![]()

chapter 1

Social Work Practice and the Law

In this chapter, you will learn about:

■ The organizational and administrative framework

■ Community care services

■ Directions and guidance

■ Powers and duties

■ Human Rights Act 1998

■ Anti-discrimination

■ Director of Social Services

■ Social work practice and the law

■ Delegated and designated functions

■ Registration of social workers

■ Standards of proficiency

■ Partnership and coordination

■ Accountability

■ Conclusion

Remember to consult The Legal Toolbox on pp. xiii–xx. This will help you to understand processes and procedures referred to in this chapter.

Introduction

Social work law is the basis of social work practice. It determines the organizational setting in which social work takes place; it defines what social workers are employed to do; and, by setting out what redress is available when things go wrong, it determines the boundaries of social work action and the nature and extent of social work accountability. It is the law that defines the individuals towards whom social workers have responsibilities, such as, vulnerable adults and their carers, and which determines, often in broad terms, the nature and extent of social work intervention (such as prevention, protection and rehabilitation). The law also sets out the conditions under which compulsory intervention is permissible, as well as the safeguards that should ensure that such intervention takes place in accordance with due process and in adherence to human rights. An important aspect of the social work task is to determine appropriate levels of support, care, protection and control, taking into account the inevitable constraints imposed by the availability of resources. It is the law, too, that identifies the strategic aims and objectives that underpin the delivery of services, both nationally and locally. In essence, social work law consists of three elements: a set of organizational and administrative processes and procedures; a specific body of statutes and judicial decisions; and a body of professional ethics and values. The law provides ‘the essential bone structure of social work practice’ (Roberts and Preston-Shoot 2000) and so helps to determine its nature and character.

Table 1.1 Number of clients receiving community-based services by type

| 18–64 | 65 and over |

Day care | 77,000 | 83,000 |

Direct payments | 78,000 | 61,000 |

Equipment and adaptations | 100,000 | 330,000 |

Home care | 103,000 | 415,000 |

Meals | 4,000 | 56,000 |

Other | 5,000 | 62,000 |

Professional support | 166,000 | 102,000 |

Short-term residential (not respite) | 13,000 | 57,000 |

Source: Health and Social Care Information Centre (2013a).

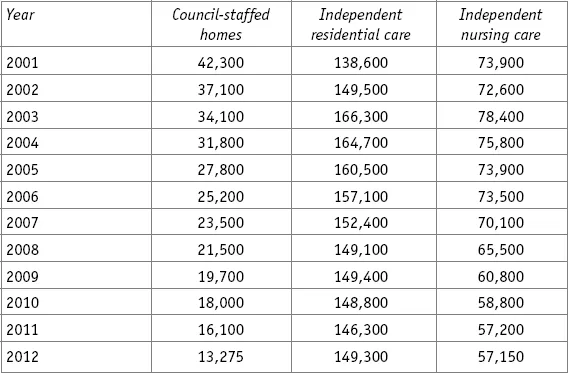

Table 1.2 Number of people in residential and nursing care by type of accommodation

Source: Health and Social Care Information Centre (2013a).

Significant numbers of people rely on social services, either partially or completely. For example, Tables 1.1 and 1.2 present the number of people receiving domiciliary and residential/nursing care.

Given these numbers, it is crucial that social workers understand the nature and extent of their legal mandate, and how it affects the lives of those who need their help or support.

The organizational and administrative framework

The administrative and organizational framework for the delivery of social services is to be found mainly in the Local Authority Social Services Act 2000 (LASSA 1970), as amended, and the Local Government Act 2000 (LGA 2000).

The law recognizes the concept of an artificial legal person created by an Act of Parliament. Legal persons of this kind are collectively known as ‘corporations’, of which local authorities are an important example. As such, local authorities are capable of assuming legal powers and responsibilities to enable them to provide or arrange a range of services in their locality. The structure of local government in England is complex and varied. However, s.1 LASSA 1970, identifies the units of local government with legal responsibility for providing or arranging social services in their area. These consist currently of the metropolitan districts (such as Sheffield and Wolverhampton) and the London boroughs (such as Wandsworth and Brent, and the City of London Council); the county councils (such as, Lancashire and Kent); and the unitary authorities (such as Cornwall and Shropshire) (s.1 LASSA 1970, as amended). For ease of reference, these will be referred to as Councils with Social Services Responsibilities (CSSR). The LGA 2000 requires such authorities to set up an executive structure with decision-making powers and responsibilities, including the provision of social services that are required to undertaken under s.1A LASSA 1970. The Secretary of State may designate other social services functions to be performed by these local authorities.

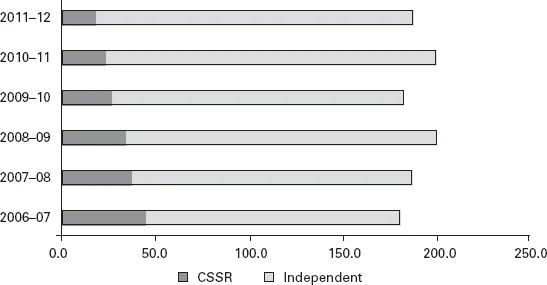

A significant feature of the development of social services over the past few years has been the increased involvement of the independent sector in the provision of services; that is, profit-making organizations, as well as voluntary organizations. The Griffiths Report and the subsequent National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990 (NHSCCA 1990) developed a more open market for the provision of community care and residential care for adults (Griffiths 1988). Table 1.2 shows that residential care provided directly by local authorities represents a small proportion of the total provision. As Figure 1.1 shows, for domiciliary care the major provider is the independent sector.

Figure 1.1 Contact hours in millions for home care provided during the year, by sector, 2006–07 to 2011–12

Source: Health and Social Care Information Centre (2013a).

Exercise 1.1

Choose a local authority with social services responsibility and identify the following characteristics:

■ The demography of the local authority area (structure of population: age, disability, gender, ethnicity, etc.) and its economic profile (e.g. unemployment levels, social housing, and indicators of deprivation).

■ The level of expenditure on social services for the area and how it is distributed between various groups (e.g. children, older people, mental health, learning disability).

Much of this data should be available on the authority’s website.

1. Do you consider this information is easily accessible to members of the public?

2. Are there any gaps in the information provided by the authority?

Community care services

As defined in s.46(3) NHSCCA 1990, ‘community care services’ for adults are services that a local authority may provide or arrange to be provided in its area under:

■ ss.21–29, Part III, National Assistance Act 1948.

■ s.45 Health Services and Public Health Act 1968.

■ s.254 and Schedule 20 National Health Service Act 2006.

■ s.117 Mental Health Act 1983.

Since the NHSCCA 1990, further legislation has come into force (such as the Equality Act 2010 (EA 2010) plus no fewer than three separate enactments relating to carers). These are discussed in the chapters that follow.

Directions and guidance

Much of the legislation concerning services for adults is set out in very general terms. More detailed provisions have been issued by the Department of Health in the form of Directions and Regulations and, exceptionally, in the form of Circulars. As long as they are properly made and issued, such documents often have, in practice, the same legal effect as the original legislation. They are open to challenge only if their contents are inconsistent with the terms of the original legislation, or the Human Rights Act 1998 (HRA 1998).

Another means by which gaps in the legislation are filled is through guidance issued by the Department of Health. Section 7 LASSA 1970, states that:

| “ | Local authorities shall, in the exercise of their social services functions, including the exercise of any discretion conferred by any relevant enactment, act under the general guidance of the Secretary of State. |

As will become apparent later in the book, a substantial amount of s.7 guidance has been issued. What is its legal significance? (See Box 1.1.)

The consequence of not following s.7 guidance is...