eBook - ePub

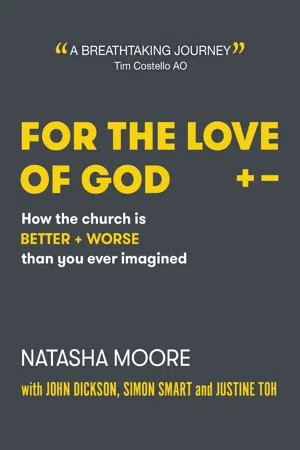

For the Love of God

How the church is better and worse than you ever imagined

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

For the Love of God

How the church is better and worse than you ever imagined

About this book

Christianity, depending on who you ask, is either a scourge on our society, narrow, delusive, and inevitably producing hatred and violence; or the foundation of some of the best elements of our culture and a continued source of hope, comfort to those in need, and moral inspiration. Are we talking about the same people here? Are we looking at the same history?

Crusades, witch hunts, slavery, colonialism, child abuse … the history of the church offers plenty of ammunition to its critics. And on the other hand: charity, human rights, abolition, non-violent resistance, literacy and education.

In For the Love of God, Natasha Moore confronts the worst of what Christians have done, and also traces the origins of some of the things we like best about our culture back to the influence of Jesus.

Covering episodes from the Spanish Inquisition to Martin Luther King Jr, Florence Nightingale to the "humility revolution", this book offers an accessible but wide-ranging introduction to the good, the bad, the ugly – and the unexpected – when it comes to the impact Christianity has had on the world we live in.

Crusades, witch hunts, slavery, colonialism, child abuse … the history of the church offers plenty of ammunition to its critics. And on the other hand: charity, human rights, abolition, non-violent resistance, literacy and education.

In For the Love of God, Natasha Moore confronts the worst of what Christians have done, and also traces the origins of some of the things we like best about our culture back to the influence of Jesus.

Covering episodes from the Spanish Inquisition to Martin Luther King Jr, Florence Nightingale to the "humility revolution", this book offers an accessible but wide-ranging introduction to the good, the bad, the ugly – and the unexpected – when it comes to the impact Christianity has had on the world we live in.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access For the Love of God by Natasha Moore,John Dickson,Simon Smart,Justine Toh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Worst of the Worst

It is the early spring of 1210, and a line of mutilated men – eyes gouged out, noses cropped, lips cut off – snakes its way across the French countryside. The pope’s army has sacked their hometown of Bram, and dispatched this gruesome procession to a neighbouring town as a warning of what is to come.

It is 1300, and the church has declared a Jubilee. Pilgrims, many of them poor but devout, flock to Rome. They show their piety by surrendering their gold: at one basilica, priests have to use rakes to collect the mountain of coins heaped around the shrine each day.

It is 1495, and the Spanish Inquisition is in full swing. In cities like Seville and Toledo, many live in continual fear of being hauled before the tribunal. Torture is routine. Neither age nor sex gives the zealous inquisitor pause; both children and women in their nineties are subject to the rack, the pulley, or water torture – though it is reported that pregnant women are sometimes allowed to sit while being tortured.

It is 1850, and millions of Africans and their descendants have been enslaved in the “land of the free” over the last 230 years. Slave-owners deploy the Bible to shore up their position; as one preacher declares in disgust, “There is no power out of the church that could sustain slavery an hour, if it were not sustained in it”.

It is 1982, and in Boston Margaret Gallant is writing to her cardinal, in anger and sorrow. A priest who has molested a total of seven boys in her extended family has been returned to his parish and continues to have access to children, whose parents know nothing of his crimes.

How can this be?

How can people call themselves followers of a man who came in poverty and humility, proclaiming peace and justice, offering compassion and forgiveness, urging self-denial and love of neighbour and enemy alike, who gave up his life for others, and then commit acts like these?

What is Christian faith worth, if it doesn’t restrain such behaviour, and in some cases even seems to furnish justifications for it – not to mention a warm glow of self-righteousness?

Would we be better off, after all, without religion?

