![]()

Map 1England and Wales, Autumn 1643 (adapted from Martyn Bennett, The English Civil War, London: Longman, 1995, p. 48).

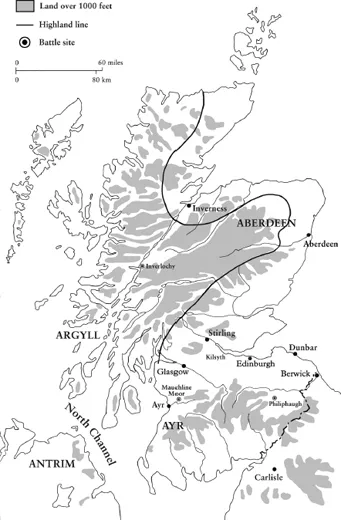

Map 2Scotland (adapted from David L. Smith, A History of the Modern British Isles, 1603–1707, Oxford: Blackwell, 1998, p. 13).

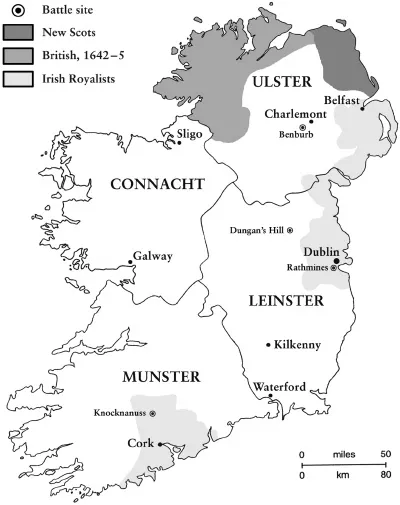

Map 3Ireland, Summer 1643 (adapted from Martyn Bennett, The Civil Wars in Britain and Ireland, 1638–1651 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997).

![]()

Chapter 1:Society, War, and Allegiance in the Three Kingdoms, 1637–42

The State of the Stuart Nations

England

Looking back on the England he had known in the 1630s, the statesman and historian Sir Edward Hyde observed a familiar English trait: ‘the truth is, there was … little curiosity either in the Court or the country to know any thing of Scotland, or what was done there … nor had that kingdom a place or mention in one page of any gazette, so little the world heard or thought of that people’.1 Since 1603, when the Scottish king, James Stuart, had succeeded Elizabeth Tudor, England and Ireland had been joined with Scotland through the person of the monarch (and little else). James’s son Charles had inherited this ‘union of crowns’ in 1625, and though he had been born in Scotland, and even spoke with a Scottish accent, the English thought of him first and foremost as king of England. If he chose to rule other kingdoms ‘in his spare time’ it was no concern of theirs. Little wonder then that when rebellions in Scotland and Ireland precipitated civil war in their own country, the English were generally at a loss as to how this calamity had come about.

The English blind-spot when it came to the king’s ‘other’ kingdoms arose partly from chauvinism – a belief in the superiority of England, her people and institutions, over other countries. Yet it also reflected a fundamental truth about the relative power and importance of the constituent parts of the Stuart dynastic agglomeration. England was the wealthiest and most powerful of Charles’s domains. Its population on the eve of civil war numbered close on five million, which was almost twice that of Scotland, Wales, and Ireland put together. Although the vast majority of the English lived in rural settlements, reflecting the predominantly agrarian nature of the economy, England was a more urbanised society than most of its neighbours. Bristol, Newcastle, York, and several other provincial capitals could boast populations of over 10,000; while London, with its 400,000 or so inhabitants, was the largest metropolis in western Europe. A large slice of the kingdom’s rapidly expanding overseas trade passed through the City, which also made it one of Europe’s principal money markets.

Fittingly for a city of such disproportionate size and wealth, London was the centre of what, by contemporary standards, was a highly centralised state. All government, civil as well as ecclesiastical, derived from the person and authority of the king; and access to this font of power and patronage was through the royal court at the Palace of Whitehall, in London. It was here that Charles and his queen, Henrietta Maria (sister of Louis XIII of France), normally resided, and that royal government was conducted. The king, aided by his privy council (which comprised the principal ministers of state) and other executive bodies, exercised a wide range of prerogative – that is, discretionary – powers, including the appointment of bishops, judges, and county officials such as JPs.

