, held in Regina, Saskatchewan, as a discussant in October, 2012.[5] This conference began to broaden my understanding of the complex relationship that has grown between the Crown and First Nations. Talks delivered by J.R. (Jim) Miller (Canada Research Chair in Native-Newcomer Relations and professor of history at the University of Saskatchewan) and Stephanie Danyluk (a research analyst in the Department of Self-Government at Whitecap Dakota First Nation) introduced me to the ancient practice of First Nations making European monarchs, and thus their subjects, kin. As J.R. Miller explained to the attendees:

Kinship and alliance are the heart of the ties to the Crown. Understanding these ties allows us to appreciate where we as a country have gone wrong in the past and, perhaps, to discern how we might improve relations in the future.[6]

In his 2014 discussion on the place of Indigenous concepts of love in Canada’s Constitution for the CBC Radio One program Ideas, Professor John Borrows (Professor of Law at both the University of Minnesota Law School and the University of Victoria) spoke of how love was woven into the treaties.

“When Indigenous peoples signed treaties with the Crown in Canada,” Borrows explained, “love was frequently invoked, even in the face of sharp disagreements.”[7]

During the September 2013 opening in Vancouver of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (the commission established in 2008 in the aftermath of Canada’s Indian Residential School System), the chair, Justice Murray Sinclair, remarked, “For the survivors [of Indian Residential Schools] in this room the most important gesture of reconciliation that they will ever see in their lives is for you to tell them that you love them.”[8]

It is here that language must be explored. Language is the atmosphere in which we live and see the world around us — that I think and write this in English immediately puts me at a disadvantage when speaking of another people. English Canadians are familiar with the issues raised by different groups speaking different languages as a result of their sometimes strained relationship with their French-speaking sisters and brothers. However, even though French and English are different forms of expression, they are rooted in a similar European tradition. There are shared experiences embracing religion, philosophy, and culture that allow their different worlds to make some sort of sense to each other.

With a common Judeo-Christian background, the Europeans who landed on this continent over the past five hundred years have shared a relationship with the environment that has deep biblical roots. Much can be gleaned about how European Canadians understand their connection to the land by reading Genesis 1:26 (New International Version): “Then God said, ‘Let us make mankind in our image, in our likeness, so that they may rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky, over the livestock and all the wild animals, and over all the creatures that move along the ground.’” Later, in verse 28, God is quoted as saying, “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.”

The use of words such as rule, sometimes translated as dominion, and subdue (originally written in Hebrew, and later Latin, before being translated into the common languages of Europe) create power dynamics between humans (made in the image of God) and the environment. Even though modern Canadian society is secular, with a clear separation between religion and the state, we cannot ignore the fact that the languages of those who migrated from Europe to these shores are the products of a Judeo-Christian world.

First Nation languages share no genes with those languages that are the products of the European concept of the world. As an example, 70 percent of Anishinaabemowin (the Anishinaabe language) is comprised of verbs — a much greater percentage than is found in any European language (English has approximately 12.5 percent in the spoken language).[9] The extensive use of analogy and metaphor, as opposed to the more common use of direct references and explanations employed by European languages, can be found throughout Indigenous communities (both historic and present-day). Anishinaabe names for places and landmarks typically reflect their relationship with them, or the location’s place in relation to the surrounding environment (For example: Toronto’s Humber River was originally called Cobechenonk, meaning “leave the canoes and go back.”) This style of naming contrasts with the European habit of designating features of the environment after significant people, places, or events.

I can offer another, specifically English, example of the problem created by language, by continuing John Borrows’s exploration of the word love. In English, we only have this one word to explain a very complex and powerful experience. In my own life I throw the word love around repeatedly: I love my wife; I love my family; I love my students; I love my morning coffee. All of these relationships are different, and yet I only have one word that conveys an emotional connection that I am trying to get across. Other English-speakers understand that I am not applying the same definition of “love” to my wife as I do my morning coffee, even though I am not giving them any other verbs to work with.

