![]()

Part I

Theory and Tradition

![]()

Chapter 1

Race and Culture; Ethnicity and Identity

The discourse around race and culture in the mental health field has undergone complicated manoeuvres over the past twenty years, bringing to prominence two ideas related to race and culture, namely ethnicity and identity. This chapter discusses all four concepts before exploring the meaning of ‘community’ in relation to the primary concepts of race and culture and examining racism both in historical and current perspectives, mainly from a practical point of view.

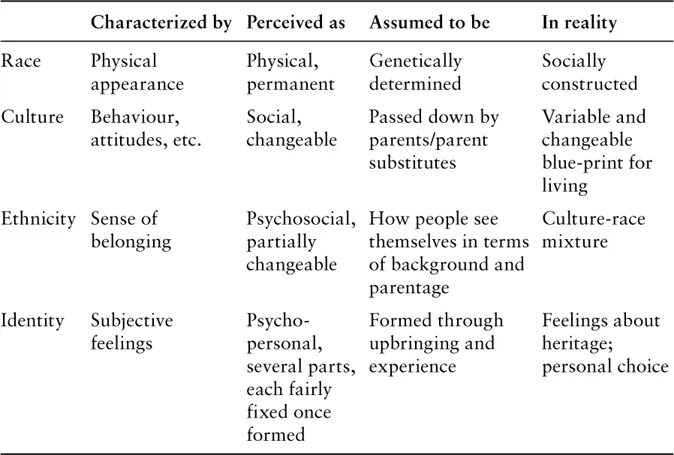

Table 1.1 summarizes popular perceptions and realities in the current socio-political scene in the UK. In short, race is perceived as physical, culture as sociological and ethnicity as psychosocial. Identity is different to all these in being an entirely subjective psycho-personal concept. But it should be noted that popular perceptions change; the description of terms in the table are merely guides to thinking about the concepts rather than strict definitions. A major problem arises from the conflation in popular perceptions of culture and race, discussed later as the muddle between race and culture.

Concept of ‘race’

The term ‘race’ entered the English language in the sixteenth century at a time in Europe when the Bible was accepted as the authority on human affairs; and it was used originally in the sense of lineage, supposedly ordained at the creation of the world (Banton, 1987). A rather vague racial awareness of, for example, Jews and Muslims as non-Christian ‘other’ evolved into the modern conception of race with the rise of European power and its conquest of the Americas (Banton, 1987). Major figures during the (European) ‘Enlightenment’, expounded racist opinions: ‘The numerous writings on race by Hume, Kant and Hegel played a strong role in articulating Europe’s sense not only of its cultural but also racial superiority … “reason” and “civilization” became almost synonymous with “white” people and northern Europe, while unreason and savagery were conveniently located among the non-whites, the “black”, the “red”, the “yellow”, outside Europe’ (Eze, 1997, p. 5). David Hume (born 1711, died 1776) reasoned that ‘there never was a civilized nation of any other complexion than white, nor even any individual eminent either in action or speculation. No ingenious manufactures amongst them, no arts, no sciences’. And Immanuel Kant (born 1724, died 1804) reasoned that the ‘difference between these two races [white and black] … appears to be as great in regard to mental capacities as in color’ (Eze, 1997, pp. 33–55).

Table 1.1 Race, culture, ethnicity and identity

Later, as Darwinian concepts were accepted in European thinking, race was seen as subspecies on the basis of which scientific racism developed (Chase, 1997; Graves, 2002); finally sociological theories of race led to the notion of races as populations, where ‘race’, a social concept rather than a biological one, continued to play a fundamental role in structuring the social world of humankind (Omi and Winant, 1994). Today, all these ideas exist together, giving rise to considerable confusion in current thinking about race since the corollaries of these various notions are very different. For example, race as lineage may be a satisfactory explanation of physical differentiation of populations that are relatively isolated from each other, but cannot interpret differentiation in an increasingly globalized ‘mixed’ world, except by assuming that ecological forces determine behaviour of human beings in the way they determine social life of domesticated animals whereby, for example, different breeds of dogs persist.

One consequence of the confusion about what is meant by ‘race’ is that two seemingly opposite tendencies are evident – ‘the temptation to think of race as essence, as something fixed concrete and objective … [or] as mere illusion, a purely ideological construct which some ideal non-racist social order would eliminate’. Both approaches are faulty. Racism continues to be a powerful force albeit in changing guises; biologically based human characteristics (‘phenotypes’) are invoked by the concept but these have been – and continue to be – selected by social and historical processes. So ‘race’ may be defined as ‘a concept which signifies and symbolizes social conflict and interests by referring to different types of human bodies’ (Omi and Winant, 1994, pp. 54–5, italics in original).

