![]()

1

. . . . . . . .

The ‘Barbarian’ Middle Ages:

Invasions, Culture, Religion

CHRONOLOGY

410 | The Visigoths sack Rome |

455 | The Vandals sack Rome |

476 | Formal end of the Roman Empire, with overthrowing of Romulus Augustus |

476–93 | Odoacer in Italy |

493–553 | The Goths in Italy (Theodoric) |

535–53 | Byzantine–Gothic wars in Italy |

554–68 | Justinian’s attempt to re-establish imperial authority in Italy |

569–774 | The Lombards in Italy |

590 | Gregory I (the Great) is elected Pope |

751–2 | The Lombards capture Ravenna, the Exarchate and the Pentapolis from Byzantium |

754 | Pope Stephen II asks King Pippin of the Franks for assistance against the Lombards |

754; 756 | Pippin defeats Lombard King Aistulf, who promises to give territories back to the Pope |

758 | Lombard King Desiderius refuses to give territories to the Pope |

773–4 | King Charlemagne of the Franks conquers the kingdom of the Lombards |

800 | Charlemagne is crowned Emperor by Pope Leo III in Rome |

814 | Death of Charlemagne, succeeded by his son, Louis the Pious |

824–30 | Muslims seize strongholds in Sicily |

841 | Muslims occupy Bari |

875–6 | Byzantines reoccupy Bari and other strongholds in southern Italy |

When did the Middle Ages start? The German mathematician Johann Christoph Keller, who lived at the end of the seventeenth century, suggested that they began between 313 (when Constantine’s Edict legalized Christianity) and 326 (when the capital of the Roman Empire moved to Constantinople), though he also considered 395, the date of the division of the Empire by Theodosius. Others proposed different dates, such as the capture of Rome by the Visigoths (410) or the death of Justinian, the emperor of the eastern Roman Empire (565). The Belgian historian Henri Pirenne (author, among many works, of the 1937 classic Mohammed and Charlemagne) argued that only with the Islamic invasions around 650 was it possible to really confirm the end of the Roman tradition, and so he dated the Middle Ages from that time.

By convention, we now regard the start of the Middle Ages as 476, the year when the King of the Eruli and a general of the Roman army, Odoacer, deposed Romulus Augustolus, the last western Roman emperor. That date had no significance for the population of the time, because throughout the fifth century, the western Roman Empire was invaded repeatedly while its organization crumbled. However, in recent decades a new concept of late antiquity has been used, which comprises the third to seventh centuries, therefore eliding a specific turning point or decisive break and emphasizing a slow and imperceptible transition between ancient times and the Middle Ages. The end of the Middle Ages is often considered to coincide with the discovery of America in 1492, a date that was also meaningless to contemporary populations. It is evident that all these dates function only to produce a superficial periodization and offer little help in understanding the slow dialectic of continuity and change provoked by repeated crises and contingencies.

Despite the impossibility of defining precise temporal shifts, some factors did determine the new age and the ways in which Italy took shape as a country from the end of the Roman Empire: the diffusion of Christianity and the organization of the Church; the migration of Germanic peoples with the consequent creation of an ethnically mixed society; the end of the imperial economic system; the beginning of processes which contributed to a separation between East and West, bringing religious unity to crisis point.

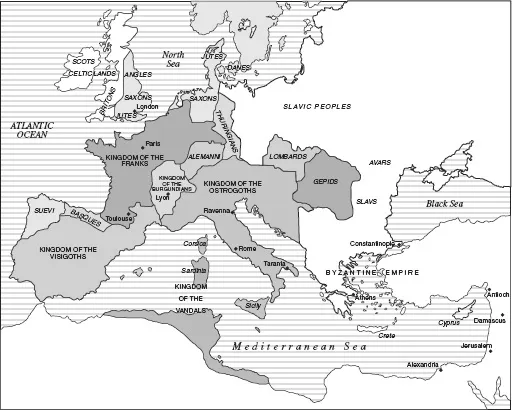

During the imperial age, populations external to Roman civilization were called barbarians. There was a distinction between those who were allowed to reside within the borders of the Empire and obtained the status of federati (allies of Rome), and those who remained outside. The latter included numerous Germanic tribes from the west (Angles, Saxons, Suevi, Burgundians, Alemanni, Franks, Lombards) and tribes from the east (Sciri, Goths, Turcilingi). Under King Alaric, the Visigoths attacked Italy directly and sacked Rome in 410. The Vandals (with the Anglo-Saxons the only sailors among the barbarians), founded a kingdom in 429 in Roman Africa. From there, they conquered the Balearic islands, Sardinia and Corsica, and in 455 sacked Rome for fourteen terrible days: this is the origin of the expression ‘vandalism’, still used today. In 443, the kingdom of the Burgundians was established in Gaul, the Franks occupied the lower Rhine, and the Suevi occupied western Iberia. In 449 the Angles and the Saxons penetrated Britain and integrated with the Celts, creating seven small kingdoms.

