eBook - ePub

Armies of the Germanic Peoples, 200 BC–AD 500

History, Organization & Equipment

- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

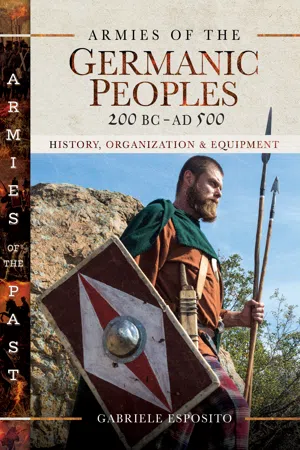

An overview of the Germanic peoples' military history from this period and an examination of the weapons and tactics they employed on the battlefield.

Gabriele Esposito begins this study by showing how, from very early on, the Germanic communities were heavily influenced by Celtic culture. He then moves on to describe the major military events, starting with the first major encounter between the Germanic tribes and the Romans: the invasion by the Cimbri and Teutones. Julius Caesar's campaigns against German groups seeking to enter Gaul are described in detail as is the pivotal Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, which effectively halted Roman expansion into Germany and for centuries fixed the Rhine as the border between the Roman and Germanic civilizations. Escalating pressure of Germanic raids and invasions was a major factor in the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

The author's analysis explains how Germanic warriors were able to crush the Roman military forces on several occasions, gradually transformed the Roman Army itself from the inside and, after the fall of the Empire, created new Romano-Germanic Kingdoms across Europe. The evolution of Germanic weapons, equipment and tactics is examined and brought to life through dozens of color photos of replica equipment in use.

Gabriele Esposito begins this study by showing how, from very early on, the Germanic communities were heavily influenced by Celtic culture. He then moves on to describe the major military events, starting with the first major encounter between the Germanic tribes and the Romans: the invasion by the Cimbri and Teutones. Julius Caesar's campaigns against German groups seeking to enter Gaul are described in detail as is the pivotal Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, which effectively halted Roman expansion into Germany and for centuries fixed the Rhine as the border between the Roman and Germanic civilizations. Escalating pressure of Germanic raids and invasions was a major factor in the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

The author's analysis explains how Germanic warriors were able to crush the Roman military forces on several occasions, gradually transformed the Roman Army itself from the inside and, after the fall of the Empire, created new Romano-Germanic Kingdoms across Europe. The evolution of Germanic weapons, equipment and tactics is examined and brought to life through dozens of color photos of replica equipment in use.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Armies of the Germanic Peoples, 200 BC–AD 500 by Gabriele Esposito in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Historia & Historia antigua. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoriaSubtopic

Historia antiguaChapter 1

The Early History of the Germani

Broadly speaking, we know extremely little about the origins and the early history of the Germanic peoples. Most of the information that we have about them comes from later written sources that were produced by the Greeks and Romans. During the opening centuries of their long history, the Germani did not create any written document that could be of help in understanding the origins of their communities. The term ‘Germani’, which will be used in this text to indicate the individuals belonging to the Germanic peoples, is a Latin one used by Roman writers. Indeed, using the word ‘Germans’ to identify the ancient inhabitants of present-day Northern Europe is considered incorrect by most contemporary scholars, since it could cause some confusion with the inhabitants of present-day Germany. What we know for sure about the Germani is that they were originally part of the various Indo-European peoples migrating into Europe from Central Asia. These, after settling over most of the continent, gave birth to a series of new civilizations that were the result of the fusion between the local cultures of Europe and the new one ‘imported’ by the Indo-Europeans. Judging by the archaeological finds related to them and the development of their heirs’ civilizations, these Indo-Europeans were extremely warlike and masters in working metals for the production of weapons as well as agricultural tools. The Indo-Europeans produced excellent swords and other weapons made of bronze, giving them a great military superiority over the indigenous populations of Europe, who could not produce such sophisticated objects made of metal. The impact of the Indo-Europeans’ arrival in Europe was different according to each geographical region, but the newcomers eventually gained dominance over all the areas that they colonized. The Indo-Europeans settling in Scandinavia, most notably in Denmark and southern Sweden, gave birth to a new culture in those areas of Northern Europe. This started to develop around 1700 BC, initiating a historical period that is commonly known as the Nordic Bronze Age, which, if compared with the Southern Bronze Age of peoples such as the Myceneans, was characterized by a series of peculiarities. First of all, it started much later than the Bronze Age of the southern peoples. In addition, it lasted much longer, since it ended only in 500 BC. In Greece, the Bronze Age came to an end around 1100 BC, more or less six centuries before that in southern Scandinavia. Consequently, there was always a big cultural gap between the civilizations of Northern Europe and those of Southern Europe. While the proto-Germans of Scandinavia entered their Iron Age only around 500 BC, the Greek cities of Southern Europe had by that time already invented philosophy and were fighting against the Persian Empire. To understand why the Greeks and Romans considered the peoples of Northern Europe to be ‘barbarians’, it is extremely important to bear in mind the existence of this great cultural difference. The differences between the various civilizations were simply the product of the Indo-European migrations’ different phases. It would thus be a grievous mistake to consider the proto-Germans as a community of under-developed and isolated northern warriors, as they actually had strong commercial links with the Mediterranean peoples and were able to produce excellent metal objects that were sold on the most important markets of the Ancient World. The territories of Northern Europe inhabited by the proto-Germans were full of strategic natural resources, especially of bronze and copper, which were of vital importance for the production of weapons or agricultural tools and thus were in high demand across the Mediterranean. Over time, the proto-Germans of southern Scandinavia created a commercial route known as the ‘Bronze and Copper Road’ that connected their territories with the Mycenean world of the south. This crossed most of Europe, from the Baltic Sea to the Black Sea, and was used to transport massive amounts of precious metals or weapons and tools obtained from metals. Thanks to their commercial activities, the proto-Germans improved their economic conditions and started to be influenced (albeit only on a limited scale) by the southern civilizations of the Mediterranean. Together with metals, the proto-Germans also exported large quantities of amber – used in the Ancient World in jewellery and medicine – which could be found only in the areas surrounding the Baltic Sea.

