Introduction

There is no better way to introduce this book than to turn directly to its main subject—women and their economic lives. It is certainly no secret that women’s lives have changed enormously over the course of the twentieth century and the first few decades of the twenty-first century. This change is especially obvious in the subject matter of this text—family, work, and pay.

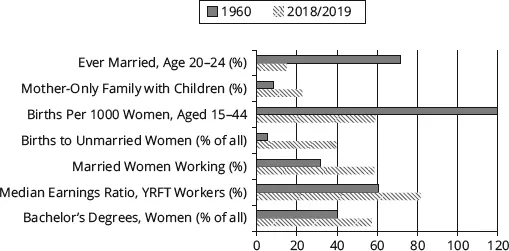

Figure 1.1 shows some of the major changes in marriage, fertility, education, work, and pay for women that occurred between 1960 and the late 2010s in the United States.

In 1960, women’s choices and opportunities concerning fertility, marriage, education, and occupation were very different than they are today. Early marriage was the norm: more than 70 percent of women age 20–24 were currently married or had been previously married. Fertility was very high; there were about 120 births for every 1,000 women age 15–44, which works out to more than 3.5 births per woman over her lifetime. The married-couple family was by far the dominant adult family structure; only 8 percent of families with children were headed by a single woman. Almost all births occurred within marriage; only 5 percent of births were to unmarried women. A married woman’s place was in the home, and that is where she spent most of her adult life. Just barely over 30 percent of all married women worked, and only 20 percent of married women with young children did. Many older married women had never worked for pay since their wedding day or shortly thereafter. A woman with earnings at the median earned only about 60 percent of her male counterpart’s earnings, even when she worked year-round full-time (YRFT in the table). Women earned only 40 percent of undergraduate degrees at colleges and universities.

By the late 2010s things have changed substantially. Later marriage is now the norm, with just 15 percent of women now ever-married at ages 20–24. Fertility has fallen sharply to about half its I960 level, the lowest rate ever recorded in the United States. The link between marriage and fertility has weakened. Births to unmarried women have grown and are now more than 40 percent of all births; consequently, the proportion of families with children that are headed by a single mother has nearly tripled to 23 percent. Married women have joined the workforce in record numbers, and now nearly 60 percent are working. Many younger married women have worked nearly every year since their wedding day, barely leaving the labor force even to have a family. Women now are more likely to attend colleges and universities than men are. Women still earn considerably less than men, but the median earnings ratio for YRFT workers has increased more than 20 percentage points.

The same trends have been seen throughout most of the rest of the world. Over the same time period, the labor force participation rate for women rose by 20 percentage points or more in much of Europe. Fertility has halved, falling from a world average of nearly five births per woman to just under 2.5. Fertility is falling even in the poorest, least developed countries in the world; in India, births per woman fell by over 50 percent from nearly 6 to under 2.5; and in China, home of the “one-child policy” (which was lifted in 2016), fertility fell from about 5 to 1.6. In many European countries, births per woman are well below replacement rates, and if those rates are maintained for several generations, total population will actually fall. The gender earnings ratio increased between 1975 and 2018, by about 9.8 percentage points in Australia, 17.8 points in Japan, and 23.6 points in the United Kingdom. Marriage rates have fallen in most developed countries; they are about one-third lower in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries than in 1970.

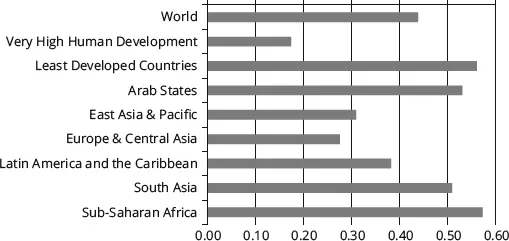

Despite these trends, we are still far from gender equality. The United Nations (UN) measures gender inequality on a global basis by the Gender Inequality Index (GII). The GII measures the extent of gender inequality using three broad factors: women’s reproductive health status, measured by maternal mortality and adolescent fertility; women’s empowerment, measured by their educational attainment relative to men and their political representation; and women’s labor market participation relative to men’s. The index is scaled from 0 to 1, where 0 means that men and women fare equally and 1 means they fare as poorly as possible in all dimensions. The UN interprets the measure as the percentage loss to potential human development due to gender inequality.

