- 288 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Narrating some lesser known episodes from the deep history of digital machines, Alexander R. Galloway explains the technology that drives the world today, and the fascinating people who brought these machines to life. With an eye to both the computable and the uncomputable, Galloway shows how computation emerges or fails to emerge, how the digital thrives but also atrophies, how networks interconnect while also fray and fall apart. By re-building obsolete technology using today's software, the past comes to light in new ways, from intricate algebraic patterns woven on a hand loom, to striking artificial-life simulations, to war games and back boxes. A description of the past, this book is also an assessment of all that remains uncomputable as we continue to live in the aftermath of the long digital age.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Uncomputable by Alexander Galloway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Computer Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I.

Photography

1

Petrified Photography

In Paris in the early 1860s, a sign with large lettering appeared on the facade of a modern four-story building newly constructed in iron and glass on what was then called the Boulevard de l’Etoile, stemming northward away from the Arc de Triomphe. “Portraits—from Mechanical Sculpture,” the sign touted. “Busts, Medallions, Statues.”

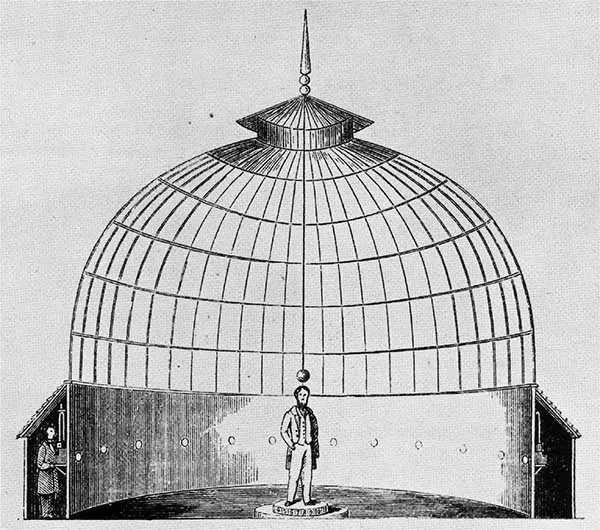

“When a large circular cupola was first erected at 42, Blvd. de l’Etoile,” one historian recounted, “constructed of metal mullions with blue and white panes of glass, it was thought to be a conservatory, a zoo for small animals in the English style, an aquarium and, only finally, a photographic studio.”1 When he visited the building’s central dome in 1863, a large chamber forty feet wide and thirty feet high (figure 1), the poet Théophile Gautier likened it to “an Oriental cupola, a weightless dome of white and blue glass.”2

Figure 1. François Willème’s reverse panopticon, a photographic studio with twenty-four cameras at the perimeter directed inward toward a central subject. Source: The Art-Journal (1864), 141.

The author Paul de Saint-Victor, who also surveyed the premises, was impressed by the hollowness of the domed photographic studio. “Imagine a vast glass rotunda containing no instruments of any kind, no apparatus visible to the naked eye, nothing to offer any indication of the wonderful operation about to transpire.”3 Gautier advanced to the middle of the rotunda, up two steps onto a pedestal and positioned his head under a silver pendant hanging to mark the exact median of the dome. “Leaving his hat on the coatrack, he tucked his hand into the lapel of his large jacket and gazed off into the distance.”4 An operator blew a whistle and twenty-four cameras opened at once. The twenty-four apparatuses were safely hidden behind false walls occupying the perimeter of the chamber. “Each camera had a primitive shutter arrangement in front of the lens; these shutters, in turn, were all interconnected, so that a single cord could be pulled to obtain two dozen simultaneous exposures.”5 A second whistle sounded, and the exposure was complete. The entire procedure lasted less than ten seconds.

The cupola on the Boulevard de l’Etoile was not a zoo for small animals, but a studio combining the arts of photography and sculpture. Bearing the name Photosculpture de France, the studio was a new commercial endeavor initiated by the artist Franç ois Willème. Willème filed a French patent on August 14, 1860, titled “Photosculpture Process,” which described a technique for producing portrait sculptures relatively quickly and cheaply.6

It was wonderful to think of the sun as a photographer, thought Gautier, “but the sun as a sculptor! The imagination reels in the face of such marvels.”7 Or as the journalist and editor Henri de Parville put it: “a sculptor and the sun will become two collaborators working together to fashion in forty-eight hours busts or statues of a hitherto unknown fidelity, of such great boldness in outline, of such admirable likeness.”8 Indeed Willème played up the magical quality of his invention, hiding the apparatus from the sitter, who likely had no idea how such a precise sculptural likeness could appear simply by bathing oneself in sunlight for ten seconds.

