![]()

AMARANTE

![]()

CHAPTER 5

The plane banked and Virginie put down her book to look out of the window. They were still over the sea. How she loved that cobalt shade of deep water – just looking at it filled her with energy, with life, with hope. In the seat beside her, Jake napped, and she almost woke him to point it out, but then she checked her watch. Let him rest. They’d be seeing it up close very soon.

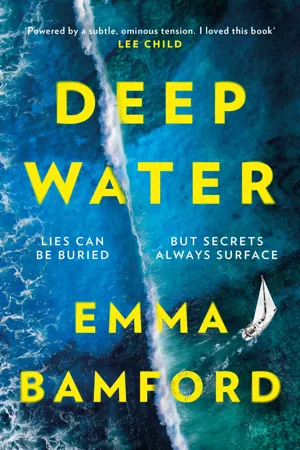

She unbuckled her seat belt and leaned as far forward as she could, straining for a glimpse of land. The height and speed of the plane had a peculiar effect on the waves below, seeming to fasten them in time and space, solidifying the whitecaps. She spotted a yacht, impossibly small. Both sails were up, and it was heeled over, so it must have been moving, but, like the waves, it seemed pinned in position on the earth. She wondered about the people on board – they were on a voyage, like her and Jake. Did they share the same dreams? Were they also seeking new beginnings? She pressed the tip of her finger against the windowpane. Ice crystals had formed on the outside.

Just before they started the descent, Jake woke, blinking groggily. ‘How long was I out for?’

‘Couple of hours. We’re nearly there.’ The huge smile he gave her mirrored her own feelings.

When they emerged from the controlled atmosphere of the cabin and started to descend the steps from the plane, the hot air brought enticing exotic smells: smoke, melting tarmac and a vital, vegetal spice of tropical land, so different from the air in England. She paused and took a deeper breath. Would everything else be so different here, too? She hoped so.

Her foot left the last metal step and found the ground. Ahead, a line of bottle palms, their fronds rustling in the wind, flanked the entrance to a low-slung terminal. Despite the fifteen-hour journey, she was buoyant. Just one more hour, two at the most, and they’d be there. She turned and waited for Jake, who was halfway down the steps, carrying a wheelie case that wasn’t theirs. On reaching the ground, he placed it in front of an elderly woman dressed in a long patterned tunic and head scarf. The woman thanked him in smiles and ducks of her chin. That was the thing with Jake: always thinking of others.

Virginie snaked an arm around his waist and leaned in. ‘Leaving me for another woman already?’

He puffed out his cheeks. ‘You’ve some stiff competition there.’ He kissed the top of her head, and together they followed the woman and the other passengers across the apron to the terminal.

It was late afternoon by the time the taxi stopped at the harbour. Waiters were preparing an outdoor restaurant for the evening’s customers, setting out plastic chairs, laying tablecloths, weighing down piles of whisper-thin pink paper napkins with forks and spoons. They nodded to her as they worked.

Jake unloaded their luggage from the car. ‘I’ll go find a water taxi to take us out to the boat,’ he said, adding the last holdall to the pile on the ground. ‘You okay to wait here with these?’

‘Sure.’ She pulled some ringgit from her purse. ‘Here.’ The notes she’d withdrawn at the airport were purple, red and orange, as colourful as money in a Monopoly set. ‘You might need to pay up front.’ He pocketed them, kissed her cheek, and set off.

Beyond the restaurant, the harbour brimmed with boats. Wooden longtails disturbed the tranquillity with the loud tut-tut-tut of their outboard motors as they returned from a day’s fishing. She pulled out her phone to take a picture. In the shot, the red and blue paint gleamed in the sunshine. With their almost vertical bowsprits, the longtails looked like tropical versions of Viking longships, back from plundering the seas, or the canoes of those other early seafarers, the fearless Polynesian explorers who set out on voyages thousands of miles long, trusting their fate to the winds and stars. She made a mental note to email her boss at the museum – former boss, really – and suggest he add something on Malay longtails to a display. She posted the photo, so her brother and sisters and their friends would see it and know they’d arrived safely.

