![]()

1

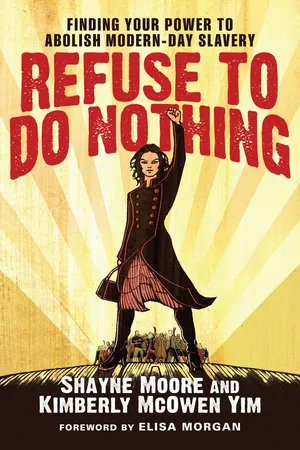

Mama, Slavery Ended with Abraham Lincoln

Kimberly McOwen Yim

When the true history of the antislavery cause shall be written, women will occupy a large space in its pages; for the cause of the slave has been peculiarly woman’s cause.

Frederick Douglass

“Scotty, I asked you to find your backpack!” I holler as I shove my ponytail in a baseball cap. “Hurry! Get in the car! We’re going to be late!”

Despite my best efforts, Mondays are always chaotic. When my husband takes the kids to school, they’re somehow always early. But with me—we just barely get there on time.

As I climb in the car I catch a glimpse of the kitchen counter through the screen door. “Malia! Your lunch. It’s on the counter.” I gesture dramatically. “Go get it!”

The sun is shining brightly as we drive down the long hill leading to the coast and the kids’ school. I have never tired of looking at the Pacific Ocean; I love to see how the weather changes its color each day.

“Okay, Scotty. Do you remember your lunch number? Remember—it’s pizza day. Make sure to raise your hand so Mrs. Becerra knows to count you in the list for kids who are buying lunch today.”

“I don’t like to buy lunch anymore,” Malia jibes.

“You did when you were in kindergarten.” I pull down the rearview mirror to give her the stinkeye. “Scotty, pizza day is always fun.”

My phone rings. “Hey, Julie, how are you? . . . Yeah . . . Uh-huh . . . No, I haven’t touched base with her yet. I will . . . Okay, yes. I’m planning on it. I’ll bring the materials tonight. Lisa is joining us tonight as well. I’ll call you later. I gotta go. I’m at the kids’ school.”

I pull into a coveted space along the park across the street from the school. The kids tumble out of the car, and we walk the rest of the way. “Remember, I’m not picking you up from school this afternoon. Grandma is, okay?”

Malia struggles with her roller backpack, trying to pull it across the grass. “Why?”

“Remember, I told you. I’m going to a conference. Grandma knows where to meet you.”

Malia persisted, “What kind of conference, Mom?”

In a few hours I’ll be headed to Carlsbad, California, for the first Global Forum on Human Trafficking. Sponsored by the Not For Sale Campaign and Manpower, Inc., it will be the first conference I attend on the subject of human trafficking. I’m hoping to learn more about this issue that recently broke my heart.

Scotty and I push our way through the small crowd outside his classroom to the sign-in table. “Scotty, here. Sign your name.” I say to Malia over my shoulder, “It’s a conference on slavery.”

Kind of a big thing to drop on a third-grader moments before school starts.

Malia looks at me thoughtfully. Then, with an air of first-born authority, she says, “Mama, slavery ended with Abraham Lincoln.”

The five-minute bell rings, saving me from having to craft a response.

“We’ll talk about it later. There’s your bell. Run to class. Love you.

Despite our age difference and different levels of formal education, Malia and I were not that far apart in our understanding of what’s going on in our world. Until recently I too believed slavery ended with the Emancipation Proclamation and the end of the trans-Atlantic African slave trade. I only recently learned that there are millions of people enslaved in our world today.

When I did discover the extent of modern-day slavery, I became sick, sad and furious. The lioness within me awoke hungry for justice. I began to see myself aligned with passionate abolitionist women from two hundred years ago. Women like Lucretia Mott and the Grimke sisters, who did not stand on the sidelines but actively participated and provided much leadership in the anti-slavery movement of the mid-1800s. They organized female abolitionist societies because during that time women and men were not allowed to participate in the same groups—even anti-slavery groups. These women organized boycotts of slave-made goods such as cotton and sugar, mobilizing thousands of women. Through their leadership other ordinary women began to see that despite not having a vote or a voice outside their homes, their actions and contributions were needed to end slavery in the United States.

I desperately wanted to connect with other women who had that same passion for our world today. I didn’t know what I was going to do about it or what it would look like in my life, but I refused to do nothing. I clenched the steering wheel with resolve. In the quiet of my car I became an abolitionist.

"Slave-Free."

I have come to believe that it is not by chance that I was born in the United States at this time in history. I have personal power many people in the world do not. I believe women like me—women with freedom, liberty and opportunity—have an obligation to speak into our generation on behalf of those in the world who do not have a voice: those targeted, exploited and held against their will.