CHAPTER 1

CRUSADES

NOW THAT OUR MEN HAD POSSESSION of the walls and towers, we saw some wonderful sights … Piles of heads, hands, and feet were to be seen in the streets of the city. One had to pick one’s way over the bodies of men and horses. But these were small matters compared to what happened at the Temple of Solomon. You would not believe it if I told you. Suffice to say that in the Temple and porch of Solomon men rode in blood up to their knees and bridle reins. Indeed, it was a just and splendid judgment of God that this place should be filled with the blood of the unbelievers …

Now that the city was taken, it was well worth all our labours and hardships to see the devotion of the pilgrims at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. How they rejoiced and sang a new song to the Lord! Their hearts offered such prayers of praise to God, victorious and triumphant, as cannot be told in words … This day, I say, will be famous in all future ages, for it turned our labours and sorrows into joy and exultation. This day, I say, marks the justification of all Christianity, the humiliation of paganism, and the renewal of our faith. “This is the day which the Lord hath made, let us rejoice and be glad in it,” for on this day the Lord revealed Himself to His people and blessed them.

When around 10,000 European Crusaders broke through the walls of Jerusalem in July 1099, they proceeded to carry out a massacre of biblical proportions. The Muslim inhabitants of the city sought refuge in the Al-Aqsa Mosque, Islam’s third-holiest site, barricading themselves in. But the soldiers broke through and slaughtered thousands of men, women, and children, throwing some off the high walls, putting the rest to the sword.

As recounted by the Provençale chronicler Raymond of Aguilers, when the slaughter was over, the Crusaders marched to the nearby Church of the Holy Sepulchre – traditionally revered as the site of Calvary, where Jesus had submitted to a shameful and unjust death a millennium earlier – and held a thanksgiving service.1

These supposed “knights of Christ” believed they were not only doing the will of God, but earning his forgiveness for their (many!) sins. This was something new and surprising: salvation for taking up the sword. Religious wars have been common across human history, but the idea that fighting might be spiritually meritorious – like giving to the poor, or going on a pilgrimage – was something of an innovation of this, the First Crusade.

It all began with a church council held in Clermont, France, in the middle of 1095. On the final day of the council, Pope Urban II preached a sermon that was to change the course of history. He had received a plea for help from the Christian emperor of Byzantium (modern-day Istanbul), who was facing attacks from Turkish forces. Urban urged the crowds to head East to rescue their fellow Christians; to channel their violence for “good” rather than fighting each other at home. He issued a decree: “Whoever for devotion alone, not to gain honour or money, goes to Jerusalem to liberate the church of God can substitute this journey for all penance.”

The appeal struck a chord across Europe; tens of thousands signed on for the arduous journey East, heeding the call of fiery preachers like Peter the Hermit, who travelled around whipping up support for the campaign. Everywhere he went, enormous crowds gathered; prostitutes came forward and vowed to become nuns; he brought props with him, actual crosses that he laid on those who committed to the Crusade in response to his preaching. This was a strange inversion of Jesus’ command to “take up your cross”. In place of a call to self-denial – to willingly embrace suffering, rejection, and weakness for his sake – it was a call to arms and to glory.

How did these followers of a crucified leader, who eschewed violence and forbade his disciples from taking up the sword to defend him or his “cause”, end up here, in the precinct of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, butchering perhaps thousands of civilians in his name?

The first Christians took to heart what remain, two millennia on, some of the most startling of Jesus’ teachings. “You have heard that it was said, ‘Eye for eye, and tooth for tooth’”, he tells the crowds in what would become known as the Sermon on the Mount. Taking up key tenets of Jewish law and tradition, he recasts and radicalises them:

But I tell you, do not resist an evil person. If anyone slaps you on the right cheek, turn to them the other cheek also. And if anyone wants to sue you and take your shirt, hand over your coat as well. If anyone forces you to go one mile, go with them two miles. Give to the one who asks you, and do not turn away from the one who wants to borrow from you.

You have heard that it was said, “Love your neighbour and hate your enemy.” But I tell you, love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you, that you may be children of your Father in heaven. He causes his sun to rise on the evil and the good, and sends rain on the righteous and the unrighteous. If you love those who love you, what reward will you get? Are not even the tax collectors doing that? And if you greet only your own people, what are you doing more than others? Do not even pagans do that? Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect. (Matthew 5:38–48)2

To be like God, Jesus insists, is not to return insult with insult, hostility with hostility, but to respond to being wronged with blessing.

