- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This accessible case study offers a fully rounded picture of Zambia's course since independence, chronicling the periods of boom and decline after the fall in the price of copper around the mid-1970s. The author advocates an internally oriented economic strategy to retain industries and livelihoods and investigates the ability of the current leadership to achieve this.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Introduction

DOI: 10.4324/9780429267987-1

To the visitor new to Central Africa, Zambia and its peoples present a set of confusing and intriguing impressions. After stepping off the airplane, train, car, or bus, one is immediately confronted with a country that seems to mix together European and African realities. In the rural areas, roofs are of thatch, roads are dirt paths, and the way of life is pastoral and rather slow. As one approaches the urban centers and the mining towns, the houses are brick with tin or shingled roofs, roads are tarred, and the pace of life approximates any medium-sized Western city. In the capital itself, Lusaka, visitors are often heard to exclaim, "this doesn't seem like Africa at all!"

These two realities exist side by side in modern Zambia and sometimes give the observer the false impression that there really are two separate worlds in Zambia. Yet the people in the rural and urban settings are not distinct—their histories and their families are intertwined. And the future of the country is bound up in the balance to be struck between the countryside and the city, between mining and agriculture.

Zambia has some of the richest deposits of copper and cobalt in the world. Gigantic industrial mines have until recently been premier exporters of high-grade copper to industrial economies of the West as well as Japan and China. To add to that great resource advantage, Zambia has the reputation of being one of the most stable countries in Africa. As of 1987 it boasted the same chief executive since independence in 1964, Dr. Kenneth D. Kaunda, Zambia has had regular elections, a civilian government, and no successful coup d'états to date. The first decade of independence was a period of prosperity and hope. The new government proclaimed its commitment to a brand of socialism and then invested heavily in social welfare programs, which improved the lives of many Zambians. The copper price was high and money was available for an ambitious national development plan as well as for comfortable living by the new black elite. A tumultuous period of multiparty politics (1964-1972) was followed by apparent internal stability with the promulgation of one-party rule in 1975

In the mid-1970s this calm and prosperity began to give way to growing economic difficulties, greater social inequalities, and dislocation. Although potentially one of the strongest economies in the region, by 1985 when this study concluded, Zambia was experiencing a serious economic decline from which recovery is not at all assured. From 1974 to 1980 the gross domestic product (GDP) per capita declined by 52 percent.1 Private consumption shrank by 21 percent from 1975 to 1979. The mines, which had provided much of the state's revenues until 1974, now contributed little to the nation's treasury.2 Yet in the midst of this economic crisis, the rich grew richer. According to an International Labor Organization (ILO) study the richest 5 percent of the population by 1976 controlled 35 percent of total incomes;3 by 1985 the accumulation of wealth in the hands of a few was even more extreme. What happened to the mineral-based economy that caused such a rapid decline? How in the face of the rhetoric of socialism and the reality of many social welfare programs had Zambian society fragmented into such extremes of wealth and poverty?

Signs of political discontent surfaced in the 1980s, starting with an attempted coup d'état in 1980 and marked by constant murmuring against the regime; The electoral system continues to be plagued by growing apathy among voters, indicated by a declining party membership though masked by enforced voter registration campaigns. Within government, the executive steadily accumulates power, the focal point of rule is more and exclusively the president, his advisers, and personal office. Despite these political signs of stress and the overall economic crisis, the country remains stable. Why is this so? What does the future hold in a system where there is no well-defined successor to the president or opening for legal opposition? In the 1980s several prominent Zambians became involved in the international drug trade; former members of the government were investigated and detained for their involvement. What within the Zambian elite encourages such activities? Why, in light of their considerable personal wealth, do they become involved in this illegal and dangerous form of international commerce?

At independence Zambia followed the development orthodoxy of the day and attempted to industrialize using an import-substitution strategy. This strategy is based on the notion of limiting imports by supplying those needs internally, thus constructing factories to supply intermediate and final consumer goods to the population and other industries. This seemingly logical strategy has left Zambia in the 1980s with a desperately underproductive network of state-owned companies, many of which are permanent lossmakers, with most operating way below capacity. What went wrong with this approach? Do the prescriptions of the "Aid Doctors" (the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) primarily) hold much hope for the ailing manufacturing sector of Zambia?

In 1975 Zambia was one of the few non-oil exporting nations with a substantial balance-of-payments surplus.4 By 1985 the country was deeply in debt and behind in repayment of interest on the external loans. Foreign suppliers were threatening to cut the country off and politicians were forced to invoke some rigorous and unpopular policies in order to try to keep the economy afloat on IMF loans. What happened in this decade to drive Zambia from a comfortable international trading position into international debt peonage? Why do international banks think it worthwhile to keep Zambia afloat?

Although Zambia is known to have great agricultural potential, tsetse infestation, unreliable rainfall in certain areas, and high internal production costs have slowed down the development of commercial agriculture. Beginning in 1975 President Kaunda and other political leaders began proposing a "back to the land" policy, arguing that Zambia's future is in agriculture. Given that this is supposed to have been the government policy for over a decade, why has so little development taken place in agriculture? As of 1985 a few hundred large commercial farmers (many of them expatriates) still provide most of the food for the towns, while the bulk of the peasant producers only service the familial and local markets. Between 1979 and 1981 over 30 percent of the annual marketed maize (the staple food) needs for Zambia were supplied by imports.5 What lies behind this inability or lack of desire to reorient the economy toward agriculture, especially with the pressures in that direction from external aid agencies? How likely is it that Zambia's leaders can successfully encourage people to turn to peasant farming?

