![]()

Part

1 | Introducing Working with Children and Families |

![]()

| Working Together with Children and Families | 1 |

Robert Adams

LEARNING OUTCOMES

By the end of this chapter, you should be able to:

understand the structure of children’s services across the UK

understand key aspects of policy and law for children and families, including Every Child Matters and the Children Act 2004

identify key themes of working with children and families

This chapter provides a critical context for the study of children and the practice of working with them, whether in education or social services. It offers a general introduction to services for children and their families, as well as the main policies and legal contexts. The practice of work with children, their parents, carers and families is shaped by the major policy and legal changes of the early 21st century, and particularly by the services and provisions put in place by past and present governments.

Services for children and their families

The policy and legislative basis for children’s services in the 21st century in England and Wales is expressed in the Children Act 1989 and the Children Act 2004, the latter stimulated by the inquiry report into the death of Victoria Climbié (Laming, 2003), which led to the Green Paper Every Child Matters (DfES, 2003a). In England, the Children Act 2004 led to:

the creation of children’s trusts, bodies responsible for setting the strategic policy for services and delivering these services through a partnership board of participating agencies, organizations and groups

new children’s services departments being formed from the merger of local authority education and social services departments.

The aim of this was to bring about more integrated, that is, ‘joined-up’, services than formerly.

In Wales, similar functions are still carried out by education and social services. In Scotland, most of the social work services for children and families are commissioned directly by the 32 local authority social work departments, whereas education services, including schooling, are provided separately by local authorities. In Northern Ireland, the Department for Education is responsible for children’s education services and the Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) for social services.

The policy on children’s trusts is changing as this book is being written. The coalition government (2010 onwards) announced in July 2010 that a forth-coming Education Bill would downgrade the importance of children’s trusts, remove the obligation on local authorities to set up a children’s trust board and withdraw statutory guidance on the Children and Young People’s Plan (the blueprint for children’s services).

A symbol of the increasing importance to policy makers and practitioners of children’s rights in the UK is the creation of children’s commissioners, responsible for promoting awareness of children’s views, interests and rights. The first of these children’s commissioners was appointed in Wales in 2001, the second in Scotland in 2002 and the third in Northern Ireland in 2003. In England, the first children’s commissioner was not appointed until 2004, under the Children Act 2004.

Let us take a closer snapshot of the way children’s services are organized in the UK. A complex array of services for children and families is maintained by national and local government in the four countries of the UK. Since the general election of May 2010, when the coalition government replaced the Labour government (1997–2010), responsibility for children’s services in England rests with the Department of Education.

Services in England

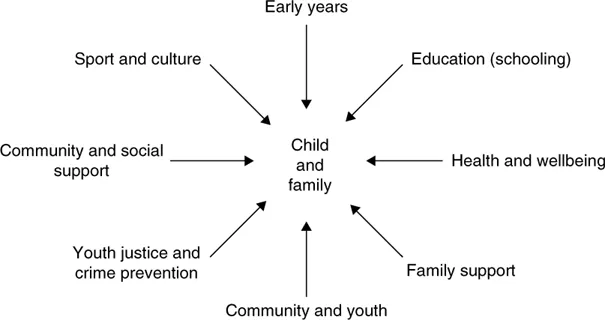

Since 2009, the director of children’s services, who also directs children’s social services, has taken over from the former local education authorities the responsibility for administering local education in the state sector. Figure 1.1 illustrates the different functions of children’s services in a typical local authority. These are carried out by trusts, agencies, departments and groups in health, education, social services, youth justice, housing, community and environment and providers in the third sector, that is, private, voluntary and independent bodies and groups. Details of the typical practitioners employed in these different sectors are shown in Table 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Functions of children’s services in an English local authority

Table 1.1 Examples of practitioners in different sectors

| Sector | Examples |

| Health | Nurses, midwives, health visitors, general practitioners (GPs), paediatricians, dentists, ophthalmologists, clinical psychologists, mental health workers, dieticians, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, speech therapists |

| Education | Teachers, educational psychologists, education welfare officers, learning mentors, support workers |

| Social services | Social workers, care workers, childminders, foster carers, early years staff, home carers, substance abuse workers |

| Youth justice | Youth offending team staff, probation officers, police officers, community support officers, domestic violence staff, juvenile home staff |

| Housing, community and environment | Housing officers, benefits staff, community workers, workers in different faiths, leisure and sporting workers |

| Third sector | Care workers, support workers, volunteers |

The Care Standards Act 2000 established the framework for the registration of practitioners in social services. The Commission for Social Care Inspection established under the 2003 Health and Social Care (Community Health and Standards) Act and the Commission for Healthcare Audit and Inspection set up in 2004 (later known as the Healthcare Commission) were replaced in 2009 by the Care Quality Commission (CQC). The CQC is responsible for registering, inspecting and reporting on adult social care services in England. The Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted), which was set up in 1992, inspects children’s services, under the Children Act 2004 (Box 1.1), which amended some of the arrangements made under the Care Standards Act 2000 (Box 1.2).

