![]()

CHAPTER I.

The Proposed Constitutional Amendments of 1903. Their Inadequacy.8

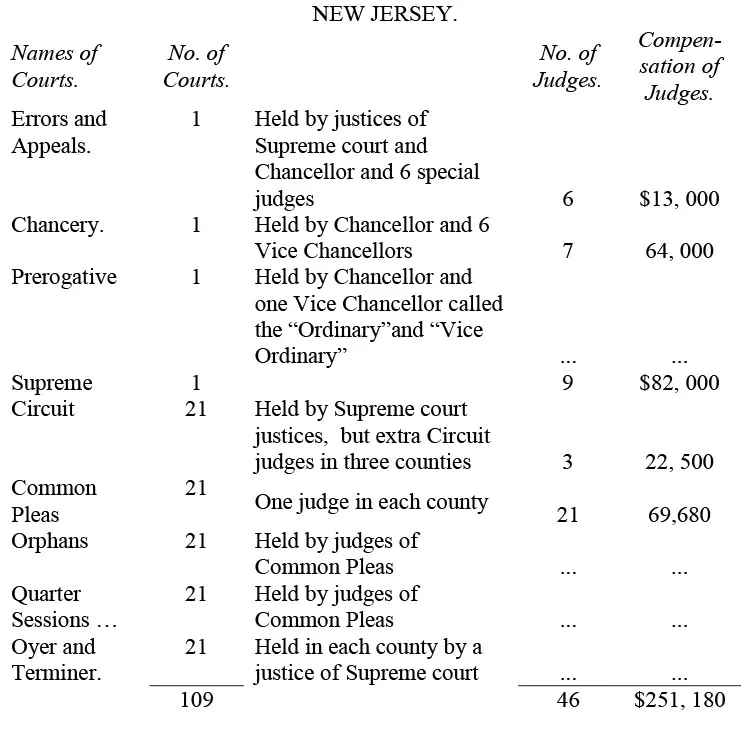

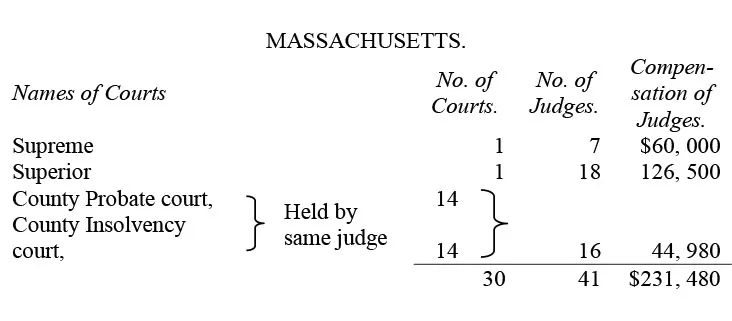

We have a curiously interesting system of courts and procedure. Its fundamental architecture is English of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. We have at sundry times torn out great sections of the old building and, piece by piece, have added wings and “lean-tos,” so that the whole structure is now very quaint and picturesque indeed. Note what the names suggest: Court of Quarter Sessions, Court of Oyer and Terminer, Court of Common Pleas, Orphans’ court, Circuit court, Supreme court, Prerogative court, Court of Chancery, Court of Errors and Appeals. Mark the contrast in Massachusetts, where the list is: Supreme court, Superior court, county Courts of Probate and Insolvency, and that is all, above the municipal courts. You must be careful how you walk in these our halls of justice, for if, by mistake, you enter one with a legal controversy which belongs to another, you will be ejected and fined in costs. Some of them, too, have different entrances for different kinds of cases, and it is deemed of essential importance that in bringing this case you enter by this door, and, with that case, that door. If you mistake in your choice, you will be mulcted in costs and perhaps turned out or compelled to retrace your steps. This, by force of the ancient traditions which have governed our craft since the days of the Edwards, kings of England. But the structure and its traditions, so interesting to antiquarians, are somewhat inconvenient for the uses of the twentieth century. Until recently these inconveniences were experienced only by suitors. They waited while the lawyers disputed before the judges, for months or years, through which door or into which court the controversy ought to have been carried. A century ago people had time for such delays. While it was only the suitors who waited, we lawyers did not deem the inconvenience unbearable, for in the settlement of these points of procedure—very interesting to us—we found much to do, and on the dicision of each point costs accrued to the lawyers on both sides, the only question being which of the opposing litigants must pay them. In the phrase of Wall street, there was an “active market.” But recently, our business has accumulated so fast that it threatens congestion in the Court of Appeals. We may have to wait for a hearing in all our cases, including those which, to the surprise of the litigant on the one side and to the consternation of his opponent, we have made to turn upon these latent and interesting points of procedure. Our clients must wait, too; but if that were all, it is probable that we could endure it. We do not complain when, upon a prompt hearing, the Court of Appeals decides that we began in the wrong court, that our client must pay costs and begin over again. Who thinks of a constitutional amendment to stop that delay? But if we must wait, as well as our clients, it will indeed become intolerable. So our State Bar Association has determined to make a reform by a constitutional amendment. True, we have not