Culture

One of the original meanings of culture was husbandry – the verb ‘cultivate’ derives from this meaning. But over the years, culture has been transformed from being an activity to become an entity – almost an abstract concept. At one time ‘being cultured’ was synonymous with being civilized, but then anthropology, in association with nineteenth-century colonialism, gave culture its modern meaning of ‘a unique way of life’ (Eagleton, 2000, p. 26). During the past thirty years, ‘cultural studies’ have widened their scope to such an extent that the word culture has almost lost a specific meaning. This section will attempt to bring some coherence to its use with reference to the main subject of the book – mental health.

The term culture applied to an individual usually refers to a mixture of behaviour and cognition arising from ‘shared patterns of belief, feeling and adaptation which people carry in their minds’ (Leighton and Hughes, 1961, p. 447). The allusion to family culture or the cultures of whole communities or even nations extends the meaning of the word ‘culture’ further. Therefore, referring to a multiplicity of cultures – for example, in a multicultural society – implies differences between groups of people with different backgrounds, traditions and worldviews. Apart from the use of culture in this broad sense as a shorthand for a sort of explanation of the way people live, we often refer to cultures of institutions or occupations/professions – for example, to police canteen culture, the culture of psychiatry or social work. In all these situations, culture means the ethos or the intangible underlying determinants of people’s behaviour in a particular context. We could call these organizational cultures as distinct from culture as the way people live. Finally, we tend to speak of the cultures of people identifiable by particular characteristics such as age (e.g., youth culture), experience (e.g., culture of the aristocracy, the oppressed, the poor) or some habit or predilection (e.g., drug culture, gun culture, paedophile culture). We can call these experiential/situational cultures.

Culture as the way people live

Here culture refers to a way of life common to a group which may or may not be defined as a ‘community’ (see later for discussion of community). It represents conceptual structures that determine the total reality of life within which people live and die, and of social institutions such as the family, the village and so on. It may go on to subsume all features of a person’s environment and upbringing, but specifically refers to the non-material aspects of everything that they hold in common with other individuals forming a social group – child-rearing habits, family systems, and ethical values or attitudes common to a group. In anthropological literature, the idea of culture as a body of knowledge held within a group (Goodenough, 1957) gave way to culture as ‘something out there’, a social concept, and later as something ‘inside’ a person – a psychological state (D’Andrade, 1984, p. 91).

The past thirty years have seen major changes in the way culture is applied to the way people live and behave. First, following on the writings of Foucault (1967, 1977, 1988), there was an increasing awareness of the relationship between discourse – fields of knowledge, statements and practice, including those in medical, psychiatric and psychological practice – and power. Hence, categories which lump peoples or experiences together have become suspect. Second, the idea of culture as something that individuals or groups take on passively has been superseded by the idea of culture being made by people, both as individuals and groups – cultures as ‘products of human volition, desires and powers’ (Baumann, 1996, p. 31). In fact, culture is beginning to resemble its original meaning as husbandry.

Since the late twentieth century, culture is understood on a postmodern terrain as something variable and relative depending on historical and political viewpoints in a context of power relationships. The Location of Culture (bhabha, 1994) emphasizes the hybridity of cultural forms and behaviour in today’s world; Culture and Imperialism (Said, 1994) unravels the intimate connections between the understandings of culture presented in Anglo-American literature and European domination – nowadays called globalization. Culture is seen now as something that cannot be clearly defined, as something living, dynamic and changing – a flexible system of values and worldviews that people live by, and through which they define identities and negotiate their lives. Although this postmodern concept of culture cannot be captured properly in terms of polarities such as East and West, or traditional and modern, it is the view of the author that broad categories, such as Eastern, Western, Asian, African and European, have to be constructed and used in the interests of brevity, not in a reductionist frame of reference but in order to clarify what culture means in practical terms. Hence, these rough categorizations are used in discussing cultural variations throughout the book.

Organizational cultures

The report of the inquiry into the way the Metropolitan Police dealt with a racist murder in 1993 (Home Department, 1999) referred to racist attitudes that underpinned police activity as institutional racism defined in the report as:

The collective failure of an organisation to provide an appropriate and professional service to people because of their colour, culture or ethnic origin. It can be seen or detected in processes, attitudes and behaviour which amounts to discrimination through unwitting prejudice, ignorance, thoughtlessness and racist stereotyping which disadvantages minority ethnic people. (p. 28)

Since the report came out, there has been considerable argument as to whether Macpherson, the Chairman of the Inquiry, pointed to the culture of the Metropolitan Police as racist or just to racist attitudes within it. For many years the mental health system itself has been hailed as institutionally racist (discussed further in Chapter 4) and the question arises as to whether the culture of psychiatry is racist – the term culture being used as indicative of the ethos of the discipline. This is a loose use of the word; speaking more strictly, it is preferable to limit the term culture to describe a way of thinking or operating that emanates from, or is created by, a group of people working in fairly close association with each other. A situation in other words that gives rise to a more-or-less common way of doing things by people adhering to a tradition, acting in unison for a particular purpose. So racist attitudes within a system may, if pervasive among the group, constitute a racist culture. In other words, it is necessary to be careful in speaking of culture in relation to organizations or systems. Culture is about people not about bricks and mortar, even when attached as an adjective to the words ‘institution’ or ‘system’.