The crown’s most prized prerogatives were the right to call and dissolve Parliaments, and to veto legislation passed by the two Houses – the so-called negative voice. Parliament, pre-1640, had several functions: it represented the people’s grievances to the monarch; cooperated with the crown in passing laws (statutes); and voted the king taxes (subsidies). Parliament’s role as the king’s great council, which he could summon and dissolve at will, and the fact that it neither possessed nor sought executive powers, meant that it had no direct involvement in governing the country. Nevertheless, the Westminster Parliament was far more influential than its Scottish and Irish counterparts. The authority of king-in-Parliament, as represented by statute law, carried the greatest legislative force in the land. Indeed, there was a strong body of opinion that statute and the mass of accumulated legal precedents it elaborated – known collectively as the common law – defined and limited the royal prerogative. English identity itself was interwoven with an acute sense of England’s constitutional and legal exceptionalism; an unshakeable belief in the antiquity, superiority, and sovereignty of her laws.

Despite the restricted nature of the electoral franchise – women, servants, and the indigent poor being denied the vote – Parliament had become identified in an almost mystical sense with the entire nation. At a time when the power of princes was thought to be growing at the expense of their subjects’ rights, Parliament was regarded as the guardian of English ‘liberties’ such as habeas corpus and the principle of no taxation without consent. The preservation of these liberties, moreover, had become indelibly associated with the defence of English Protestantism and national autonomy against ‘popery’ (international Catholicism), which was synonymous in popular perception with tyranny over body and soul. Thus Parliament was a focus for patriotic feeling and zeal for ‘the true Protestant religion’. Above all, regular Parliaments were thought to act as lightning conductors for domestic discontent – an important role in a realm where, in the absence of a trained police force, large salaried bureaucracy, or standing army, government depended upon the consent of the governed and the voluntary cooperation of local office-holders.

The English reverence for Parliaments was the product of a politically well-informed and engaged public – a phenomenon related to deeper trends such as increasing social differentiation and rising literacy levels. Improvements in agriculture and trade in the century before 1640 had created an industrious ‘middling sort’ that was keen to join the fight against popery and disorder at all levels, from common drunkenness to the presence of ‘evil counsellors’ at court. Some of the kingdom’s 15,000 or so gentry felt threatened by the increasing assertiveness of the lower orders, and looked for ways to promote hierarchy and deference. Others, however, sought to harness the concerns of the middling sort to further local campaigns for moral reform or to pressure the crown for an aggressively anti-Catholic foreign policy. Even great aristocrats were not above courting popular support. The Earl of Warwick, for example, could rally large numbers on his home soil of Essex as the champion of liberties and true religion. He and his circle believed that civil liberties must be earned through strenuous public service – a notion that chimed perfectly with the urge towards active citizenship among the middling sort. This state of political symbiosis between commoners and elites illustrates the dynamism yet stability of English society. The majority of peers, however, sustained their political pre-eminence by more traditional means. They dominated high office at court and in their counties, and many derived additional influence as great landowners. Noblemen such as the earls of Newcastle and Northumberland were regional magnates, whose estates dwarfed those of most gentry.

The very vibrancy of English society was a source of political tension. Rising prices, together with the demands of war against Spain and France in the 1620s, obliged the crown to seek additional funds in the form of parliamentary subsidies. Yet, Parliaments, mindful of popular concerns over popish influences at court and perceived mismanagement of crown revenues, proved reluctant to vote for subsidies until the people’s grievances had been redressed (a formula that prevented the crown from tapping all but a fraction of the nation’s wealth). Some of this reluctance, moreover, was couched in the language of the subjects’ liberties and common law limitations upon the royal prerogative. Insecure in his person and authority, Charles did not react well to any sign of non-compliance from his subjects. Seen through his eyes, the unsettling changes that were occurring within English society became a populist conspiracy against monarchy and the social order. His response, as Richard Cust and Ann Hughes have shown, was to ‘ “close down” the political system; to avoid Parliament if possible, to emphasise hierarchy, order, and honour, and to insist on absolute obedience’.2

Charles’s over-compensating desire for order in the face of ‘popularity’ coloured all aspects of his rule. It encouraged him to adopt ‘new counsels’ that pronounced him answerable to God alone, and thus justified in resorting to prerogative taxation. It strengthened his resolve to do without Parliaments from 1629, and to deny their more fervent advocates a foothold at court. Most importantly perhaps, it shaped his religious views. Charles advanced clerics such as William Laud (whom he made archbishop of Canterbury) who shared his passion for ceremony and order in church worship, as well as his exalted notions concerning the royal supremacy in religion. Not since Edward the Confessor had England had such a pious monarch, nor one so dedicated to church reform. The problem was that in religion, as in much else, Charles stood outside the mainstream of English opinion. A significant section of the political nation believed that the ultimate arbiter in church matters should be king-in-Parliament rather than royal prerogative. The gentry resented the Caroline trend towards greater clerical involvement in temporal affairs. And many people were wedded to the familiar liturgy of the Book of Common Prayer, and could muster little enthusiasm for Laudian innovations. Moreover, to the ‘hotter sort of Protestants’, and particularly to the Puritans – those members of the Church of England eager to cleanse it of Catholic vestiges – Laudian ceremonies smacked of outright popery. Although relatively few in number, and subject to increasing state harassment from the late 1620s, the Puritans were an influential grouping. They were represented at almost every social level, and by promoting a preaching ministry and godly magistracy they hoped to realise their vision of the English as an elect nation under God. Laudianism they regarded as a stalking-horse for the restoration of papal authority in England, and rather than suffer the attentions of the ‘Romish whore’ some of them emigrated to the American colonies.