gone about it in a very statesmanlike way. We have made no inquiry respecting the great tide of judicial reform that has swept over America, England and her colonies within the last century. “What have we to do with abroad?” And, in respect to legal procedure, every place beyond New York and Pennsylvania is “abroad” to us lawyers. It seemed to be much simpler to add another lean-to to our judicial structure. We want a new court, a new Court of Appeals. It is true that neither the United States nor any other state in the Union, except New York, has a Court of Appeals above its Supreme court. It is also true that New Jersey has more kinds of courts than any other state. But our present courts do not suffice to decide our lawsuits promptly—which is small wonder, seeing that our procedure sometimes requires two or three suits to settle one controversy or, by dint of our dexterous tripping of each other’s steps, compels the courts often to hear a single controversy several times. I have collected, in a series of articles in the Law Journal, over fifty reported cases in illustration of such doings, merely as instances of classes of other like cases. Travelers sometimes ask why we do not simplify our judicial system and even tell us that in remote countries, like Connecticut, Canada, England, and Australia, these problems of simplifying ancient procedure have been solved in statesmanlike reforms in which the mistakes of hasty states, like New York, have been avoided and which are found satisfactory after a quarter century’s use. But most of us are agreed that such reforms cannot be successful. It is, a priori, impossible. Then, too, those regions are too remote to interest us. Look over the river at the procedure in New York! And finally, after all, the costs of these delays do not fall upon us. So let us ask the people to give us a new court. It will create five new judgeships, each of which ought to carry a salary of twelve to fifteen thousand dollars; for the judges of the inferior Supreme court get nine thousand, and the state will save the cost ($12,000 or $15,000) of the present Court of Appeals.

![]()

CHAPTER II.

The Judicial System of New Jersey.

Our system of courts at present is the most antiquated and intricate that exists in any considerable community of English-speaking people. Inherent in the cumbersome plan of tribunals is a system of procedure quite as antiquated and far more intricate. Both courts and procedure were brought here from England by our colonial forefathers and were worked into a shape fitted to the needs of a rural community of Eighteenth century colonists. They are fundamentally in that shape to-day. Meantime the people of the state have become a great industrial and commercial community, yet there has been no change in the plan of the judicial machinery corresponding to the enormous change in the volume and character of the work which the new conditions of the people bring upon it. Important reforms in details there have been, but, though we have patched the machinery and altered or added a shaft or a wheel here and there, it is still an Eighteenth century provincial mill built upon an English model of the Middle Ages.