Much of the discussion of Zambia's achievements and problems centers on the personality of President Kaunda. Not only has he dominated domestic politics since 1964 but he is also the symbol of Zambia's complex and contentious foreign policies. President Kaunda has become an important Third World spokesperson, but he has great difficulties in diplomacy close to home. With the nation located in the cauldron of racial and regional wars in southern Africa, Zambia's leader has attempted to maintain a fragile balance between warring parties and also act in accordance with Zambia's own economic needs. Of prime importance have been trade and transport links; a constant factor has been ambiguous relations with the regional giant South Africa. Officially, the government has always taken a strong stance against the immoral apartheid policies of the Afrikaner leaders. More quietly, Zambia has traded extensively with the Republic of South Africa. In the early 1980s, when certain of the economic restraints connected to the struggle for Zimbabwe had been removed, the Zambians seemed to be drawing closer still to their announced enemies. In late 1985 the shops in Lusaka were filled with goods made in the Republic of South Africa. What is the nature of Zambia's relations with South Africa? Do the new regional pacts, such as the Southern African Development Coordination Conference (SADCC) or the Preferential Trade Agreement (PTA) offer Zambia greater flexibility in developing economic alternatives to ties with Pretoria?

This book attempts to answer some of these questions by tracing details of policies and allocations of funds in some cases and in others by discussing battles over policies. To answer the more interesting questions, I turn to the key features of the political economy and the nature of the class that runs Zambia, whom I call the "governing class" to distinguish it from an external "ruling class."5 In such new societies, the full outline of a class configuration is as yet quite hazy, but the nature of the local dominant class already affects the making of policy and also helps explain the intractability of some of the problems Zambia faces. The social basis of the unions in Zambia is explored to understand the evolution of early politics and the reasons for the fragmentation of the nationalist alliance. Finally, the plight of the peasants and the urban poor is discussed as a sad outcome of policies since independence. I begin with a review of Zambia's precolonial and colonial history to set the context of the complex social fabric of the nation and the uneven and distorted development of the economy.

2 The Historical Context

DOI: 10.4324/9780429267987-2

The different peoples of modern Zambia have long and important, though separate, histories. Zambia was not a "nation" as defined by common language, kinship, political authority, or geographical distinctiveness until it was pieced together by British mercantile interests in the late nineteenth century. In the prior four centuries, the economic life of the region had been gradually reoriented to external markets. Yet the nation's ethnic groups lived in relative isolation, one from another. In the eighteenth century, those who controlled the external markets drained the region's wealth in the form of minerals, capital, and labor. Initially the foreign powers were Arab, Swahili, and Portuguese; later the British brought the area under direct colonial rule. The bulk of this chapter explores the era of British rule, broken into three separate periods extending from 1890 to 1963. A review of modern Zambian society, however, requires a brief survey first of the geography of the country and then of the precolonial histories of the peoples found within its modern territorial delimitations. Finally, the period of European penetration is examined in which to varying degrees, through different economic mechanisms and under different political dispositions, the modern Zambian political economy was oriented toward the external markets of the Western industrial states and South Africa.

GEOGRAPHY

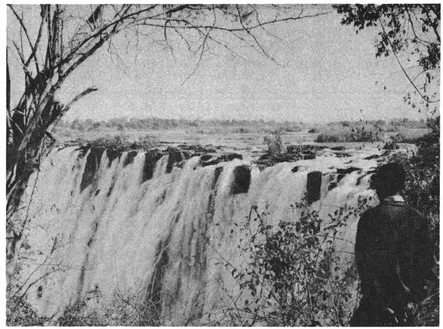

The resolution of European disputes over colonial boundaries in the late nineteenth century left Zambia with its modern butterfly shape, which encompasses two distinct wings of the country: the northwest, west, and south in one wing and the northeast and central areas in the other (see frontispiece). Despite this arbitrary division, most of the outlines of the country follow the geographical lay of the land. The Zambezi and Luapula rivers and lakes Mweru, Kariba, and Tanganyika all form international boundaries. Situated high on the great central African plateau, most of the land undulates at 4,000 feet above sea level. Beautiful waterfalls and river valleys cut into this plateau but are hidden far away from the main roads. The country is most famous for the spectacular Victoria Falls and the manmade Lake Kariba that divide present day Zambia and Zimbabwe (see Photos 2.1 and 2.2).

PHOTO 2.1 Victoria Falls.

A large wedge is sliced out of central Zambia. This is the Congo or Katanga Pedicle, product of an agreement struck among British and Belgian colonialists and private commercial speculators in the early years of the twentieth century. As a result, Zambia shares with Shaba Province of Zaire (formerly Katanga of the Congo) some of the richest copper- and cobalt-bearing ores in the world. Zambia's peculiar shape also means that the country has eight immediate neighbors—Zaire, Angola, Namibia (Southwest Africa), Botswana, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, and Malawi. The peoples of central Africa have been arbitrarily assigned to these different countries, and their long migrations have diminished, although not totally ended.1

HUMAN SETTLEMENT AND PRECOLONIAL HISTORY

Humans and their ancestors lived in central Africa close to half a million years ago. Archaeological digs at Kalambo Falls in the extreme northeast and Victoria Falls region in the south are rich with evidence of humans in...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents Page

- List of Illustrations and Tables Page

- Preface Page

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Historical Context

- 3 Society and Culture

- 4 The Political Economy of the First Republic, 1964-1972

- 5 The Political Economy in Decline, 1973-1985

- 6 Zambian Foreign Policy

- 7 Zambia's Future, Zambia's Choices

- Appendix A: Glossary

- Appendix Β: Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Zambia by Marcia Burdette in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & African Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.