Seemingly magical, the sculpture in fact required several steps performed by skilled technicians. After the photographic session, craftsmen projected each of the twenty-four photographs in succession using a magic lantern.9 A pantograph was used to trace the outline of each projected silhouette, cutting the silhouette into a clay blank. “In all probability the manual input required was very substantial.”10 Artisans turned the clay fifteen degrees on its vertical axis for each number of the twenty-four tracings, producing a rough cut of the sculpture. “It is now necessary to smooth by hand, or by a tool, all the slight roughness produced by the various cuttings, and to soften down and blend the small intervals between the outlines or profiles. This is a most delicate part of the process; for it must be understood that it requires an artist of taste and judgment to perform it satisfactorily, and to impart to the work all the finish possible.”11 The technique was pure magic to Gautier. “Each number carries its own essential line, its own characteristic detail. The mass of clay is scooped out, thinned down, and given shape. The traits of the face appear, the folds of the clothing are drawn out: reflection transformed into form.”12 The hand of the sculptor had been replaced by a mechanized technique, aided by the intermediary of photography, and ultimately by the light of the sun. Solem quis dicere falsum audeat.

Willème’s sculpture instantanée was an attempt to advance a popular industrial art of sculptural portraiture for the new modern bourgeoisie, not unlike what the carte de visite had done in photography.13 “He entertained the fantasy that photosculptures, which varied in height from 35 to 55 centimeters, could be decoration pieces in the salons of the bourgeoisie, similar to daguerreotypes.”14 Willème even called his sculptural portraits Bustes-Cartes. As a commentator at the time put it: “They had, indeed, all the appearance of photographic productions, so correct were the forms and proportions, and so natural was the expression of countenance; they were, in fact, the very ‘carte de visite’ raised in solid form.”15 A fad during the years 1863 to 1868, photosculpture also produced offshoots in England and America. The technique was a hit at the 1863 photography exposition at the Palais de l’Industrie des Champs-Elysées and again at the Universal Exposition in Vienna in 1864, where Willème showed twenty-three sculptures. Willème’s final success was at the Universal Exposition in Paris in 1867, after which he retired from photosculpture. His company disappeared after 1868.

“Two observations on Willème’s process should be made at this point,” wrote Philippe Sorel. “On the one hand, it picked up on the idea expressed by Benvenuto Cellini in the mid-sixteenth century, and endorsed by Rodin in the late nineteenth century, that a statue results from the observation of a sum of profiles; on the other hand, it combined the two sculptural processes identified by Plato—removing material (cutting) and adding it (modelling).”16

Photosculpture thus has a strange relationship with chronophotography, the technique of capturing photographs through time made famous by Étienne-Jules Marey and Eadweard Muybridge. Both techniques are digital techniques—that much is clear—if we take digital to mean any mode of representation based on discrete units. Chronophotography is digital through a series of discrete photographic impressions segmented across time. Photosculpture is digital through discrete photographic impressions segmented in a spindle of space. Instead of an analysis of pictures, photosculpture relied on an analysis of profiles.

Just as one might speak of the fusion of afterimages—or “flicker fusion”—in the context of cinema, here one might speak of the fusion of sculptural sections, that is, figural silhouettes functioning as discrete dimensional samples that can be recreated into a continuous form. “Because of the law of continuity, it is not necessary to have an indefinite number of silhouettes in order to recreate the bust. A limited number will suffice, forty-eight for example.”17

Before working in clay, Willème began his research with a prototype of a woman’s head fashioned from thin slats of wood (figure 2). “This wooden head was probably shown to the Société Française de Photographie by Willème in May 1861, during the session at which he explained his new photographic process. However, the head was produced using a different technique from the one he subsequently developed and marketed. According to Willème, after taking fifty different angle shots of a statue, one hundred strips of wood were assembled two by two so that they could be cut out according to the profiles of the photographs.”18 As in the science of psychophysics and its concept of a “just noticeable difference” in the human sensorium, Willème experimented with the width of the digital segmentation in order to achieve an optimal size. His wooden head of 1861 would have thus had a “resolution” of 3.6 degrees around the vertical axis. Later, once the technique was established using twenty-four cameras, the resolution had been degraded by a factor of four to 15 degrees.

