Public Sector Leadership in Assessing and Addressing Risk

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Public Sector Leadership in Assessing and Addressing Risk

About this book

Public Sector Leadership in Assessing and Addressing Risk explores risk management in practice, taking a specific focus on the identification of risks in the European public sector while contextualising its Eurocentric analysis within a global setting.

The volume lays important groundwork for understanding the main philosophical premises of risk management. Navigating the text's philosophical underpinnings such as 'Risk Management is a misnomer', the editors provide deep insight into global, strategic, and operational risk management that will prove invaluable for any practitioner.

Providing high quality academic research, ESFIRM provides a platform for authors to explore, analyse and discuss current and new financial models and theories, and engage with innovative research on an international scale.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Section One

Context

Chapter One

Our Complex World

Abstract

Principles and Concepts

Complexity

- Adaptation and innovation are the two central responses that agents employ to address challenges (challenges including, of course, risks, uncertainties, the unknown, and emergent phenomena).

- The fundamental operational feature of CAS organisations is that all agents (employees, managers, etc.) have unfettered ability to work with all other agents in order to assess and address threats or opportunities. These interactions may be seen as unconfined individual actions but might also be conceived as operating within organisational systems.

- CAS feature local rules (called schema) that guide individual agent’s judgement, decision rules, and behaviour. By use of the term ‘local rules’ it is suggested that the system is not hierarchical, nor does it operate in a centralised fashion. Everyone has a role in adapting to new conditions, innovating when necessary, and otherwise monitoring for challenges to the system.

- Leaders in CAS have different roles. Two management scholars recently observed that leaders in CAS are expected to … ‘Facilitate … (b)oundary spanning, organizing and implementing aligned actions, promoting cross-functional training, joint planning and decision-making, deploying resources across units to foster interconnectivity’ (Uhl-Bien & Arena, 2018). This is sometimes called complexity leadership.

- It may sometimes be said that CAS are ‘naturally regulated’, by factors like gravity and biological constraints. In organisational systems, questions abound as to what structures may need to be built to acknowledge artificiality. In other words, naturally regulated CAS are regulated by natural laws, while organisations have to recognise that the ‘regulations’ that bind them must be imposed and managed by humans.

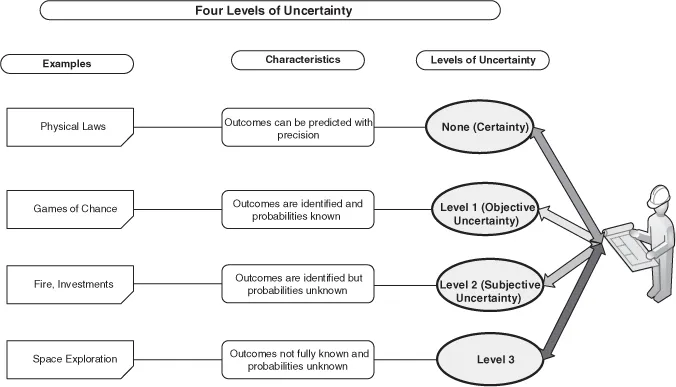

Uncertainty

Risk

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Section One. Context

- Section Two. Assessment and Analysis

- Section Three. Tools, Applications, Responses

- Section Four. Leading and Managing in an Uncertain World

- Index