The measure is certainly imperfect in many ways. It is constrained by the availability of data that are reliable and comparable across countries. For example, the UN notes that the index does not include measures of women’s earnings relative to men’s, of their non-market work in the household, and of their ownership of assets. Political representation is based solely on a country’s national parliament and thus ignores women’s participation at local and regional levels. And there is no perfect way to combine a group of elements into a single composite measure. How much weight should each one have? Should they be equal? Or are some elements more important than others? Still, the GII is useful and informative.

The most recent GII data are for 2018, when Switzerland had the best (lowest) score of 0.037, closely followed by Denmark and Sweden (tied for second place), the Netherlands, Norway, Belgium, and Finland. All of the countries in the top nine are European, including all of Scandinavia. The highest-ranking non-European countries were South Korea (10th), Singapore (11th), and Israel (24th). At the bottom of the ranking was Yemen, followed by Papua New Guinea, Chad, and Mali; these countries have GII scores of 0.68 and higher. These countries had maternal mortality and adolescent fertility rates that were 20–40 times higher than those in the top group of countries, and also very large gender differences in education and labor force activity. The United States was just 42nd, with a GII score of 0.182. The low US ranking reflects its relatively high rates of maternal mortality and adolescent fertility—four to six times those of the top-ranked countries—and its relatively low female participation in government. France ranked 8th, Japan 23rd, the United Kingdom 27th, and China 39th.

Figure 1.2 shows the variation in the GII across broad geographic regions. For the world as a whole, the GII is 0.439, while in countries designated as Very High Human Development,1 it is 0.175, which is still far from equality. The Least Developed Countries and Sub-Saharan Africa have the highest GII values, with Arab states and South Asia also conspicuously high. All four of those groups have a GII value above 0.50. East Asia and the Pacific countries and Europe and Central Asia have lower values, reflecting greater gender equality.

Why study women?

Why is there a separate economics course and textbook on women in the first place? After all, most universities do not offer an economics course on men. There are quite a few good reasons. First, many courses in economics are male-oriented, even when they do not explicitly say so. For example, some of the topics discussed in this book are parts of standard non-gendered courses in economics. Labor supply analysis is an important part of courses in labor economics, but those courses almost always emphasize a model of behavior that fits men’s choices well, but totally misses the mark on women’s choices—often without ever saying that this is so. For example, as is explained more thoroughly in Chapter 8, the standard labor supply model considers an individual who chooses between market work and leisure, thereby excluding from the analysis the activity that has occupied much of women’s time for generations—namely, family responsibilities (which we will later analyze by the more formal name “household production”). By incorporating this extra dimension, the analysis in this book provides a much richer framework. In the process, it enables us to make sense of the incredible increase in women’s labor force activity over the course of the last century, something that is impossible to do using the standard (male) labor supply model. In much of the economics curriculum, women are invisible. In this book, they are very visible.

Second, women are, frankly, more interesting from an economic standpoint than men. The many changes in women’s lives that we saw in Figure 1.1 are great material for economic analysis. In contrast, men’s economic lives have not changed nearly as much. Furthermore, women’s economic behavior, especially their participation in the labor force, is still more varied than men’s, so again, additional analysis is important and interesting. Studying women’s economic behavior also provides a natural link to interesting public policy issues, especially those relating to family and work. A consistent focus on women helps tie many interesting issues together.

Third, the major topics in this book provide a great opportunity to learn economics, precisely because they sometimes seem so far afield from traditional economics. At first glance, many of the items shown in Figure 1.1, especially marriage and fertility, are more like the topics traditionally studied in sociology. They may sound less rigorous than the usual fare in economics courses. Make no mistake, though—this is a course in economics.

The approach we use to examine these topics is utterly different from the approach that would be taken in almost any another discipline. We hope to convince you that economic analysis has a great deal to contribute to the understanding of these topics. Why have marriage rates fallen? Why did fertility decline? Why are more married women working? Why have earnings for women increased relative to men yet remain stubbornly lower? What economic forces were at work in all these changes? The process of thinking about these questions will surely provide a broader understanding of just what economics is.

Fourth, the issues discussed in this book are personal in a way that economics often is not. This book is not “X-rated,” but it does include adult discussions of marriage, children, and, yes, sex and contraception. The major topics of this book— family and work—are central features of virtually every adult’s life. They affect most of us more immediately and more directly than do some of the traditional topics of economics—monopoly versus competition, the benefits of international trade, and the economics of pollution, to name just a few. Those topics are tremendously important, but they are more abstract and often not part of an individual’s daily life in the tangible way that family life is. Thinking analytically—thinking like an economist—about personal issues is fun in a crazy kind of way. We know from personal experience that students learn more about economics when ...