Map 1.1 The division of Europe at the beginning of the sixth century

From the time of the barbarian invasions, Italy and the Mediterranean had been major attractions for northern peoples, as Pirenne and Braudel emphasized in their seminal works about the Mediterranean during the Middle Ages. One of their concerns was to integrate history and geography as closely as possible, and they regarded the nature of the land and the climate as fundamental reasons for the invasions. According to Pirenne, the invaders’ dream was ‘to settle down, themselves, in those happy regions where the mildness of the climate and the fertility of the land were matched by the charms and the wealth of civilization’. Most of the chosen countries for the fifth-century invasions were in the Mediterranean; the invaders’ objective was the sea, ‘that sea which for so long a time the Romans had called, with as much affection as pride, mare nostrum’. The invaders saw Italy as the garden of the Mediterranean, an area of abundance and wealth. The Mediterranean had also been the seat of Greco-Roman hegemony and the region of classical culture – an idea later emphasized during the Renaissance, and one that encouraged continual cultural migrations, culminating in the Romantic perception of the Mediterranean shared by Protestant reformers and other northerners in the age of the Grand Tour, from the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries.

The wars that followed the ‘barbarian invasions’, or, as they are also called, the ‘great migrations’, provoked a terrible demographic crisis. As Chris Wickham has argued, Italy was ruined not by barbarian rule but by a succession of wars during the sixth and the seventh centuries. By then, Italy was no longer at the centre of the Western Empire as a whole, and consequently lost important tax revenue. Rome in particular suffered from the loss of African tax payments. The city, which had almost a million inhabitants at the end of the fourth century, was reduced to around 30,000 by the seventh century, even though it was still the second-largest European city after Constantinople. Indeed, the crisis was not specifically Italian: in the third century, Europe had an estimated 65 million inhabitants; but by the middle of the eighth century there were fewer than 30 million.

Populations were decimated by wars and massacres, but also by famine, terrible fires and catastrophic floods. As Bryan Ward-Perkins has recently argued, archaeological evidence shows a dramatic decline in Western standards of living between the fifth and the seventh centuries. The Lombard poet and historian, Paul the Deacon, born around 720 of a Lombard family in Friuli and educated at the grammarian Flavianus’s school in Pavia, wrote: ‘A deep silence reigned over villages and towns. Only dogs remained barking outside the houses, and cattle wandered in the moors without cowherds.’ An Italian prayer known throughout the Middle Ages probably originated from this time: A peste a fame et bello libera nos Domine (‘From plague and hunger and war free us, O Lord’).

The contemporary building of churches demonstrates that, while the Roman heritage survived, new buildings were dramatically smaller. The materials of classical architecture were re-used; capitals, funerary epigraphs and columns were embedded in the structure of new buildings. Artisan workshops were established inside decaying ancient Roman villas and fires were lit on the mosaic floors. As a consequence of the Gothic War, cities were poorer than they had been in Roman times. Archaeological evidence demonstrates that cities experienced a serious crisis, and only slowly began to recover, from the eighth century onwards. Nevertheless, and unlike other parts of the Empire, Italian cities maintained their ancient structure, and that urban continuity is still visible today.

‘MAY YOU LIVE IN HARMONY’: LATIN AND GOTHIC POPULATIONS IN ITALY

When the invaders settled, Italy became characterized by Roman–Barbarian kingdoms, so-called for their dual aspect: Latin-speaking and Germanic populations did not integrate, but coexisted. The double legal system, which continued until the Ostrogothic period, allowed people to be judged respectively by either Roman or Germanic law; in the same way, two different religions were observed, Christian and Arian.

Box 1.1 Arianism

Arianism is the doctrine claiming that Jesus Christ is inferior to the Father. The name came from Arius, a theologian who lived in the third/fourth centuries. He was condemned at the first Council of the Church at Nicea (325), summoned by Emperor Constantine, but, thanks to Bishop Ulfila, who translated the Bible into the Gothic language, Arianism established roots among many of the barbarian tribes.

In the state administration, Roman laws, institutions and organization persisted almost unchanged, but political power and the army were in the hands of the victors, who continued to follow their own traditions. The invaders were a small minority of the population, between 2 per cent and 20 per cent depending on the area. Government duties required a specific culture and training, and since many Germanic military chiefs were illiterate, they had to keep functionaries from the Roman administration. For this reason, many public institutions survived, particularly those related to the administration of justice and taxation.