I believe each of us has something meaningful to contribute in the fight against global slavery. Regardless of our age, circumstance and season of life, we all can do our part. We are good people in places of power, and as such we must work together with resilience, faith and courage. We must fight against indifference—the feeling that there’s nothing we can do about problems “over there.” We must claim our power to set the captives free.

Reflect

- Think about the idea of “good people in places of power.” What does this mean to you?

- In what ways are you a good person in a place (or places) of power?

![]()

2

We’ve Done This Before

Shayne Moore

The abolitionists succeeded because they mastered one challenge that still faces anyone who cares about social and economic justice: drawing connections between the near and the distant.

Adam Hochschild, Bury the Chains

Slavery isn’t new. The pursuit of wealth has resulted in the enslavement and exploitation of others since the beginning of time. Unlike in the past, however, slavery is now illegal everywhere in the world.

Even so, there are more people enslaved today than there were during the entire trans-Atlantic African slave trade that ran from the sixteenth to the nineteenth century. The widely accepted estimate of number of slaves in the world today is twenty-seven million people.[1] Eighty percent are women and children.[2]

Picture every person in Los Angeles, New York City and Chicago. Now picture them as slaves.

The institutionalized African slave trade we learned about in history classes has been abolished. Yet modern-day slavery is the fastest-growing criminal industry in the world, with profits of more than $32 billion—roughly the same as Exxon Mobil.[3] Companies the size of Exxon Mobil are eager for you to see them, and they are accountable to the regulation of the governments of their host countries. Modern-day slavery violates the laws of every country in the world, and the people who traffick other human beings are thrilled when nobody notices.

Criminals who engage in human trafficking have created a well-organized, elusive international market for the trade of human beings based on high profits and cheap labor. Pimps and mafia lords have figured out it is cheaper to sell a person than to sell a drug. A drug pusher sells a drug once; once it’s sold, he has to replenish his supply. A pimp or slave owner “sells” each woman over and over again, profiting again and again from the exploitation.

These realities are sickening and daunting. How do we wrap our hearts and minds around the reality that there are people suffering in slavery more now than ever in the history of the world?

We can be informed immediately of breaking news anywhere in the world. We sit at our TVs or computer screens and consume mass amounts of information daily. The challenge for good and thoughtful people of our generation is to not merely consume information but learn how to act and engage with what we learn.

You may have heard the terms “human trafficking” or “modern-day slavery,” but only in passing. “Human trafficking,” as we’ve learned, is the process of enslaving and physically moving a person against their will. It is the modern-day slave trade. The United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime defines human trafficking as

the recruitment, transportation, harboring, or receipt of persons by means of the threat or use of force or other forms of coercion, of abduction, of fraud, of deception, of the abuse of power or of a position of vulnerability or of the giving or receiving of payments or benefits to achieve the consent of a person having control over another person, for the purpose of exploitation. Exploitation shall include at a minimum, the exploitation of the prostitutions of others or other forms of sexual exploitation, forced labor or services, slavery or practices similar to slavery, servitude or the removal of organs.[4]

The U.S. State Department’s characterization of slavery, based on the Trafficking Victims Protection Act of 2000

- The recruitment, harboring, transportation, provision or obtaining of a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud or coercion, for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage or slavery. Evidence of these practices can be seen in agriculture, the restaurant business, mining, nail salons, hair-braiding businesses, domestic servitude and a variety of types of manufacturing.

- A commercial sex act induced by force, fraud or coercion, or in which the person induced to perform such an act has not attained eighteen years of age. Basically speaking, anytime someone is under eighteen years of age and is performing any commercial sex act, it is by law human trafficking. Force, fraud or coercion is not necessary to make it illegal.

- War children—these are children who are often stolen from their homes and forced to fight in tribal wars. This practice is mainly found in African countries such as Uganda, Ghana and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

“Modern-day slavery,” by contrast, is when an individual or group completely controls another individual or group, often using violence, for economic gain. Although there are slight distinctions between these terms, they are often used interchangeably.

In modern times international trading has become more accessible not only to legitimate global enterprises but also to criminals. Free markets enable us to own products from all over the world at affordable prices. Criminals have applied this same logic to the trading and selling of human beings. Two hundred years ago, when slavery was legal, slaves were seen as an investment; the average price for an African slave was $40,000. Today the average cost of a slave is $90. Slaves today are considered a disposable commodity.[5]

As I’ve wrestled with this issue I’ve often wondered, what can I do? I’m not a staffer at the United Nations or member of the State Department. I have no direct line to an embassy anywhere in the world where I can share my concerns. I might watch, read and pray, but t...