![]()

CHAPTER ONE

ENTER THE BUCCANEER

GRAHAM PITCHFORK

In November 1940, 21 elderly Swordfish bi-planes took off from HMS Illustrious and effectively destroyed the Italian Fleet at Taranto. Just six months later, in May 1941, the torpedo-carrying Swordfish of HMS Ark Royal crippled the Bismarck and sealed the fate of the mighty German battleship. Within a few months, carrier-borne aircraft of the Imperial Japanese navy had wreaked havoc at Pearl Harbor and, three days later, sent two of the Royal Navy’s battleships, HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse, to the bottom of the South China Sea. As the war came to an end in 1945, aircraft carriers operating in the Pacific had formed the cornerstone of the Allied victory against the Japanese. The reach and devastating power provided by carrier-borne aircraft had been amply demonstrated, and the aircraft carrier had quite clearly replaced the battleship as the capital ships of the Fleet.

The end of World War Two may have seen the demise of the menace of Nazism and Japanese imperialism, but it would soon herald an uneasy peace, and the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 emphasised the dangers inherent in the new world order of the ‘Cold War’. The Soviet navy had previously been limited to coastal operations geared to the defence of the Soviet Union, but a significant increase in their warship-building programme highlighted the emergence of a global capability posing a great threat to the security of the vital sea-borne trade of the Western Powers. Pre-eminent in the Soviet shipbuilding programme was the development of the 17,000-ton, heavily gun-armed Sverdlov cruiser.

During the war years there had been major developments in radar technology, and the capability to detect high-flying aircraft at long range had been achieved. However, the shape of the earth dictated that an aircraft flying just above the surface would not enter the ‘lobe’ of enemy radar until it reached a range of some 26 miles. Flying at very high speed and very low level, an attacking aircraft would give a target as little as three minutes’ warning of an impending attack. The surprise element of such an attack had been recognised by the staff of the Naval Air Warfare Division and in 1952 they realised that this was the answer to the threat posed by the Sverdlov. The following year the Navy Board issued Specification M.148T for a two-seat, carrier-based strike aircraft capable of delivering nuclear and conventional weapons over long ranges and at high speed. Naval Air Requirement NA.39 was issued the following year.

The primary role of the aircraft, as specified in the requirement, was to be effective at attacking ships at sea, or large coastal targets, which would be radar-discreet and identifiable at long range. The primary weapons were listed as the ‘Green Cheese’ anti-ship homing bomb and a tactical nuclear bomb, with an additional requirement to deliver a large range of secondary weapons. The aircraft also would have the ability to act as an air-to-air refuelling tanker. The operational profile envisaged a 400-mile radius of action, with a descent from high level to very low level just outside the detection range of a target’s radar, followed by a high-speed low-level dash to and from the target. Stringent weight limits were imposed so the aircraft could operate from and be supported by the Royal Navy’s current aircraft carriers. This meant having maximum take-off and landing weights and ensuring the aircraft’s size enabled it to be lowered to the ship’s hangar by the lifts.

The naval requirement set a daunting technical challenge, but most of the major British aircraft companies submitted designs. At the end of March 1954, five companies were invited to tender for the order of 20 development aircraft. The Blackburn and General Aircraft Company at Brough were successful with their B.103 design and the initial go-ahead for production was given in July 1955. Although a small company compared to other British aircraft manufacturers, Blackburns had a long history of producing aircraft for the Royal Navy, but B.103 was their first venture into the jet age.

Achieving the necessary landing speeds for carrier operations posed a particularly difficult challenge and most companies utilised the benefits of ‘jet deflection’, which was at the early stages of development. Blackburns investigated the benefit of boundary-layer control, achieved by blowing high-pressure air, bled from the engines, over the leading edges of the wing and tailplane and over the flaps and ailerons in order to obtain increased lift and thus reduce landing speed. The net value of these measures was an approach speed with full flap and aileron droop some 17 knots slower than an ‘unblown’ approach. This method provided significant advantages over the jet deflection method and also allowed the Blackburn design to employ a smaller wing – an important feature for high-speed low-level flight. The need to generate high bleed-air pressure from the engines for the approach and landing phase resulted in a high engine RPM and an unacceptable landing speed. A large airbrake, forming part of the aft fuselage, was the answer. With it fully extended, the appropriate approach speed could be maintained and this became the standard landing configuration for the aircraft. A T-tail had already been selected but the position of the airbrake made this inevitable.

