![]()

MANAGING CHANGE: A PROCESS PERSPECTIVE

Introduction to Part I

Part I introduces the process theories of change that provide the conceptual framework for the discussion of the theory and practice of change management presented in Parts II to VIII.

Chapter 1 Process models of change

Chapter 1 introduces four process theories: teleological, dialectical, life cycle and evolutionary. All four view change as a series of interconnected events, decisions and actions, but they differ in terms of the degree to which they present change as a necessary sequence of stages and the extent to which the direction of change is constructed or predetermined.

Life cycle and evolutionary theories present change as a predetermined process that unfolds over time in a prespecified direction. Teleological and dialectical theories, on the other hand, view change trajectories as constructed, in the sense that goals, and the steps taken to achieve goals, can be changed at the will of (at least some of) those involved in the process. However, this may not always be easy to achieve in practice because those involved, especially those leading the change, may fail to recognize some of the dynamics that affect outcomes.

Attention is given to the impact of reactive and self-reinforcing sequences:

•Reactive sequences: When change involves different individuals and groups each seeking to pursue their own interests, then, depending on the balance of power, reactive sequences are likely to emerge and one party may challenge another party’s attempt to secure a particular outcome. Negative reactions may produce only minor deviations from the intended path or they may be so strong that they may delay, transform or block the change. Those leading change can improve their effectiveness by scanning their environment for threats and anticipating resistance or responding quickly when others fail to support their actions.

•Self-reinforcing sequences: When a decision or action produces positive feedback, it reinforces earlier events and this reinforcement induces further movement in the same direction. While self-reinforcing sequences can deliver benefits over the short term, change managers need to be alert to the possibility that they may divert their attention away from alternative ways of responding to situations, narrow their options, and lock them into a path that may deliver suboptimal outcomes over the longer term.

In order to minimize any negative impact from reactive and self-reinforcing sequences, those leading change need to be able to step back and observe what is going on, including their own and others’ behaviour, identify critical junctures and subsequent patterns – some of which may be difficult to discern – and explore alternative ways of acting that might deliver superior outcomes.

Chapter 2 Leading change: a process perspective

Chapter 2 builds on the ideas discussed in Chapter 1 and offers a process model of change based on teleological and dialectical theories. It provides a conceptual framework that those leading change can use to identify the issues they need to address if they are to secure desired outcomes. It can also be used to identify the kinds of questions that will help them reflect on how well they are doing and what else they could do to improve performance.

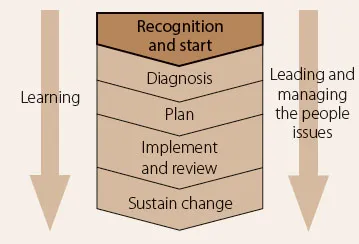

The model conceptualizes the management of change as a purposeful, constructed but often contested process that involves attending to seven core activities:

1recognizing the need for change and starting the change process

2diagnosing what needs to be changed and formulating a vision of a preferred future state

3planning how to intervene in order to achieve the desired change

4implementing plans and reviewing progress

5sustaining the change

6leading and managing the people issues

7learning.

These activities are presented as separate elements of the change process, because the decisions and actions associated with them tend to dominate at different points and there is a logical sequence connecting them. However, in practice, the boundaries are not always clear-cut. For example, the recognition of a need for change is based on an initial diagnosis of the situation, and attempts to implement plans for change that lead to unintended consequences also contribute to an unfolding diagnosis. Also, the sequence of elements specified in the model is not linear. It is often iterative, with some issues (such as diagnosis) being addressed more than once. Some issues can also be addressed simultaneously with others. For example, learning can occur at any or every point in the process and people issues need to be addressed throughout. This said, all the activities, such as diagnosis, planning and implementing, are important and need to be attended to by those leading a change.

When managing change is viewed as a process and events, decisions, actions and reactions are seen to be connected, those leading the change are more likely to be able to take action and intervene in ways that can break inefficient patterns and move the change process in a direction that is more likely to deliver superior outcomes.