Bruce Morito addresses this idea in the introduction to his book An Ethic of Mutual Respect: The Covenant Chain and Aboriginal-Crown Relations when he cites Clifford Geertz’s notion of the “rich descriptor.” Morito explains “… where rich descriptors are used for purposes of communication, we can conclude that the people who use them appropriately presuppose a rich array of supporting and contributing intangible factors.”[10] Love is a rich descriptor, but other English-speakers appreciate that and graft their experiences and relationships onto mine, thereby understanding that my love for coffee is not familial.

Move into other cultures, however, and different words have been developed to provide names for the many “love” relationships we can have — I immediately think of the Greek concept of “agape,” or the word “mettā” from ancient India. These words are vaguely translatable into English, but their essences are not. If those languages were to die, the distinctions and experiences those words evoke would die with them.

The gap in meaning between languages described above exists between European languages and First Nations languages. As a result, one would imagine that attempts at settler/First Nations communication would be bound to fail as the worlds created by these very different realities are largely untranslatable. Paradoxically, Professor Morito offers a counter-argument: the lack of rich descriptors and the nuances in Indigenous languages that are found in English and other European languages may actually have led to a deeper relationship between the settlers and the Indigenous peoples because it necessitated careful listening and exploration of each other’s experiences. Morito explains, “the First Nation/Crown treaty relationship turned out to be deeper … precisely because both parties had to dig deeply into their imaginations and capacities to develop a shared lifeworld that people of the same culture would have [had], because they [took] so much for granted.”[11]

The referencing of Queen Victoria as “The Great White Mother,” or of King George III as “Father,” is famous in Indigenous history, and at the beginning was understood to invoke a strong relationship of equality. However, the meaning behind these rich descriptors has been lost, or deliberately corrupted, over time. When we look specifically at Anishinaabe culture and family structure, the problem with trying to explain relationships between radically different cultures becomes apparent.

Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Anishinaabe culture was very anti-hierarchical, with no concept of a paramount chief — any demonstrations of selfishness or ego was abhorred. Professor Evans Dowd, explaining the Odawa Nation in his book War under Heaven, writes, “To call leadership decentralized in these societies is almost to miss the point, because centralization was not an issue … Indian leadership was not authoritarian.”[12] Dowd explains that the Odawa term for a civil leader was ogema, i.e., a highly respected man who headed a network of extended families but held no authority to impose his opinions on others. Dowd writes, “The ideal [Odawa] leader forged alliances through displays of generosity. He was composed, dependable, and willing to withstand long hours of negotiation. He mediated disputes among his followers and between his followers and others. He received gifts and redistributed them to his people; likewise, he gathered gifts from his people and gave these, in exchanges, to others.”[13] The very idea of a leader in the community was markedly different from that of the Europeans whom they were encountering. This is especially true of women in Indigenous societies, who are often the glue that holds everything together — the “backbone of the Nation,” I am often told.

It was with words used to describe family relationships that Europeans and First Nations began to sort out their interactions with one another. The problem that immediately emerged was that the meanings of the words — different depending on the language and culture employing them — bore little resemblance to the relationship they were intended to explain. The Anishinaabe concept of fatherhood, an equal relationship within the family that involved protection and generosity, bore no resemblance to its European counterpart, which was based in a male-dominated, hierarchical society.

In her exploration of the relationship between the Dignified Crown and western Canada during the nineteenth century, the University of Calgary’s Sarah Carter explains:

… while the addresses that successive governors general delivered to First Nations, replete with references to the Great Mother (Queen Victoria) and her “red children,” spoke of inequality rather than equality from the perspective of the vice-regal visitor, this was not how they were received by First Nations, who heard powerful affirmations of their familial relationship.[14]

As Carter reminds her readers, referencing the Crown as “Mother” or “Father” was not an act of submission; instead, it was a declaration by an Indigenous Nation that they were equal members of the same family as their “brothers,” the British subjects t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Endorsements for The Queen at the Council Fire

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author

- Other Titles by Nathan Tidridge

- Copyright