![]()

1.

PATROLLING THE WORLD’S LONGEST FENCE

Western Australia’s 1100 Mile Rabbit-Proof Fence

If it please you, accompany Millie and Curly and me on a patrol of one section of 163 miles of the longest fence in the world, the Number One Rabbit Fence, Western Australia. The purpose of such a fence, of which there are many in Australia, is to stop the migration of rabbits to the wheat belts. This particular fence begins at the edge of a water-washed rocky jetty facing the Southern Ocean, near Hopetoun, and it runs northward for 1,130 miles to end at a salt-water creek near Banningarra, on the North-west coast.

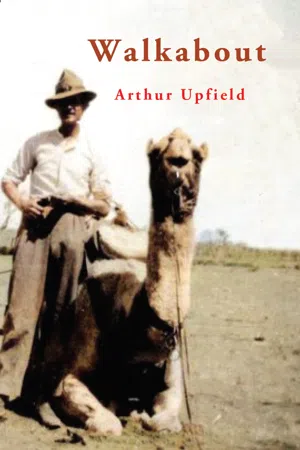

Millie and Curly are camels, almost akin to the elephant in intelligence, swayed by the human emotions of joy and anger controlled by a “homing” instinct almost as strong as that of the pigeon, at times placid and at other times as petulant as children. They are harnessed in tandem to a large, covered dray, which, when not drawn by them, is kept level with drop-sticks to provide the boundary rider with a one-room house on wheels.

At the northern extremity of the section, from which end the monthly patrol is made, is the Government Camel Station named Dromedary Hill, so called from the twin-backed, stony hill in the vicinity of the homestead. The man in charge comes with us the short distance to the fence through which we must pass to reach the narrow track flanking the fence on its east side for many hundreds of miles. Millie, the team leader, is turned to the south, and, when clear of the gate, the dray is stopped while au revoirs are exchanged by men who may not see another human soul for ten days or a fortnight.

Here we are able to view the fence and the track that form what is known as a cut line—a line first surveyed and then cleared to a width of twenty feet, the fence being then erected two feet west of the centre.

Northward the cut line dwindles to infinity in the dark mulga scrub. Excepting for a few angles to escape “break-aways” the cut line is rule straight.

Southward, the line narrows to a ribbon at the summit of a long rise nearly two miles distant, and beyond that rise, 161 miles away, is the small wheat town of Burracoppin on the main railway line from Perth to Kalgoorlie, which marks the southern extremity of this section. The fence runs a further 218 miles beyond the railway line to the Southern Ocean, whilst in the opposite direction it shears through the bush to the Indian Ocean, 750 miles distant.

We have to cover 326 miles before once again we see Dromedary Hill. Twenty-eight days the journey will occupy, and we will travel with the time-table regularity of trains. Down in Burracoppin, or wherever he may be, the inspector will know every evening where his riders are, or ought to be, camped.

Millie swings along, her tread cat-like and silent, placidly chewing her cud and quite resigned to the month’s exile from all her friends and relatives at the station, but Curly, between the shafts of the dray, is not so resigned. He is, in fact, openly rebellious. He vents throaty growls, and endeavours to turn himself into the letter S in order to look back at those of his comrades that have come to the fence to watch us away, for be it understood that he wears winkers like any old dray horse.

Soon the homestead and the barren hills behind it are shut out by the bordering scrub. On the long slope, the wheels hiss softly in the deep, dry sand. The everlasting fence-posts slip by in endless procession.

We pass our first wooden mile-peg marked M/162 with the broad arrow beneath the numerals. Looking back and down the straight track, we can see a tiny dot midway between us and the vanishing point of the cut line. That dot is the Camel Station overseer, watching us until we disappear from his sight over the rise but a short distance ahead. On the summit of the rise, the sand on the track is replaced with surface ironstone rock. Here the scrub trees thin out and give growth to the soft, pearl-grey flannel-bush, the salt-bush and the blue-bush, and the world-famed Western Australian everlasting flowers.

Round then the first angle of the fence at the 161-mile peg, to continue a further mile when the fence in turn forces us a trifle eastward.

There is no obvious reason why these angles should be made, but in all cases the real reason is that they are made to escape the precipitously faced break-aways. The dray wheels rumble hollowly over the surface rock, giving Curly a grand excuse to pretend to be frightened. As he is easily able to pull the dray himself without exertion, the brake is applied and he is given work to do.

To our right, through a veil of tree-branches, looms the sheer face of a Western Australian break-away caused in some far geological age by the subsidence of wide sections of the earth’s crust. From here the track falls sharply at first, and then more gently in a perfectly straight line across comparatively open country to stab the heart of the bush spreading to the level, knife-edged horizon. The break-away cliff of red ironstone rock sweeps in a giant arc westward and then southward, appearing like the face of a great quarry, its summit fringed with scrub trees, its foot put down on white sand dotted with salt-bush. On the track, and out from the bordering bush, particles of mica reflect the sunlight from a billion points coloured white and gold and amber.