Figure 2. François Willème, unfinished photosculpture: portrait head of a woman, c. 1861. Source: George Eastman Museum.

According to Kaja Silverman, photography is “the world’s primary way of revealing itself to us.”19 Yet Willème’s technique reveals something profound, that there is an alternate history of photography in which point of view has no meaning, at least not a single point of view. The point of view, whether one or many, as in the case of montage, has so dominated how one thinks of photography, cinema, and visual culture in general that it is initially quite difficult to understand the ramifications of Willème’s technique. Two things are particularly key. First, one must proliferate the number of points of view dispersed within a space—proliferated not simply to two or four but to a mathematically significant number like twenty, or a hundred, or a thousand. Second, one must conceive of the multiple points of view as temporally synchronous; in other words, one must reject the basic premise of chronophotography, which multiplexes the image through time. Opening and closing all the camera apertures at the same moment is crucial. The resulting point of view is not “mobile,” as it might be with a handheld film camera. Instead, the view is metastable, spanning all twenty-four cameras at once. Willème’s mode of vision existed as the cumulative summation of twenty-four points of view fixed at the same instant in time.

In chronophotography or cinema, the multiplication of views leads to choice or synthesis. It leads, in other words, to montage or collage. An artist either montages a scene together by choosing which view to sequence at which time, or composites two or more image layers together to synthesize a new image. By contrast, Willème’s mode of vision was neither choice-bound nor synthetic. It was metastable. Willème multiplied the view into a “virtual” view, a virtual camera existing synchronically across twenty-four discrete apparatuses. Willème did not choose or sequence these twenty-four streams; he did not composite them backward into a single image. He maintained the metastable view as such—the view as manipulable model.

The architecture of Willème’s photographic studio (figure 1) resembled Jeremy Bentham’s design of the panopticon prison, a circular structure of peripheral cells around a central focal point. Except in Willème’s studio, the vectors of vision are all reversed. Instead of an eye at center, the watchful eye of the guard tower surveying the cells at the perimeter, Willème’s studio revolved around the prisoner’s point of view, as it were, the gazing lenses of twenty-four cameras at the perimeter all looking inward toward a single object of vision. In reversing the panopticon, Willème also reversed the normal configuration of the camera obscura, where light from nature passes through a single lens to make a single image. Willème multiplied the lenses from one to twenty-four, he arranged them inward rather than outward, and he synchronized them in time.20

For Paul de Saint-Victor, such metastases of the photographic view led not to an immaterial, omnipresent gaze but to a pure materiality, an immanent image—but a dead one. “The true mission of this useful and humble art form will be to bring sculpture into private life and to perpetuate the photographic image—by petrifying it.”21 What would it mean to petrify photography? Petrified photography is a kind of photography that has finally escaped the long shadow of the camera obscura. Petrified photography converts photography into a plastic art. And in escaping the limitations of the camera obscura’s single aperture, photography smeared itself across a limitless grid of points, neutering the axis of time while emboldening the axes of space.

2

Dimensions Without Depth

In his mon umental book La méthode graphique, Étienne-Jules Marey described a career’s worth of work inventing a variety of writing machines and honing them for scientific research. For the most part, the book addressed the inscription of wave forms onto paper rolls. From time to time, Marey concerned himself with the clipping of these curves into quantized box shapes, and hence into digital notation. The second edition of the book was expanded to include a supplement, “The Development of the Graphical Method Through the Use of Photography,” in which he reiterated the main focus of his career up to that point: “the mechanical inscription of movement using a stylus that draws on a rotating cylinder.”1

In a lecture given at the national conservatory of arts and sciences on Sunday, January 29, 1899, at nearly seventy years old, Marey spoke in detail about the development of photography, particularly the new technique known as chronophotography (taking multiple photogr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- A Letter from Paris

- Introduction

- Part I: Photography

- Part II: Weaving

- Part III: The Digital

- Part IV: Computable Creatures

- Part V: Crystalline War

- Part VI: Black Box

- Afterword: A Note on Method

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Index