Map of the Roman Empire in AD 125, showing the geographical distribution of the most important Germanic tribes. (Wikimedia Commons)

Germanic chieftain with sword and round shield. (Photo and copyright by Ancient Thrace)

The Nordic Bronze Age was a fundamental phase in the history of the proto-Germans, since it was the moment during which they differentiated themselves from the other Indo-Europeans and acquired many characteristics of the future Germani. The proto-Germans of this period did not live in villages like the contemporary Celts, their settlements consisting instead of isolated farmsteads, with a single ‘longhouse’ (single-room house) plus some additional minor buildings. Most of the settlements were located on high ground and not far from the Baltic Sea. Agriculture and husbandry were practised, together with fishing in the coastal areas (the remnants of some small canoes have been found), but hunting always remained an important component of the proto-Germans’ daily life. At that time, most of Northern Europe was covered with impenetrable forests, inhabited by many wild animals. Living in such an environment was not easy, especially because so little land was available for agriculture and animal husbandry. As a result, horses were not common and only the richest members of each community could afford one. In addition to the ‘Bronze and Copper Road’, the proto-Germans created a similar and parallel ‘Amber Road’; in exchange for metals and amber, they imported precious artefacts to their northern lands, most notably vases. According to archaeological finds, the early religion of the proto-Germans had a lot in common with that of other Indo-European peoples, consisting of a sun-worshipping cult associated with the adoration of various sacred animals such as horses and birds. Similar to the contemporary Celts, the proto-Germans also sacrificed animals and weapons by throwing them into lakes. This ritual practice has preserved (albeit accidentally) many original weapons produced in southern Scandinavia, which have been discovered by archaeologists during the last two centuries.

The Nordic Bronze Age eventually started to be influenced by the southern Hallstatt culture of the Celts, and some of its main features were modified. Around 500 BC, the modifications had solidified, and thus from this date it is possible to speak of a new proto-German culture. This is commonly known as the Jastorf culture, from the name of a village located in Lower Saxony where archaeologists have found many objects related to this new phase in the history of the Germani. Broadly speaking, the territorial extent of the Jastorf culture was much larger than that of the settlements related to the Nordic Bronze Age, comprising most of northern and central Germany in addition to Denmark and southern Sweden. The Hallstatt culture, which was dominant in southern Germany, was quite different and much more advanced than the culture of the Nordic Bronze Age. Hallstatt is a small village located in the mountains of Austria, near Salzburg, which has become famous due to the rich Celtic burials that were found on its territory (in the proximity of a lake) during the nineteenth century. The name of the village, like many other important archaeological sites in Europe, contains the term ‘halle’, which usually related to the presence of salt in its territory. Salt was the equivalent of gold during the Bronze Age, and even before, playing a key role in commerce and trade. As a result, possessing a salt mine could determine the fortunes of a community. Salt was a major source of wealth and a fundamental element in the daily life of the time: it was precious enough to be traded for other goods (for example, metal weapons) and was universally used to preserve food. The Celts of southern Germany paid for the metals and amber bought from the proto-Germans mostly with salt. The early Celtic communities of Austria grew rich thanks to the salt trade and soon started to expand their political influence towards bordering territories. Within a few decades, their area of control reached the Rhine on the frontier of France and the Danube on the western border of modern Hungary. During these early centuries, however, Austria and Switzerland remained the core of the Celtic territories. The Alps were rich in mineral resources which the Celts needed in order to maintain their commercial supremacy over other peoples. Consequently, the Celts never expanded north towards the lands of the proto-Germans, but their more advanced culture was partially adopted by the communities of northern Germany and southern Scandinavia. The Jastorf culture and the Hallstatt culture had two main elements in common: the practice of cremation for burials and the production of sophisticated weapons and working tools made from metal.

