![]()

PART I

RESILIENCE:

THE CONSTRUCT

![]()

CHAPTER 1

Resilience – An Introduction

Introduction

‘Resilience’ is a word that one hears often but which often seems to defy a precise definition. In the context of this text, ‘resilience’ encompasses psychology, sociology and child and adolescent development to describe children and young people who flourish despite what can objectively be described as very difficult circumstances.

It is common to assume that children and young people are more likely to show strong negative reactions if they have been subjected to neglect or abuse during early childhood. It is also assumed that they are more likely to develop problems in subsequent life. However, research shows that not all do (Garmezy et al., 1984; Masten et al., 1990). Some children do not appear to be significantly damaged by their challenging backgrounds, and some even thrive; these children are considered to be resilient.

Although many studies have focused on children and young people growing up with varying degrees of dysfunction and/or deprivation, children in affluent and apparently ideal circumstances can also face challenges to resilience. Indeed, the concept of resilience can also be applied to those who do well despite not being exposed to significant personal difficulties.

The rationale for building resilience in children and young people is that, irrespective of background and or early experience, those who develop appropriate skills and competence will be able to cope constructively with challenges and difficulties that they encounter daily and will develop levels of resilience that could help them as adults. The modern social construction of resilience gives authority to the promise that, with the appropriate skills and capabilities, children and young people will develop into successful adults who will be able to steer a positive life course for themselves, their families, their communities and to the benefit of the state (Rutter, 1984). This is a promise that children and young people can emerge from a stressful childhood or traumatic period with strong personal strength – even made stronger in some cases – by the very difficult circumstances that they have lived through.

The acquisition of resilience in childhood is a promise of a successful future. Fostering qualities of resilience in children throughout childhood has the potential to benefit not only individuals and their families but also entire communities and society at large. In effect, resilience conveys the promise that children and young people can, despite inauspicious beginnings, become positively engaging adult citizens rather than suffering the long-term negative effects of adverse life circumstances. Even in lives that are objectively very difficult, the promise of resilience can often be envisioned as a beacon of hope.

Over the last 50 years, there has been extensive research and commentary on the components, characteristics and practice of building resilience. There is now no longer any doubt that the skills of resilience are important to children and adults. However, differences in the trajectories of diverse individuals in response to adversity provide a varied canvas for the study of both the construction and the determinants of resilience.

The literature on resilience spans a wide range of definitions, approaches and determinants. This chapter explores these definitions of, approaches to and determinants of resilience, and examines how these contribute to our understanding of the skills and competencies commonly associated with the building of resilience during childhood and adolescence.

The construction of resilience

The meaning of the term ‘resilience’ is not straightforward. It is commonly used to describe a variety of positive attributes and successes. Firstly, it may be a description of a collection of characteristics that children or young people may exhibit despite having experienced significant disadvantage in their earlier years. Thus, in this sense, resilience refers to better than expected emotional and developmental outcomes. Secondly, resilience may refer to young people having high levels of competence even when they have been exposed to high levels of stress when dealing with threats to their well-being. And thirdly, resilience may refer to positive functioning that indicates recovery from trauma.

A number of influential definitions (Box 1.1) have emerged from various disciplines and from research carried out in a variety of settings and life circumstances.

Box 1.1 Definitions of resilience

1. Resilience is a dynamic process when there is a threat to the child’s well-being and the child demonstrates positive adaptation. Children deal with stress at a time and in a manner that allows them to develop their qualities of self-confidence and social competence (Rutter, 1971).

2. Resilience is a process and not a fixed quality. It is seen in the successive positive adaptations of those who are exposed to adversity (Masten et al., 1990).

3. Resilience comprises a set of qualities that help one to deal with or overcome a lot of the negative impacts of adversity in life (Gilligan, 2000).

4. Resilience is the compound of personal, cultural and environmental factors that combine to make it easier for the individual to navigate difficult periods in life and do well (Ungar, 2008).

5. Resilience evokes relatively good outcomes in the face of adversity, facilitated by personal qualities such as self-efficacy, secure attachments and good relationships, and resources within the family and in the broader community (Daniel, 2010).

Whether one understands resilience as positive developmental outcomes, a set of competencies, or as coping strategies, the presence of resilience is associated with positive functioning and positive lifestyles for children, young people and their families. These conceptualisations of resilience share the notion that resilience is influenced by a child’s environment and that the interaction between individuals and their social ecologies will determine the degree of positive outcomes experienced.

Recent trends in research have moved the debate from the ‘what’ to the ‘how’ – how do resilience factors lead to positive outcomes, and what mechanisms are involved? These definitions also emphasise an understanding of resilience as a process rather than as a set of individual character traits. However, processes for developing resilience are complicated. Every successful young person may take a different path or trajectory.