Box 1.1 Children Act 2004

• Put in place a single children’s services department in each local authority

• Ensured that by 2006 each local authority had a Children and Young People’s Plan

• Generated mechanisms to create children’s trusts to allocate funding to children’s services by 2008

Box 1.2 Care Standards Act 2000

• Created mechanisms for regulating private and voluntary healthcare in England

• Set up systems for regulating and inspecting healthcare and social care in Wales

• Established independent councils and registers for practitioners in social care, including social work

Services in Wales

In Wales, the DHSS is responsible for the children’s commissioners, the Healthcare Inspectorate Wales and the Care and Social Services Inspectorate Wales, which regulates adult and children’s services and works directly to the National Assembly of Wales, independent from the Welsh Assembly Government. Through these mechanisms, the governance of Wales in less independent from England than Scotland, but more independent than Northern Ireland. In social services in general and children’s and families’ services in particular, the direction of policy in Wales puts a greater emphasis than in England on promoting the rights of children and young people.

Services in Northern Ireland

In Northern Ireland, health and social care are provided as integrated services through the central Department for Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) and the Health and Social Care Board. There are five Education and Library Boards responsible for education provision within the local council areas. There are six Health and Social Care Trusts, five of which provide integrated health and social care services across Northern Ireland, the sixth being the Northern Ireland Ambulance Service. The Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority regulates health and social care services, including social services for children and adults, inspected by the Office of Social Services in the DHSSPS.

Services in Scotland

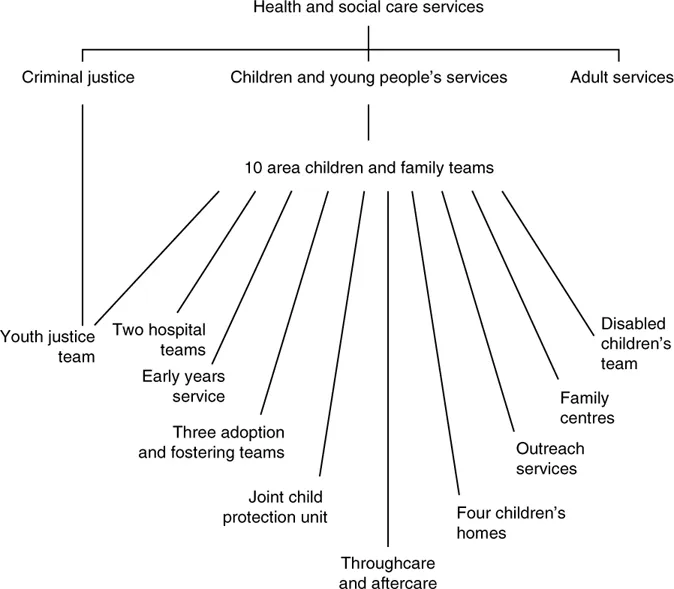

In Scotland, the councils in each council area retain responsibility for local government services; for instance, there are generic departments for adult and children’s services. So health and social care services include criminal justice as well as adult services and services for children and young people. Figure 1.2 provides an example of how provision is organized in a Scottish city setting.

In Scotland, the Care Commission regulates standards of social care services under the Regulation of Care (Scotland) Act 2001, through the Social Work Inspection Agency, which is responsible for regulating and inspecting social care in general. On 1 April 2011, the work of the Social Work Inspection Agency passed to a new body, Social Care and Social Work Improvement Scotland. The HM Inspectorate of Education (Scotland) participates in joint inspections of children’s services.

Figure 1.2 Example of a Scottish city council’s health and care service

Point for reflection

In your opinion, to what extent should the government be involved with the upbringing of a child in modern society?

Policy and legal developments leading to 21st-century children’s services

In 2000, the Framework for the Assessment of Children in Need and their Families (DH/DfEE/Home Office, 2000) made it clear that services and work with children must take place in the context of work with the family. This was follo...