Germanic warriors living on the Rhine frontier; the figure on the left is armed with a throwing javelin. (Photo and copyright by Ancient Thrace)

Germanic warrior equipped with club and hexagonal shield. (Photo and copyright by Ancient Thrace)

Around 500 BC, while Greece was at war with the Persian Empire and Rome was struggling to become a Republic after having been ruled by kings, the Celts of Central Europe started to develop a new ‘culture’ that would correspond to the second and most important phase of their history. This is commonly known as La Tène culture: as with the Hallstatt culture, its name derives from the main archaeological site where important remnants of it were found. ‘La Tène’ meant ‘shallow waters’ in the Celtic language, and the site bearing this name is located on the north side of Lake Neuchatel in Switzerland. This place surely had an important religious meaning for the Celts, because it was a site where they made rich offerings to the gods in the form of weapons and other objects that were deposited in a lake. The site was first discovered in 1857 when the water level of the lake dropped, but most of the objects were collected during the period 1906–1917. Thanks to these numerous findings, it has been possible to understand the differences between this new culture and the previous Hallstatt one. First of all, the Celts of La Tène had different burial rites from their ancestors: nobles were buried in light two-wheeled chariots rather than heavy four-wheeled wagons. In addition, the various objects from this new phase of Celtic history show a completely different artistic style. The art of the Hallstatt culture had been characterized by static and mostly geometric decorations, while the new La Tène culture featured many movement-based forms. Most of the weapons and other objects were now decorated with inscribed and inlaid interlace or spirals. The famous neck rings known as ‘torques’ and the elegant brooches known as ‘fibulae’ started to be produced on a massive scale during this period, becoming objects of universal use in the Celtic world. Stylized and curvilinear forms, representing sacred animals or plant elements, started to be reproduced on many artefacts. Celtic art was no longer based on abstract motifs, but tried to reproduce the natural world from a religious point of view. As is stressed by many scholars of the period, the La Tène culture was the result of the continuous cultural and commercial contacts that the Celts had with the Mediterranean world: Greek, Etruscan and Roman influences all contributed to the development of this new phase of Celtic civilization.

The new La Tène culture influenced the Germani like the previous Hallstatt culture, but its diffusion in central and northern Germany was very slow, taking place only around 400 BC, one century later than its early development in the Celtic world. The Jastorf culture of the proto-Germans lasted from 500 BC to AD 10, and it was during this long period, around 120 BC, that the proto-Germans first came into close contact with the southern peoples of the Mediterranean. This event was fundamental for the development of their identity and marked the transformation of the proto-Germans into Germani. The key event in this historical process was the Cimbrian War, which saw the migration of two major Germanic tribes towards the lands dominated by the Roman Republic. It should be noted, however, that some communities of Germani had already been in contact with the Mediterranean world well before that date. During the period from 500–400 BC, the Jastorf culture was mostly influenced by the Hallstatt culture, ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 The Early History of the Germani

- Chapter 2 The Cimbrian War

- Chapter 3 Julius Caesar and the Germani

- Chapter 4 The Campaigns of Augustus in Germania

- Chapter 5 Arminius and the Battle of Teutoburg

- Chapter 6 The limes of the Rhine and the Marcomannic Wars

- Chapter 7 The Migration Period and the Battle of Adrianople

- Chapter 8 The Sacks of Rome and the Battle of the Catalaunian Plains

- Chapter 9 Weapons and Tactics of the Germani

- Bibliography

- The Re-enactors who Contributed to this Book