In a study of black people’s experience of being compulsorily detained under the Mental Health Act, Browne (1997) found that although social workers knew that racist stereotyping of black people as dangerous was a major factor in police involvement in the admission of black people, this bit of information, usually handed out during training and accepted by social workers as valid, had no effect on their day-to-day activities. It could be reasonably deduced that the culture of social work practice in the area that Browne researched was racist although the culture of the system of training may well have been anti-racist. The underlying ethos of the system as a team or group of people working together had perhaps negated the effect of training. But the research quoted did not mean that all social workers behaved in this way or that social work practice as a whole was racist; social workers do not work as a whole, they work in teams or as individuals.

Consider now the training of professionals as a system of training. In the case of psychiatrists, training is overseen by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, through committees under its Dean. Training systems throughout the country are examined by the College although organization of training at grass roots is left to tutors in each training site. It would be accurate to speak of a culture of psychiatric training, seeing the training system as an organization, because there is a particular way of doing things that is promoted across all training. It is well known that psychiatric training perpetuates biomedical ways of diagnosis and treatment; social perspectives and ideas of health and illness inherent in non-western systems of medicine such as Ayurveda are not included in the training. In such a situation, one could say that there is a culture of training that is at least ethnocentric, possibly racist, in being oblivious to ways of thinking that are not derived from western traditions.

Situational/experiential cultures

The concept of culture applied to people who are grouped together for no other reason than their age or predilection to indulge in some habit is of dubious validity or usefulness. Consider the term ‘youth culture’. Clearly young people may show similar types of behaviour because they are passing through similar experiences, especially if they are (say) from similar backgrounds. But unless they are involved with each other as people, for example, by being members of groups such as ‘gangs’, social clubs or sports teams, it is misleading to attribute a ‘culture’ to them, however similar their behaviour, views or appearance as individuals may be. Admittedly, people who use drugs or resort to using guns may well associate with one another because they have to procure their supplies (of drugs or guns) through centres or agents, or live in a particular part of a city. In doing so, they may form personal links and develop a common way of seeing the world, behaving, and so on, in which case they may be properly seen as having a culture. But if this is not the case, it would be incorrect to attribute ‘culture’ to a class of people merely because they use illegal drugs or guns.

Muddle between race and culture

It would be seen from earlier paragraphs that the term ‘culture’ lacks precision and its meaning is both variable and dynamic. As a result, culture is often confused with race. The question on ethnicity in the British Census (2001) under the heading ‘What is your ethnic group?’ asked about cultural background not ‘race’ reflecting this on-going confusion. And national statistics about ethnic groups are interpreted both as differences in culture and differences in ‘race’ – something that may be used to promote racist political propaganda. In the public media, people seen as being racially different are assumed to have different cultures; and value judgements attached to ‘race’ are transferred to culture. Another problem is that when people are identified in ethnic terms – ethnicity containing both cultural and racial connotations that are not clearly differentiated – there may be a tendency to impose culture on people because of the way they look (‘racially’) instead of allowing people to find their own position in the stream of changing and varied cultural forms. This creates resentment against the concept of multiculturalism itself. Even more importantly, some aspect of culture, like religion, may be taken as a marker of racial difference in the way Jews – and more recently Muslims – are sometimes seen as belonging to a specific ‘race’.

Another problem that arises from this muddle between the understandings of race and culture is that ethnic designations (at least in the UK) are seen as concerning non-white people alone; cultural diversity remains a minority issue; and a multicultural society is a place where minority issues are given primacy. To complicate the race and culture discourse even further, racism undermines multiculturalism by introducing the idea, not necessarily expressed openly, that cultures are on a hierarchy of sophistication, some being less ‘developed’ than others, feeding on the negative aspects of a discourse where industrially underdeveloped or developing countries are seen as ‘primitive’ in all respects, including their cultures.

Ethnicity

Ethnicity overlaps in meaning with both race and culture, encompassing both, yet the common features of people in an ethnic group are often not clear-cut in terms of physical appearance (race) or social similarity (culture) alone or in combination. Subjective feelings too come into play represented by a sense of belonging to a group – an ethnic group – where cultural or racial similarity, real or imagined, plays a part. Yet, this sense of belonging may well arise not because of self-perception but because of the way ot...