Down the stony slope, with hand on brake and eyes on the fence to detect a broken wire or a rent made in the netting by kangaroo or emu, we are hurried by the impetuous Curly, who would so like to break into a tearing gallop for a full mile—and then lie down for two or three days to get over it. When level ground is reached, the brake may be left alone, but never beyond jumping distance. It is astonishing how quickly a camel can spring into a gallop from a slow walk.

At length we reach the dense scrub, where no longer do the light of day and the reflection of the sun by the mica particles make buoyant our spirits. On both sides of the cut line, shadows fall between the trunks of living trees to the trunks and debris of dead timber. Save for a few crows that will follow us from camp to camp for many miles, and the ever-watching wedge-tailed eagles, mere specks against the sky, the world seems empty; it seems so, but is not really so.

Having of necessity left the Camel Station late this morning, we select our camp near the 156-mile peg, where the scrub provides a variety of food for the camels. A camel will not long eat of one kind of bush or tree leaf, and it will never eat grass, which is as well, because we shall see no grass until the farms are reached. It demands variety, and, if variety is not to be obtained, it will go hungry. Its habit is to wander from bush to tree, snatching a mouthful here and there and ignoring fodder on either side.

The dray is drawn just off the track. The wheels are chocked and the drop-sticks let down to ensure its level position after Curly is taken from between the shafts. Having been unharnessed, the camels are short-hobbled and permitted to roam.

This section of fence is the hardest of any for animals expected to live on the country. Its northern end at the Camel Station reaches the southern extremity of the pastoral country proper, and between that place and the salmon-gum country, first entered at the 60-mile post, extends a hundred-mile-wide belt of desert scrub, of low, tough bogeta and broombush, whereon no camel or horse or donkey will long maintain condition.

As there are no cross fences from one end of the section to the other, and as the camels will ever make back to the land of their birth, once they get away from the rider, he will be lucky to overtake them before they reach the Camel Station gate.

As they cannot be trusted to camp for the night at even one of the few good camel camps, it is necessary along this section to cut bush and drag it to selected trees, to which they are secured with long neck ropes that permit them to lie down. At one time a rider lost his camels at the 69-mile peg and was obliged to walk back to the 163-mile peg to get them again. One eats from a drop table in the dray to escape the ants. Save only when it rains, one sleeps on a Coolgardie stretcher set up beside the dray. At dawn, when the camels simultaneously get up, the clatter of their bells announces the new day. Before we dress, the mound of grey fire ash is broken open to reveal the red wood coals, on which is placed the billycan containing the remains of last night’s tea; and, when the camels have been freed to find their breakfast, ink-black tea is sipped and a cigarette smoked. The sky is ever of interest as a weather prophet, excepting during the winter months when rain-bearing clouds often sweep across the clear sky without a heralding sign.

After a simple breakfast of bacon and damper and milkless tea, we pack all gear into the dray, and then, perhaps, a couple of posts are cut to replace posts which have become rotten. Every year hundreds of new posts are put in.

To-day we cross a spinifex plain—semi-globes of spiny bush covering the brown earth like large, green meat-covers.

Beyond the plain, we again enter the mulga timber, with the track and the fence dwindling to infinity ahead until we are able to see the blank wall of scrub at the angle marked by the 148-mile peg. Time drags before we reach the turn, and, having swung round it, we again see the fence dwindling to infinity amid the silver leaves of the broad-leafed mulga.

There is work to be done south of the 144-mile peg, where there is a rain-shed—a simple roof of corrugated iron from which rainwater is piped into two large receiving tanks beneath it. There are several of these rain-sheds on this section constructed for the fence-rider and his camels, and sometimes thoughtless and unauthorized travellers leave a tap running with the consequent waste of hundreds of gallons of precious water on which life itself depends.

Curly makes known his desire for a drink when within a quarter of a mile of the rain-shed. He strains against braked wheels, his haste objected to by Millie, who vents low rumbles of protest. Two hundred yards from the water, the dray is drawn off to the side of the track, because round about the rain-shed there is no wood for cooking and there is a super-abundance of ants.

At five-thirty the two drinking buckets are taken from the dray with purposeful noise. At once the bells strapped to the necks of the camels feeding deep in the bush cease their pleasing tinkle.

The buckets, continuing to be loudly rattled, are taken to the water tanks, when from a distance again comes the rhythmic tinkle quickly becoming louder until the two grey shapes appear at the edge of the scrub to hasten to the filled buckets as quickly as hobbled feet will permit.

Some twenty gallons of water they drink between them. For a little while they stand with legs wide apart, eyes bright, long, split upper-lips waggling. They begin to chew their moistened cuds with vivid enjoyment, content for an hour, but for an hour only, when the desire to return “home” will seize on them.

They have wandered half a mile before they are brought back to the supper prepared for them against the trees to which they are to be tied for the night. Millie is a little vexed at being thus frustrated. Curly is angry and stubborn. Now and then he lies down and bellows like a small child who refuses to walk another yard. Tempers, however, are banished by sight of the prepared supper, when Millie wants to kiss the driver and Curly wants to jump on him.