Another advanced feature was the embodiment of an ‘area rule’ design, which allowed a reduction in the amount of thrust required to maintain maximum cruising speed. This offered the bonus of a larger internal rear fuselage size for the storage of avionics and fuel. The structure of the aircraft was based on two large machined steel spars used in the inner wing, with integrally stiffened machined skins on the thin wings and the all-moving tail-plane giving the aircraft added strength. Generations of Buccaneer aircrew have extolled the virtue of their aircraft’s strength over the years. To some it was akin to the proverbial brick-built s*** house! The folding nose contained the radar, and the design of a 180-degree rotating bomb door for an internal bomb bay capable of carrying 4,000 lbs of stores was unusual and would provide an added bonus in later years when an external fuel tank was incorporated in the skin of the bomb door.

Selection of the engines presented some difficulties and, eventually, a scaled-down de Havilland Gyron producing just over 7,000 lbs of thrust was chosen. Two engines gave the desired sea-level cruising speed of Mach 0.85, and just sufficient thrust for take-off. It is interesting to note the comments made by an independent audit carried out by American officials who made the telling remarks, ‘the airplane seems underpowered and pitch-up could be a problem’. Time would prove them right.

Just 33 months after Blackburns had been given the go-ahead, the first aircraft (XK486) was ready for taxi trials. For such a relatively small design and production team, on what for its day was a very advanced project, this represented a remarkable achievement, and particularly when compared with the ponderous progress we see on some projects today.

The Blackburn NA.39 takes off for its first flight.

By March 1958, the aircraft was ready for engine runs and these were completed at the company airfield at Brough near Hull. The small airfield was totally unsuited to operate the NA.39 and so the company arranged to lease the former bomber airfield at Holme-on-Spalding-Moor, some 18 miles from the factory. However, the Ministry of Supply deemed that the 6,000-foot runway at Holme was still too short for the first flight, so XK486 was partially dismantled, covered in a shroud and transported by road to the Royal Aircraft Establishment’s airfield at Bedford. Blackburns’ recently appointed chief test pilot, Derek Whitehead, an experienced former Royal Navy test pilot, commenced high-speed taxi runs in April. These trials suffered an early setback when a tyre blew out and damaged the starboard inner wing skin, but the engineers soon had the aircraft ready for its first flight, which took place on 30 April with Whitehead at the controls and the head of flight testing, Bernard Watson, in the rear seat. The first flight was made without using the boundary-layer control system, and the 39-minute flight was a complete success. After a further three months of testing at Bedford the aircraft finally returned to Holme and the test programme continued. Further aircraft became available and they were towed along local roads, in the early hours of the morning, from the factory at Brough to Holme airfield where they made their first flights before being allocated to specific tasks for the flight test programme.

More pilots were converted to the NA.39 before joining the flight test team, and they included Lt Cdr Ted Anson, an experienced Royal Navy test pilot who went on to become ‘Mr Buccaneer Royal Navy’, filling every Buccaneer appointment up to captain of HMS Ark Royal before retiring as a vice admiral.

The NA.39 made its public debut at the SBAC Show at Farnborough in September 1959, when Derek Whitehead and ‘Sailor’ Parker demonstrated XK490. In the following January, deck trials took place on board HMS Victorious and Derek Whitehead, flying XK523, made the first carrier landing on 19 January 1960 in difficult weather conditions. A second aircraft, XK489, the first ‘navalised’ aircraft, joined the programme and 31 successful sorties were completed, together with important deck handling, aircraft lift and hangar stowage trials.

As more of the development batch aircraft became available the flight test programme gathered momentum. Lessons learned from earlier trials were embodied in the newer aircraft and minor structural changes were made. Hot weather trials were conducted in Malta, weapons trials commenced at West Freugh, and three aircraft were attached to A&AEE Boscombe Down for completion of the Controller Aircraft (CA) Release, obtained in April 1961. These trials by C Squadron at Boscombe included full carrier trials, some being conducted from HMS Ark Royal in the Mediterranean during January 1961. One aircraft (XK526) was then shipped to Singapore for tropical trials. In the meantime, the aircraft had finally been given a name and, on 26 August 1960, the NA.39 acquired the very appropriate designation of Buccaneer S.1, the ‘S’ indicating the aircraft’s strike (nuclear) capability.

As the manufacturer’s and Boscombe Down trials continued, the Royal Navy formed its first unit with the specific task of developing operational and engineering techniques and capabilities.

The officers of 700Z Flight with Cdr ‘Spiv’ Leahy standing in the centre.

The Royal Navy’s Buccaneer Intensive Flying Trials Unit, (IFTU) 700Z Flight, was formed at RNAS Lossiemouth (HMS Fulmar) on 7 March 1961, when Rear Admiral F.H.E. Hopkins CB DSO DSC, the Flag Officer Naval Flying Training, took the salute at the commissioning parade held in Hangar Two. Cdr Alan ‘Spiv’ Leahy DSC, a highly experienced ground-attack pilot and Korean War veteran, commanded the flight.