Rutter (1999, 120) suggests that for resilience to have any meaning, it must also apply to differences in responses to a given dose of the risk factor and that it must be acknowledged that individuals will have different trajectories in response to adversity. For Rutter, these differences are important and, in effect, provide the infrastructure for the study of resilience. This view of resilience as a dynamic process has itself generated a number of perspectives on the methods and processes of adaptations that may or may not result in promoting features of resilience within the child, family and community contexts.

The concept of resilience has emerged most strongly over the last 50 years. On one hand, resilience has developed as an academic construct through sustained research and scholarly activity. On the other hand, resilience as a concept has caught the imaginations of the political and professional classes. The result has been the emergence of perspectives, approaches, interpretations and expectations. For many, resilience is perceived less as discovered knowledge and more as individual constructions of models and schemas.

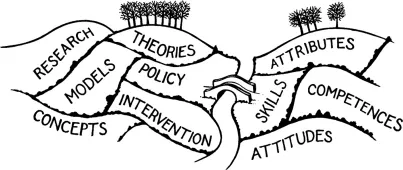

This conceptual framework of resilience is based on two interacting features – the conceptual foundations of resilience (the left side of the framework) and the personal resources and assets (the right side of the framework) – with the ability to cycle back and forth from right to left and vice versa. In this model, resilience has been constructed against a backdrop of academic research and presents a flexible framework that can be applied to different contexts and can facilitate different trajectories towards resilience (Figure 1.1). Figure 1.1 presents a portrait construction wherein either side may vary according to factors that underpin and/or drive an individual’s pace and trajectories.

The construction of resilience is presented here as one that can fluctuate and can be strengthened or weakened by different actions and interactions as well as experiences and practices. Resilience as an asset depends on its particular context, interactions and resources for change. The promise of resilience is its potential as a mechanism for positive citizenship into the twenty-first century – a citizenship permeated with sustainable, personal, cultural and social values (see Chapter 9). Cultural factors play a significant role in determining the legitimacy of the construct while individual factors govern the form and characteristics of resilience (Ungar, 2008). Figure 1.1 provides a framework wherein political, cultural, social and economic policies and factors can shape complex understanding of resilience at an individual level.

Figure 1.1 The construction of resilience

Vignette 1.1

Monica is a young woman who lives in a farming community in the US. She is very close to her paternal grandmother, who lives close by. Her father was an alcoholic, and when he was drunk – which was most days – was abusive to her mother, Monica and her two younger brothers. Monica was 11 years old when her father left home and never came back. Monica helped her grandmother come to terms with this loss. Home life became better for a short time, and Monica was able to begin to enjoy sports – she joined a basketball team and became an athlete in track and field. However, her mother’s partner, Tom, moved into the family home six months ago. Monica does not like her mother’s partner, and there are constant rows between Monica and her mother and Tom. Monica became angry that her life had changed again and started drinking in high school. However, she continued with her sports to spite Tom, who kept telling her that she should be at home looking after her two brothers. She continued to live at home but had very little interaction with her mother and drifted away from family activities. In her third year of college, her drinking became out of control, and she was expelled. Her drinking continued and she moved in and out of low-paid work. She recently got a job at a local gym (as an assistant) and is desperate to keep this job and to go back to college – but she continues to drink.

Jenny lived in South London in a block of flats with her family. Jenny was always closer to her father than to her mother, but her father died suddenly when she was 11 years old. She felt the loss of her dad very deeply and felt lonely and left out because she believed that her mother preferred her younger sister. Her mother married again, but Jenny hated being around her mother and her new husband, as they would make explicit sexual references about her, such as ‘Hey, Jenny, you look very sexy tonight’. As an adolescent she began to do very badly in school and to lose interest in her studies. When she was 14, she ran away from home and lived on the streets for two years, with no contact with her family. During that time, she worked as a sex worker and regularly presented for emergency contraception. Recently Jenny has got a couple of low-paid cleaning jobs. She is now 16 and hates her life but continues to have no contact with her family and has no friends her own age. She has now approached the Salvation Army to ask for help to find somewhere to live near her cleaning jobs.

Discussion

With reference to Figure 1.1, consider the two case studies in the vignette and answer the following questions.

1. Compare the different personal resources and assets available to the adolescent in each case.

2. Explore the different external factors that may help or hinder recovery in each case.

Approaches to resilience

Recognising the building of resilience as an interpretative and constructed process leads to recognising childhood as (i) having the rudimentary beginnings of resilience and (ii) having the potential to develop these fledgling beginnings into adept realisations. In essence, this forms the basis for understanding how resilience can be developed and fostered during childhood and into adulthood. An analysis of approaches to and perspectives of resilience provides an opportunity to critically explore the matrix of factors that constitutes the shaping of resilience through childhood.

Behavioural and adaptation perspectives

Olsson et al. (2003) identify two different approaches to resilience, the differences between which are not always clear, and considerable confusion can arise as they are often used interchangeably:

1. a behavioural approach – defined as an outcome charact...