Routine governs life on the fence. Mental cobwebs cannot be spun. One may take chances with horses or bullocks, but one cannot take chances with camels and long survive. Millie may be trusted a little. Curly may be trusted not to kick with his hind feet and strike with his fore feet, but, when he is being harnessed, his head must be roped close to a tree trunk, and when at work he must not be trusted for a second.

In answer to the oft-put question: “Are you not terribly lonely?” one must answer: “There is no time to be lonely.” In one week a fence-rider will read more than the average city man will read over a full year, while his reading will be infinitely more varied. The only part of the life that palls is those windless periods, when for days and nights not a leaf stirs in country where there is but little bird life and no animal life. When the wind is first heard in the distance, roaring across the top of the scrub, one feels inexpressible relief.

Once I had a dog for a companion; but it picked up an old strychnine bait and, despite all efforts, it died in my arms. At another time I took with me a cat that I came to love much, and then Curly stamped on her when she only wanted to rub herself against his dinner-plate foot. I took a young galah. It used to ride all day in the dray and it never knew the bars of a cage. At night, when reading or writing in the dray by the aid of a hurricane lamp, should I be irritated by the visit of a tree moth or a flutter-ing bat, the galah perched on one shoulder would murmur sleepily: “You old devil!” Then one morning, when returning to camp with the camels, I heard a scream of defiance, and, on looking up, was in time to see my bird in the talons of a swiftly-rising hawk.

After that I gave up companions on a rabbit fence. Their loss incurs too much heart-break.

At the 135-mile peg the timber is scattered and the ground is a vast, unbroken carpet of white and gold and blue splashes of colour made by the myriads of wild flowers. Each nodding head is supported on a long stem rising from tiny leaves lying flat on the ground. Weeks after the leaves have perished the flowers remain. In this amazing garden we camp for noon lunch, and while we are eating it in the dray, a bird settles on a fence post to watch us. The world is hushed, and the only sounds are made by the cud-chewing camels and a few blowflies. Presently, at a great distance, one hears belled camels coming our way. The bells grow ever louder exactly as though the camels, or it might be bullocks, are being brought into camp. Done by the entertaining ventriloquist on the post—the bell-bird!

At the 96-mile peg there is a rain-shed and hut combined. Here, in the centre of the great belt of desert bush is an oasis of salt-bush, wait-a-bit, and native peach trees, growing between gnarled red gums. From this splendid camp we go on to the 82-mile peg—where the fence and track passes through a wide gap in a line of break-aways about which the lightning plays its tricks. A poor camp this. There are many deviations in the fence between this peg and the 69-mile peg from where we turn off into the bush to reach a small hut built in a natural clearing. The clearing is surrounded by wattle trees blazing with heavy, yellow bloom, and the ground on which they grow is snowed deep beneath the white everlasting flowers. A garden, a bush garden, that imperishably burns itself on the mind.

We are in the salmon-gum forest when we pass the 60-mile peg. The tall, straight, lovely trunks of these trees gleam pale against the dark-green background of the lesser bush, and like all gum-trees they shed their bark in preference to their leaves.

We come now to the northern wheat farms in process of creation. The “chop-chop-chop” of biting axes and the whirr of tractors distract us. A mighty heave at the dray, and we are off at a gallop, the rider clinging to the brake-handle protruding from the rear of the vehicle. A settler's wife and children are running through the bush to see their first camels outside a zoo—and the camels are made fearful by the coloured, swaying skirts to which they are quite unaccustomed.

I should glory in Australia’s development. Alas, the sound of thudding axes and the splintering crash of falling forest giants both anger and sadden me.

Day by day we pass the endless fence-posts, repair broken wires, and patch the netting torn by the farmers’ machines and trucks. In one day we have emerged from the bush proper to the farming districts, where we meet modern road traffic and where it is never silent. We have no place in the world of machinery, this world of cleared spaces not natural to our beloved bush. Perhaps of the three of us, Curly dislikes it least, for it provides him with unlimited excuses to play the fool. At the 25-mile peg we cross the loop railway line at Campion, and thereafter travel nine miles over an established wheat-belt to reach, and pass through, poor ironstone country until, finally, we step on to the main highway from Perth to Kalgoorlie skirting the railway.

The line, of course, breaks the fence; but here it crosses over a deep pit that presents as great a barrier to rabbits as does the fence itself. Beyond the line the mile-pegs begin again at Number One, and across the line we bump and clatter to reach the Government hay farm, where the camels will rest for two days. One mile west lie Burracoppin and the boarding house, where may be eaten fresh yeast bread and butter, celery and red steak for which the body craves after a month’s subsistence on tinned food, bacon, and baking-powder bread.

Neither the driver nor the camels are happy here at Burracoppin, and we are emphatically pleased when our faces are again turned northward. Even the desert bush country to us is better than this.

Reaching at last the summit of the rise at the 161-mile, there, falling away from...