The Germans imitated the symbols of Roman power, although no barbarian king proclaimed himself emperor until Charlemagne. The invading peoples underwent profound transformations, through a slow fusion between victors and vanquished, becoming the progenitors of the populations of modern Europe. The role that Germanic immigrants had on the creation of Italy has been a contested area for a long time. Recent historiography has moved to what Chris Wickham calls a ‘Romanist direction’, contesting an overemphasis on Germanic influence in the Roman provinces. The elites of the new populations, always small minorities, tended to ‘make the best of what they found’, even though the Roman state, its entire fiscal system and its economic networks had collapsed.

Odoacer was the first barbarian to govern Italy, from 476 to 493. He occupied Dalmatia, developed good relations with the Visigoths and the Vandals (who granted him Sicily as a tribute), and strengthened the northern borders of the empire at the eastern Alps. Although his religion was Arian he created no problems for the existing Church. However, Zeno, emperor of the Eastern Empire (which originated from the division of the Roman empire into a Western and an Eastern part after the death of Theodosius I in 395), who was either nervous of Odoacer’s power or hoped to get rid of the Ostrogoths on his Balkan border, persuaded the Ostrogoths to fight Odoacer. The Ostrogoths were led by Theodoric, who had lived in Constantinople for ten years and had been educated in the values of Roman civilization. They defeated Odoacer, and Zeno granted Theodoric the title of king of the Goths in Italy.

The Ostrogoths were a tiny minority compared with the Roman populations in Italy, but as rulers they only had to live alongside and deal with the Roman elites, not with the majority of the population. Their settlement was not homogeneous, but was concentrated mainly in the centre-north. Under Theodoric, the Roman Church found itself inside a kingdom run by a barbarian of Arian belief, which it considered a heretical version of Christianity. The Arian Church had its own sacred sites and properties. In the urban centres where Goths and Romans cohabited there were Arian churches for the former and Roman churches (much more numerous) for the latter.

Differences between Romans and Goths were also evident in their ways of life. The Romans cut their hair and beards short and wore tunics and, among the upper classes, the toga. Goths had long hair and beards, and wore trousers. The transition from the ancient world to the Middle Ages can be interpreted as a vast process of cultural transformation that resulted from the encounter/clash between classical and barbaric civilizations. This is true also from a dietary point of view: the Greco-Roman civilization had taken shape in a Mediterranean environment, where cereal growing, and grapevine and olive tree propagation had a primary role, alongside some sheep farming, with limited use of uncultivated forests. The dietary culture was therefore based on wheat, oil and wine, supplemented with milk and cheese, though many animal bones have also been found on Roman sites. In mountainous areas, particularly from the ninth century onwards, cereals were replaced by chestnuts, which were also used to make flour. The food consumption of Celtic and Germanic populations north of the Alps was different, marked principally by the lack of olives: the economy was based mainly on forest and pasture, on the exploitation of uncultivated woods through hunting, fishing, the picking of wild fruit and pig breeding. However, cereal growing was central too, mainly used in the production of beer, which replaced wine. Once in Italy, however, Germanic peoples ate what the Italians ate.

The Roman influence became evident, particularly among Germanic elites. A famous treasure found by archaeologists in the Republic of San Marino in 1893, considered to be one of the most important finds from Italy under the Goths, includes the luxurious trousseau of an upper-class woman. The use of the bonnet and the veil, as well as the type of jewellery decoration, is typical of contemporary Mediterranean style, indicating a high degree of acculturation among Gothic communities. As an admirer of Latin civilization, Theodoric co-operated with the Romans, choosing for a number of years Senator Aurelius Cassiodorus, a prestigious intellectual from Calabria, as his adviser and secretary, and placing the philosopher Severinus Boethius, from a powerful Roman family, briefly at the head of his administration. Theodoric proclaimed the Edict of Theodoric which kept Romans and Ostrogoths apart, maintaining Roman law for the former and barbaric law for the latter. He restored fortifications, monuments and aqueducts that had been damaged by the invasions, and created new buildings in Verona, Pavia and Ravenna.

Theodoric regarded himself as the king of both Goths and Romans. To make clear his common kingship over the two peoples, he was buried at his request in a sarcophagus made of porphyry inside a funeral monument built for the occasion just outside Ravenna, near the lighthouse of the port. The tomb’s cupola is 34 metres in circumference and made from a single block of Istrian stone. At the church of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, a mosaic portrays Theodoric as a Byzantine emperor (though his name was later erased and replaced by that of Justinian, emperor of the Eastern Empire).

Theodoric’s attempts to reconcile Latins and Goths failed, because of Justinian’s intervention: the new Eastern emperor proclaimed an edict of persecution against the Arians in 524, which was extended to Italy, demonstrating that he still considered Italy to be his possession. The period of war between the Goths and the Eastern Empire from 535 to 553 was the worst time for the population of Italy since the first invasions in the fifth century. The Byzantine general, Belisarius, at the head of Justinian’s army, attacked from the south, first conquering Sicily and proceeding without hind...