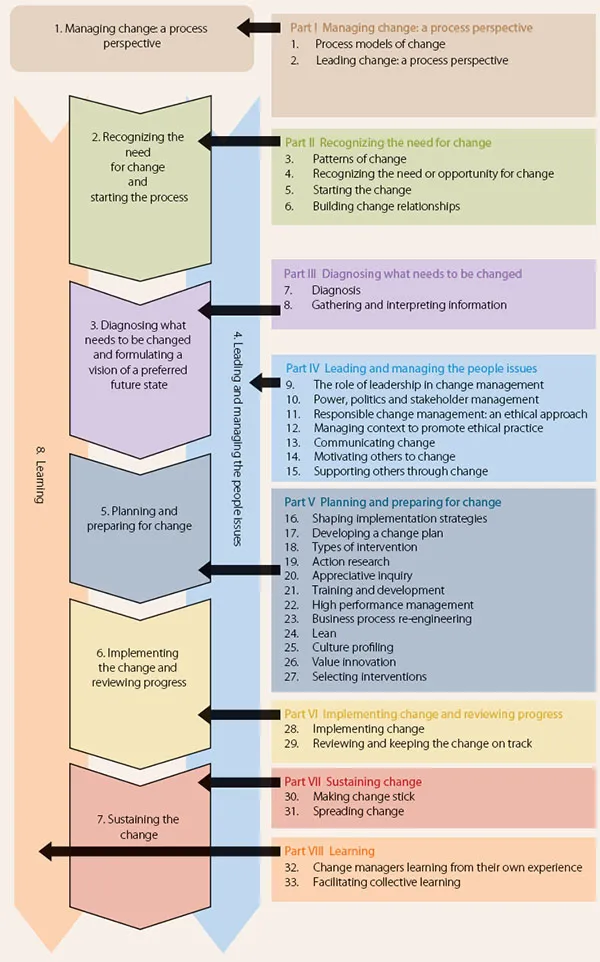

The way in which Chapters 1–33 relate to the generic model is illustrated in Figure I.1.

Figure I.1 How Chapters 1–33 relate to the process model presented in Chapter 2

![]()

Process models of change

Change managers, at all levels, have to be competent at identifying the need for change. They also have to be able to act in ways that will secure change. While those leading change may work hard to deliver improvements, there is a widely accepted view that up to 60 per cent of change programmes fail to achieve targeted outcomes (Beer et al., 1990; Jørgensen et al., 2008). Getting it ‘wrong’ can be costly. It is imperative, therefore, that those responsible for change get it ‘right’, but getting it ‘right’ is not easy. Change agents, be they managers or consultants, are often less effective than they might be because they fail to recognize some of the key dynamics that affect outcomes and therefore do not always act in ways that enable them to exercise sufficient control over what happens.

This chapter examines change from a process perspective, that is, the ‘how’ of change and the way a transformation occurs. After reviewing the similarities and differences between various process theories, attention is focused on reactive and self-reinforcing sequences of events, decisions and actions and how they affect change agents’ ability to achieve intended goals. It is argued that in order to minimize any negative impact from these sequences, those leading change need to be able to step back and observe what is going on, including their own and others’ behaviour, identify critical junctures and subsequent patterns – some of which may be difficult to discern – and explore alternative ways of acting that might deliver superior outcomes.

States and processes

Open systems theory provides a framework for thinking about organizations (and parts of organizations) as a system of interrelated components that are embedded in, and strongly influenced by, a larger system. The key to any system’s prosperity and long-term survival is the quality of the fit (state of alignment) between the internal components of that system, for example the alignment between an organization’s manufacturing technology and the skill set of the workforce, and between this system and the wider system of which it is a part, for example the alignment between the organization’s strategy and the opportunities and threats presented by the external environment. Schneider et al. (2003, p. 125) assert that internal and external alignment promote organizational effectiveness because, when aligned, the various components of a system reinforce rather than disrupt each other, thereby minimizing the loss of system energy (the ‘get-up-and-go’ of an organization) and resources. Effective leaders are those who set a direction for change and influence others to achieve goals that improve internal and external alignment.

Miles and Snow (1984) argue that instead of thinking about alignment as a state (because perfect alignment is rarely achieved), it is more productive to think of it as a process that involves a quest for the best possible fit between the organization and its environment and between the various internal components of the organization. Barnett and Carroll (1995) elaborate the distinction between states and processes. The state (or content) perspective focuses attention on ‘what’ it is that needs to be, is being or has been changed. The process perspective, on the other hand, attends to the ‘how’ of change and focuses on the way a transformation occurs. It draws attention to issues such as the pace of change and the sequence of activities, the way decisions are made and communicated, and the ways in which people respond to the actions of others. Change managers play a key role in this transformation process.

The change process

On the basis of an extensive interdisciplinary review of the literature, Van de Ven and Poole (1995) found over 20 different process theories. Further analysis led them to identify four ideal types – teleological, dialectical, life cycle and evolutionary theories – that provide alternative views of the change process:

•Teleological theories: assume that organizations are purposeful and adaptive, and present change as an unfolding cycle of goal formulation, implementation, evaluation and learning. Learning is important because it can lead to the modification of goals or the actions taken to achieve them.

•Dialectical theories: focus on conflicting goals between different interest groups and explain stability and change in terms of confrontation and the balance of power between the opposing entities.

•Life cycle theories: assume that change is a process that progresses through a necessary sequence of stages that are cumulative, in the sense that each stage contributes a piece to the final outcome, and related – each stage is a necessary precursor for the next.

•Evolutionary theories: posit that change proceeds through a continuous cycle of variation, selection and retention. Variations just happen and are not therefore purposeful, but are then selected on the basis of best fit with available resources and environmental demands. Retention is the perpetuation and maintenance of the organizational forms that arise from these variations via forces of inertia and persistence.

A common feature of all four theories is that they view change as involving a number of events, decisions and actions that are connected in some sort of sequence, but they differ in terms of the degree to which they present change as following certain essential stages and the extent to which the direction of change is constructed or predetermined.

The ordering of stages

Some theories place more emphasis on the order of the stages in the change process than others. For example, life cycle theories are more prescriptive about this than teleological theories. Flamholtz (1995) asserts that ...