The people of the state maintain their courts to settle their legal controversies, yet no suitor can be sure in any case, when his lawyer brings the controversy into court, that it will be settled in that suit. After months or years of legal combat his suit may be dismissed because it was brought in this court instead of that, though both were civil courts of general jurisdiction, held by judges abundantly competent to determine the case upon its merits. During nine successive terms of the Court of Appeals five cases were dismissed by that court on that ground, and in four of the five the Court of Appeals reversed the decree of the court below on that ground.9

Or a litigant having a just and lawful defense may find that the court in which he is sued must give judgment against him, because it has no authority to consider that particular defense. Then he must begin a new suit in a second court to prevent the first from enforcing against him a judgment which would deprive him of his lawful rights. Or the suitor may find at the outset that, in order to settle the controversy, he must bring two different and successive lawsuits in different courts. For example, if my neighbor and I dispute the question whether he has the right to drive his wagon at his pleasure across my lot, I must bring one suit in one court to prove that he has no such right, and, having obtained judgment in that, I must then bring another suit in another court to prevent him from violating the right by driving across the lot. And either suit may, at any time, be set back to the initial stage, or even come to a futile end, upon the sudden appearance of some hidden flaw in the legal procedure by which is raised a technical question of no interest to any one in the world except the lawyers and judges of this state.

No human knowledge or wisdom suffices to insure against these technical flaws. For whether or not they exist, depends sometimes upon subtle legal distinctions upon which the court below may hold one opinion and the Court of Appeals another; and on which, moreover, an infinite series of Appellate courts might well hold an infinite series of differing opinions.

I think that it must have been New Jersey to which Lord Coleridge, Chief Justice of England, pointed when he said, “I am told there is a state in this progressive Union in which they” (the subtleties of the ancient procedure) “are at this moment as alive as ever, and I venture, therefore, upon this subject to make you a practical suggestion.” (Then, after referring to the reservation by Americans of a great National Park, the speaker continued): “Could it not be arranged that, with the sanction of the state itself, some one state should be preserved as a kind of pleading park, in which the glories of the negative pregnant, pleas giving express color, absque hoc, the replication de injuria, rebutter and surrebutter, and all the other weird and fanciful creations of the pleader’s brain might be preserved for future ages to gratify the respectful curiosity of your descendants; and that our good old English judges, if ever they revisit the glimpses of the moon, might have some place where their weary souls might rest—some place where they might still find the form preferred to the substance, the statement to the thing stated.” (Lord Coleridge’s address (1883), N. Y. State Bar Assn. Reports, Vol. 7, p. 39.)

England, whence we inherited these medievalisms, and many of her self-governing colonies and many of the older states of this Union have had, at some time in their history, substantially similar judicial systems of the antiquated pattern which we still retain, and substantially the same medieval procedure. Precisely such abuses as I have pointed out caused prolonged investigations in England, and successful reforms there and in her colonies and in some American states.

Every English-speaking community (with the possible exception of a few of the smaller colonies whose judicial systems I have not examined) has now a simpler system of courts than that to which our lawyers cling with superstitious reverence; and England and most of her self-governing colonies and far the greater number of our states have simpler methods of procedure. New York alone, among those that have made these reforms, has gone to such extravagant lengths in recent years as to over-shoot the mark and to bring into her procedure a worse confusion than she had expelled by earlier and wiser reforms. This remark applies only to her procedure. Her system of courts is simple and excellent.

[In these circumstances our State Bar Association some two years ago (in 1900) appointed a committee of eminent lawyers to advise amendments to the plan of our constitutional judiciary. One might have expected that the committee would ascertain the experience of other Anglo Saxon communities which had made reforms in a system of administering justice substantially common to them and to us, and would have reported, in the light of that information, some moderate measure which would remedy the worst abuses, and give us the benefit of the tried and successful reforms of other states and countries using Anglo-Saxon law. The committee did nothing of the sort. Not a word nor a comment did it offer upon any other attempt at reform. For aught that it tells us, there might as well have been no advance in the administration of justice outside of our own state; nor, for that matter, any delay or miscarriage of justice within it. The committee did not propose to abolish a single unnecessary court, not a single mischievous form of procedure. It proposed to substitute a new Court of Appeals for an old Court of Appeals, and to add one more class of cases to those which may be appealed. That is the extent of the committee’s reforms. Other provisions are added in its proposals, but they are subsidiary and of little interest to any save lawyers and judges.