It wouldn’t be long before the resolve of the early Christians to forgo vengeance and choose to love their enemies instead was tested. The first state-sponsored persecution of the church began in 64 CE, when the Emperor Nero found it convenient to blame the new movement for a devastating fire that swept Rome for six days, destroying large sections of the city. According to the Roman historian Tacitus, Christians were seized and imprisoned, thrown to wild dogs to be torn apart, fastened to crosses and burned to serve as gruesome lamps in Nero’s gardens.

Some decades later, a letter that one church leader (himself soon to be martyred in Rome) wrote to Christians in Ephesus reaffirms how Jesus’ followers ought to react to hostility and persecution. Ignatius, Bishop of Antioch, urged the Ephesian church:

In response to their anger, be gentle; in response to their boasts, be humble; in response to their slander, offer prayers … in response to their cruelty, be civilised; do not be eager to imitate them. Let us show by our gracious forbearance that we are their brothers and sisters, and let us be eager to be imitators of the Lord …3

“The early Christians for the first three centuries assumed that what Christ’s sacrifice meant was that you would prefer to go to your death rather than shed blood”, explains Catholic historian William Cavanaugh. This church was full of martyrs, not soldiers; Christians who did join the Roman military were usually criticised by their fellow believers. “It’s not until the Roman Emperor himself becomes a Christian in the fourth century”, continues Cavanaugh, “that Christians begin to develop justifications for the shedding of blood.”4

The emperor Cavanaugh’s referring to is Constantine, who in 312 CE secured the throne with a decisive victory over his rival Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge. Some sources suggest that Constantine had a dream where he was commanded to fight under the banner of the Christian cross; others that he beheld a vision of the cross in the sky, accompanied by the words in hoc signo vinces, “in this sign conquer”. Either way, the new emperor attributed his success to the Christian god, and converted.

This moment marked a significant shift for the early church. Though it isn’t true that Constantine made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, or forced anyone to adopt it, his patronage put an end to centuries of periodic persecution and brought public funding, recognition, and a new measure of power to the church. This proved a mixed blessing, and historians continue to debate its implications. Many interpret this as the moment Christianity lost its way and was irrevocably corrupted by power; others see it as a natural and even inevitable next step in the growth of the church and its influence – as more people across the known world and up and down the social scale became Christians, their impact on not only the social and cultural but also political life of the empire would grow.

Teresa Morgan, Professor of Graeco-Roman History at Oxford, weighs both sides:

Undoubtedly Christianity changed. It became more establishment. It became more interested in money. It became more interested in protecting itself and its own prestige because of being allied with imperial power. On the other hand, it acquired opportunities to do what it saw as good … it’s always a very two-edged thing, acquiring political power – for any religious tradition probably, including early Christianity.

As the church became increasingly implicated in affairs of state, Christian thinkers and office-holders had to figure out how to approach the complex realities of public justice and warfare. Some of their efforts, such as the development of “just war theory”, aimed to make war a last resort and to mitigate its worst effects. This concept of just war, first developed by the fifth-century bishop and philosopher Augustine, conceded that violence may sometimes be necessary, and in so doing may have opened the door to later religious justifications for heading into battle.5

Public intellectual and former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams describes the progression:

Augustine is saying, “Look, things are falling apart. The world is pretty difficult. There are circumstances where you have got to do what isn’t ideal. If, in order to fight off marauding barbarian tribes from northern Europe, you need to take to battle, well, all right, I suppose. I mean it’s not a good thing, but the alternative is probably worse. And if you are going to do it and still remain some kind of a Christian, then for goodness’ sake keep in mind the following moral principles. Nothing will make some behaviour good.” So it’s a very grudging concession. It’s certainly very different from the Crusader marching off to recover Jerusalem, shouting “God wills it”.

If Christians began to change the way warfare was conducted from the fourth century onwards, that influence was a two-way street. In particular, as the Germanic successor states to the Roman Empire were Christianised, the church in turn became imbued with the warrior ethic of those tribes. Early medieval texts depict Christ as a kn...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: Does Religion Poison Everything?

- Part I: Worst of the Worst

- Part II: Best of the Best

- Part III: It’s Complicated

- Part IV: Surprises

- Part V: Big Ideas

- Part VI. To Change the World

- Conclusion: So What?

- Appendices