At the far end of the sea wall the Malaysian flag fluttered on a pole, familiar and strange at the same time in the way it looked just like the Stars and Stripes until a hard snap revealed a yellow crescent moon and star in the canton. With the wind came the ozonic scent of the ocean, layered with diesel and the fishy stink of nets crisping under the sun, far more intense than the smells that blew in off the Solent back home. Beyond the sea wall about twenty sailing yachts were at anchor, all turned with the tide to point towards the shore. She scanned the bay, but it was difficult to tell which yacht was theirs from this distance, which would be their home – the first they’d owned together – as they travelled for the next year, perhaps even two. Her stomach flipped. Imagine the places these boats might have been, what their owners had seen. Soon she and Jake would be the ones with stories to tell. What better way to get their marriage off to a good start?

The sun was relentless, and she eyed the shade cast by a broad banyan tree. Strangler fig, some people called them. She shifted their four bags underneath its spreading canopy and examined the aerial roots that had grown down to the earth in search of water. Remarkable, really, how nature could thrive as long as it was able to fulfil its basic needs: food, water, light.

The luggage had already picked up a coating of dust. Their whole lives – their new lives – were held in these four bags. Packing up the flat had been a lot of work, but as she’d watched the storage van round the corner, its indicator barely visible through the autumn fog, she’d felt lighter. It was an odd word, belongings, for things like pots and pans, armchairs, winter boots, photographs. It implied you needed all those items to feel you belonged somewhere, or with someone, and that without all that stuff you were untethered, an outcast almost. But things, even people, weighed you down. Apart from Jake. He never could.

A cat approached, a tortoiseshell, and nuzzled her calf. It was an adult, fully grown but tiny, little bigger than a kitten, its tail bobbed. It mewed, and she went to scratch behind its ears, hearing Tomas – fleas, disease, unhygienic. She stroked the top of its head, under its chin. It pushed its skull against her fingers a couple of times before losing interest, distracted by some spilled yellow rice on the grass by her feet.

She edged along a few grains with her sandal. ‘Here, little fellow, have it all.’

At her name being called, she looked up. Jake was coming along the path, his hair streaked copper by the sun. ‘Good news. Found a fisherman to take us.’

They picked up two bags each, and he led the way down to the dock, where a longtail was waiting, a fisherman squatting by the tiller. Jake swung the bags into the boat and Virginie climbed in. The longtail’s narrow beam made it unstable, and it tilted alarmingly, causing her to land harder on the bench than she’d intended. Not very graceful. Embarrassed, she looked at the fisherman, but his hollow-cheeked face remained impassive. Once Jake was in, too, the fisherman yanked on the starter cord, firing the engine into a noisy rattle, and headed out into the bay.

The wind generated by the forward movement was a blessed relief, drying the sweat on her forehead and lifting her damp hair away from her neck. The fisherman, old, possibly as old as her father, but bony in his shorts and loose T-shirt while Papa was rounded by good living, pointed at one of the yachts anchored towards the back of the pack, and Jake nodded. As they drew closer, Virginie recognized the sail cover, but the boat looked more tired than the last time she’d seen it, the navy lettering of its name, Lost Horizon, faded to a stonewashed denim, furry algae clinging to the waterline. She shook herself mentally. None of that mattered, not really – it was just cosmetic. No need to focus on the little things; this was about the bigger picture. A bit of elbow grease, as Jake called it, and everything would be fine. And besides, the worn letters would soon be replaced when they renamed the yacht and put their own stamp on it.

The longtail drew alongside, and Jake stood and grabbed the rail, holding the two boats together.

‘Pergi, pergi,’ the fisherman said, raising his voice over the clatter of the engine, flicking his hand, signalling her to climb onto the yacht. She hefted their bags onto the deck and scrambled up, the scorching metal of the toe rail burning her knee as she went. Jake had only one foot on the deck, the other still in midair, when the fisherman pushed off and revved his throttle, eager to return home before the evening prayer.

As soon as she got below deck, she was sweating again. The air down here was oppressively still, so layered with the stink of months-old mould and fuel and brine that it was almost solid, and she struggled to breathe. Jake opened the hatch and windows, but it made little difference.

‘First job tomorrow, fit some fans?’ she asked.