Many advantages, we are told, will follow the proposed changes if they are adopted. A clumsy Court of Appeals will be succeeded by a court of smaller number and of higher average ability. The present Appellate court sits at long intervals; the new court will sit continuously while there is business for it to do. The former, for want of time, is believed to give scant attention to some cases; the latter will have ample time for adequate consideration of all cases.

All that may be true, but there is no need for either court. The Supreme court is abundantly competent to be the court of last resort. Is not the Supreme court of the United States a court of last resort? All other states in the Union, except New York, are satisfied to have a Supreme court perform that function. That court is the one institution which every other state has preserved, with sedulous care, at the head of its judicial system.]

New Jersey and Massachusetts have about the same area, seven thousand eight hundred and fifteen and eight thousand three hundred and fifteen square miles, respectively. The former is divided into twenty-one counties, the latter into fourteen. New Jersey has a population of eighteen hundred thousand; Massachusetts of twenty-eight hundred thousand (census of 1900), and their wealth in 1890 was, for the former, one billion four hundred and forty-five million; for the latter, two billion eight hundred and three million. The following is a comparison of their judicial systems above the grade of municipal courts:10

In each of twelve counties of Massachusetts one judge holds the Probate court and the Insolvent court. In each of the other two counties there are two judges to hold those courts.

It should be stated, however, that the trial docket in Boston is much in arrear.

What have England and her colonies and other states of this Union done towards getting a simple and effective judicial system and procedure? And what have been the practical results? Have they all made a mistake in discarding the machinery which we retain, and have we been wise in refusing to change?

[The plan of the committee of the State Bar Association was adopted by the legislature last winter without discussion, but the legislative action failed for want of the publication required by the constitution. It will be again presented to the legislature this winter and will probably be adopted. It must be again submitted to the next legislature and, if approved, the people must then vote upon it. Meantime our medieval legal system remains. The taxpayer stands the needless expense, the suitor the delay and miscarriage of justice—that is, for the present. But the people have not been reckoned with. Will they, too, adopt the plan without discussion?]

The paragraphs in brackets were written in January, 1902.

![]()

CHAPTER III.

The Court Systems of the New England States. Getting Into the Wrong Court.

Let it be said, once for all, that I shall not deal with courts below the grade of County courts, nor with local courts like those peculiar to certain cities. The state systems of county and superior tribunals are to be compared.

Throughout New England the judicial systems of the states are nearly as simple as that of Massachusetts. In each there is one supreme tribunal, appropriately called the “Supreme Court,” or “Supreme Judicial Court,” which is the court of last resort.

In Connecticut this tribunal is called the “Supreme Court of Errors.” It consists of five judges and its jurisdiction is appellate only. There is also, as in Massachusetts, a Superior court, consisting of eight judges (beside these, the justices of the Supreme court are ex-officio judges of the Superior court, but they do not sit in it unless specially assigned to do so). Probate courts, held by single judges, one in each “Probate District,” complete the state judicial system. Special local courts are five Courts of Common Pleas in five of the larger counties, and a “District Court” at Waterbury, embracing a number of towns.

In Rhode Island the Supreme court, consisting of seven judges, is divided into an “Appellate Division,” held by four of them, and a Common Pleas Division,” held in each county by one or more of the judges for the work of trying cases. The only other courts in the state system are the Probate courts, which from very early times in its history have consisted of the town councils. This is still the state system of Probate courts, though the towns are allowed to substitute a Probate court held by a single judge, if they choose to do so.

In the sparsely-settled states of New Hampshire and Maine the judicial system consists in each state of a Supreme court and Probate courts only, except that in Maine Insolvency courts are held by the probate judges, and two or three counties have each a “Superior Court” of narrow jurisdiction.

In Vermont the judicial system is a Supreme court, consisting of seven ...