Wales

Wales had been joined with England formally in the 1530s and 1540s, when English law and administration had been extended throughout the principality and the Welsh were granted the right to send MPs to Westminster. The majority of Wales’s 400,000 or so inhabitants were monoglot Welsh-speaking, although there were enclaves of English-speakers in south Pembrokeshire and the Gower. Because of the language barrier, and the country’s relative poverty and difficult terrain, Wales had not been evangelised by Protestant reformers to anything like the degree that parts of lowland England had. But the Welsh were none the less a Protestant people. Care had been taken in Tudor times to translate the liturgy of the Church of England into the native tongue, and the majority of Welsh were sincerely attached to Prayer Book worship and the communal pastimes that accompanied it.

In a fresh and stimulating look at the Welsh and their Celtic cousins the Cornish during the Civil War, Mark Stoyle has attributed to both peoples a strong sense of ethnic and national identity, and depicted their Royalist allegiance as partly an expression of ‘national independence’.3 Racially and culturally, the native Welsh (and, for their part, the Cornish) certainly formed a distinct body of people within the Stuart realm. And given the paucity of peculiarly Welsh institutions, religious creeds, or legal codes, it would seem that the only solid basis for Welsh ‘nationalism’ was indeed a sense of ethnic separateness. Unfortunately, we know too little about the native Welsh in this period to say whether they defined themselves primarily by blood, language, and other ethnic traits. Their gentry leaders, of whom they rarely acted independently, certainly did not. In terms of government, politics, and religion at least, the Welsh were entirely ‘jointed in’ to the English state, making it very difficult – as Peter Gaunt and John Morrill have argued – to identify a dimension to the Civil War in Wales that is not mirrored in parts of England.4

Stoyle’s focus on the ‘dark forces of ethnic hatred’ in the wars of the three kingdoms – or as he prefers, ‘a war of five peoples’: English, Scots, Irish, Welsh, and Cornish – is least convincing when applied to the English. The English people’s ethnic identity was not central to their sense of Englishness, which they defined primarily in regnal, juridical, and confessional terms. If they thought of the Welsh, Irish, and Scots at all, it was not as irredeemable racial ‘others’ – as the Spanish regarded the Jews and Moors, for example – but as benighted outlanders in need of the civilising influence of English laws and customs.

Ireland

Tudor rhetoric that the kingdom of Ireland was ‘united and knit to the Imperial Crown of the realm of England’ had been essentially that – rhetoric. Not until the very last year of Tudor rule, when Elizabeth’s forces defeated the Ulster Gaelic leaders in the Nine Years War (1594–1603), did the crown succeed in bringing all of Ireland under its control. Before then, the full exercise of royal authority had been limited mainly to the Pale – a narrow strip of land around Dublin in the eastern province of Leinster. Much of the territory in the three other provinces – Munster, Ulster, and Connacht – had been under the sway of powerful overlords, some of whom paid little heed to the Dublin administration.

In the four decades of peace that followed the Elizabethan conquest, Ireland’s population grew to between 1.4 and 2 million. The Irish economy too was expanding during the early seventeenth century, although from a very low base. Industry was limited to rudimentary woollen manufacture, small-scale urban artisanry, and a few iron-smelting ventures in Leinster and Munster. Large parts of the country, particularly in Ulster and Connacht, remained covered in forest and bog, and the majority of the people lived directly off the land in conditions that to English eyes appeared primitive. Overseas trade was dominated by the export of cattle, wool, and hides to England, and was concentrated in the ports of the eastern seaboard. Dublin, which enjoyed about a third of this export trade, was easily Ireland’s largest town, with a population of about 20,000 by the 1630s.

The growth of the Irish economy was underpinned by the gradual extension of the common law system throughout Ireland. English-style property rights and tenurial relations were already spreading beyond the Pale by the late sixteenth century, as Gaelic chiefs began to take out legal title for their land from the crown, and to impose leases and levy rents o...