He pulled off his T-shirt. His skin was an English-winter white all over, ghostly looking. ‘Definitely.’

Four months had passed since she’d spotted the online listing for the yacht. At thirty-six feet, it was the perfect size and setup for two, and such a bargain compared to what people were asking in the UK or Europe. She’d pointed it out to Jake, and a couple of weeks later, after an email exchange with the owners, an older Dutch couple, they’d found a good deal on plane tickets and flown out here to view it. They were confident that with Jake’s boatbuilding experience and her countless summers on board her father’s boat share they’d be capable of doing the survey themselves. They’d found the yacht in sound condition for its age, if, naturally, given their tight budget, a little worn. After a short negotiation with the Dutch couple, they’d transferred their savings.

She took a look around, squaring what she saw before her now with the mental pictures she’d held in her mind for the past few months. The blue bench-style settees, which ran along each side of the saloon, upright as church pews, were faded, but not yet in need of replacing. She opened the wooden cupboards above, welcoming the whisper of air against her cheek that the movement of the louvred doors created. It was a good job they hadn’t brought much stuff with them from home because it was a meagre amount of space, even compared to what they’d had in their small flat, and especially so compared to the wall of wardrobes she’d had in Paris. That bloody antique dresser of Tomas’s – it was so huge it had dominated the bedroom of that apartment. Although it was worth more than this entire boat, she’d gladly have given it away; if she’d been allowed to, she’d have stripped all of the fusty inherited furniture out of that place, ripped away the heavy drapes, replaced everything with clean, modern pieces – a chest of drawers or a bedside table she could put her hairbrush onto, or her glass of water, without fear. But that hadn’t been her choice to make.

She closed the doors with a snap, shutting out the past. The walls were bare now the previous owners had taken down their things, leaving her free to decorate any way she chose. She pictured herself hanging mementos bought from beachside villages, collecting shells from every anchorage they visited, curating the tale of their travels. Tomorrow she’d pick up a local batik print to jazz things up.

The polished sole boards were smooth under her bare feet as she turned towards the back of the boat, into the narrow L-shaped galley that hooked around the starboard side. She opened the top-loading fridge, peered into the cupboards, tried the small gimballed stove. All were still in good working order. The sink was rusting where the saltwater tap had been allowed to drip, but a good scrub would get the marks out. Two paces beyond the galley was the cabin, with a high double berth. Not as wide as their bed at home, but big enough, cosy for two.

She retreated back through the galley on her way to the head on the port side. Jake was at the chart table, kneeling on the seat, flicking switches on the instrument panel. As she squeezed through, the boat rolled, riding the wake of a passing vessel, and she grabbed his calf to steady herself. She’d need a day or so to find her sea legs.

‘I think the batteries are dead,’ he said, clicking away. ‘I swear they were working last time we were here.’

The Dutch couple had left the head in a fairly clean state, she found when she ducked into the compact bathroom. She pulled the shower hose from its slot at the sink, where it doubled as a tap, and turned it on. Only a dribble. What she’d give for a cool shower – but no power meant that wasn’t an option right now. It was cramped in there, and all at once she was too hot. She backed into the saloon and unzipped one of her bags, grabbing the first pair of shorts and loose T-shirt she could find. As soon as she lifted her hair from her neck to twist a band around it, she could breathe.

She rooted around the bag again, looking for the folder with their wedding photo. She’d only brought the one – her and Jake, a selfie taken by the river, their faces filling most of the frame in front of a tufted sky. She propped it on the shelf.

‘Damn it,’ Jake said, giving up at the panel. The bottle of champagne she’d bought at duty-free was sticking out of her bag. He fished it out. She’d blown their daily budget on it but hadn’t cared. ‘Just this once,’ she’d told him as they stood under the artificial 24/7 lights of the airport shop as people milled past, all on journeys to somewhere else. ‘It’s a special occasion.’

‘We can’t chill it,’ he said now. ’The celebrations are going to have to wait a day or two.’

She knew other ways to celebrate. She moved over to him. His chest was slick and the hair at his nape damp under her fingertips. He was salty when she kissed him, tasted of home.

‘Think it might be too hot for this?’ she said.

‘Baby, it’s ne...