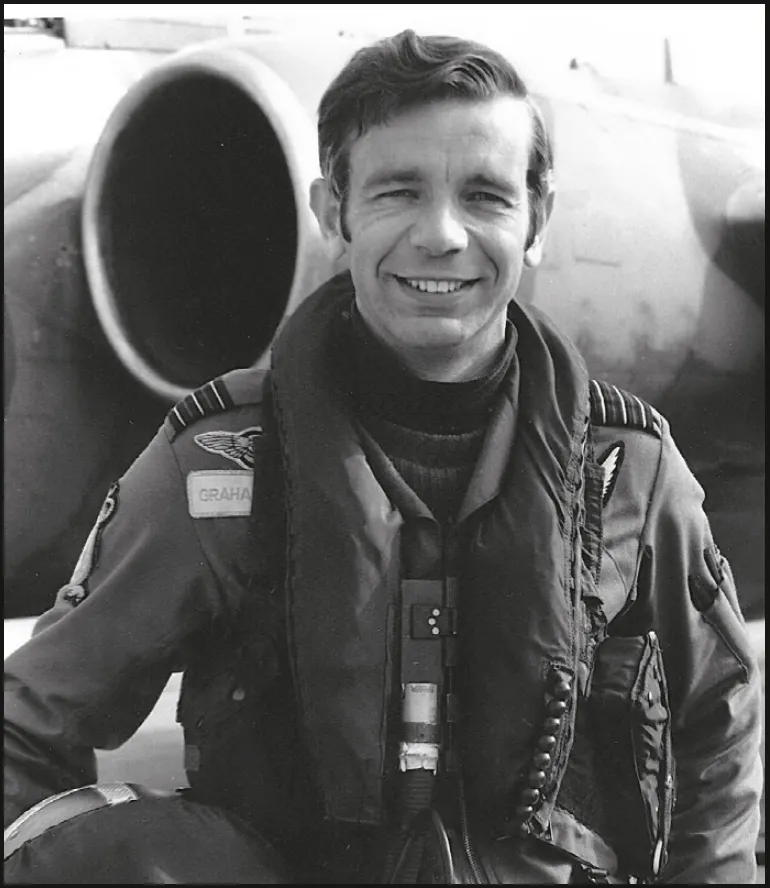

In April 1965, I joined Graham Smart at Lossiemouth on an exchange posting and we formed the first RAF crew to operate the Buccaneer. It was the beginning of three years of exciting flying that took me to the Far East, to Aden and to East Africa. After a year at sea, it was back to Lossiemouth to spend two years as an instructor with 736 Squadron – the Buccaneer training squadron – with later detachments to 803 Squadron conducting weapons trials. My abiding memory of this period of my service life was the opportunity to fly with some great aviators and make some marvellous friends.

Whilst I was with the navy at Lossiemouth, the first South African Air Force crews began their conversion onto the new, and only, export version, the Buccaneer S.50. They loved their new acquisition and flew it aggressively until 1992.

The plan for Graham and me was to gain experience on the new generation of ‘fast jet’ before heading for the TSR-2, but this was not to be. During our time at sea, two political decisions were to change my RAF career pattern. First, TSR-2 was cancelled, and then it was announced that the Royal Navy’s new carrier programme (CVA-01) was also cancelled. This latter decision was to see the end of fixed-wing flying in the navy for the foreseeable future. As a result, an increasing number of RAF officers were loaned to the Fleet Air Arm to maintain the strength of their three Buccaneer squadrons until the eventual demise of navy Buccaneers in 1978.

The first South African Air Force Buccaneer S.50 over Holme-on-Spalding-Moor.

The cancellation of TSR-2, and later its replacement the US-built General Dynamics F-111, left a huge gap in the RAF’s tactical strike/attack capability. The answer was to inherit the navy’s Buccaneer fleet, and order a new build of the aircraft to create six RAF squadrons – in the event there were only five plus the OCU. The RAF would then assume responsibility for providing tactical support of maritime operations (TASMO), and a strike capability operating from RAF Laarbruch in Germany and assigned to the NATO strike plan.

With the impending run down of the Fleet Air Arm squadrons, Lossiemouth was to close as a naval air station, with 809 NAS re-locating to Honington where the training of all Buccaneer crews, both RN and RAF, was to be carried out on the newly formed 237 OCU. The instructors were drawn from both services. It was this close professional, and social, relationship, initially on RN front-line squadrons, and then at Honington, that established the unique and lasting bond amongst the Buccaneer fraternity.

With the cancellation of the TSR-2, and then the F-111, there was a need for Buccaneer experienced crews to establish the RAF’s Buccaneer force at Honington. From a cast of one, I was dispatched to Honington to join Wg Cdr Roy Watson to establish the operations wing pending arrival of 12 Squadron in October 1969, the RAF’s first Buccaneer squadron. Little did I know that I was to spend another 12 years involved with the Buccaneer, culminating in command of...