![]()

1

Religion

Study and Practice

World Population: 7 billion[1]

Professing Christians: 2.1 billion

Religious Non-Christians: 3.7 billion[2]

What would you say to someone who has no understanding whatsoever of the concept of religion? In the story The Master Key, science-fiction writer Poul Anderson made this matter a question of life and death.[3] A group of human traders on the distant planet Cain encountered an alien race, called Yildivans, with catlike features and attitudes. Like all felines, they were only willing to relate to people on their own terms. For them these terms included that humans must be as free as they were; otherwise they would be on the level of domestic animals, whose lives were expendable. Eventually the Yildivans realized that even the people with the highest level of authority paid homage to an “owner” called God, and the best efforts to try to explain religion to the Yildivans failed to correct the impression. Deeply offended, the Yildivans decided that the traders must be killed. What would you try to say under such circumstances?

Providing a definition for the term religion is challenging, even when you are not under duress from some fictional race of aliens. Let us start out by looking at a few diverse examples of religion. Frequently, religions involve gods and spirits, but not always.

There are many commonly used words in the English language that elude a single definition. Take the word ball. We can play soccer with one; we can see Cinderella dance at one; we can also have one in a more figurative sense: exchanging funny stories with a friend. We may say that in basketball the center of attention is a ball because it is round and can be played with. We may hear people refer to the sun as a great big ball, meaning that it is round, but we cannot play with it. Conversely, the object used in American football can be played with, but it is not round; nevertheless, we say that it is a ball. In short, the word does not have a single definition that covers all aspects of its use. However, we rarely have trouble identifying what people mean when they use the word ball.

We can picture a Friday prayer service in a mosque—the house of worship of Islam. The men of the community have assembled and are sitting in loose rows on the rug-covered floor in front of a pulpit from which an imam preaches instructions on how to live a life that is pleasing to God. At the end of the sermon the believers stand up, forming exact rows that face the niche at the front of the hall that points in the direction of Mecca. In unison they go through the prescribed postures of standing, bowing and prostrating themselves as they recite their prayer of devotion. This picture confirms the common notion that religion focuses on the worship of God.

Now let us picture a Japanese Zen master addressing a group of American college students. “Look beyond words and ideas,” he tells them. “Lay aside what you think you know about God; it can only mislead you. Just accept life as it is. When it rains, I get wet. When I am hungry, I eat.” Is this religion?

Mary, an American college student, is not affiliated with any organized religion; in fact, she blames religion for much of what is wrong with the world today. But she is full of high ideals and has committed her life to the service of humanity. After graduation she plans to spend a few years in the Peace Corps and then reside in a poverty-stricken area of America where she can assist disadvantaged people in learning to lead a better life. In order to carry out this task to its fullest, Mary is already limiting her own personal belongings and is not planning to get married or raise a family. Could it be that, despite her assertion to the contrary, she is really practicing a religion?

The word religion functions in somewhat the same way. To a great extent it conjures up definite concepts when someone utters it. We may think about groups such as Buddhism, Christianity or Islam, or ideas such as worship, gods, rituals or ethics. It is extremely unlikely that anyone would associate religion with baseball, roast beef or the classification of insects. However, it is quite difficult to come up with a definition of religion that includes everything we normally associate with religion and excludes everything we do not consider religion.

For example, a definition focusing on gods, spirits and the supernatural may be too narrow. There are forms of Buddhism (for example, Zen) that consider any such beliefs to be a hindrance to enlightenment. Yet, are we prepared to deny that Buddhism is a religion? I think not.

This difficulty may lead us to define religion more broadly because even where there is no direct worship of a god or gods, the religion still supplies values that give life meaning. This aspect is certainly true for Buddhism, which definitely supplies values for life. But is it legitimate to turn this assessment around and say that wherever someone is committed to a set of core values that give their life meaning, they are practicing a religion? If so, then Mary, the woman who is devoting her life to the service of others, could conceivably be considered as an example of someone practicing a humanistic religion. However, a member of an organized crime group may also follow some values, albeit very different ones: money, domination, power and so forth. Surely we don’t want to call observing the standards of organized crime a “religion.” It does not follow from the fact that religion supplies core values that wherever there are core values, there must be a religion.

In order to qualify as religious the core values may not just be a part of everyday life, such as accumulating a lot of money, regardless of the means, even if they are an important part of someone’s life. I consider it to be important that I brush my teeth every day, but that fact does not make me an adherent of the tooth-brushing religion. Some guy may focus his entire life on the pursuit of wealth, but metaphors notwithstanding, that fact does not imply that earning money is his religion; in fact, other people may be more likely to point out that such a person is going counter to an accepted understanding of religion. Whatever the core values of everyday life may be, they cannot give meaning to life if they are just a part of life itself. In order to qualify as “religious,” the values must come from beyond the details of ordinary life.

The feature of religion that directs us beyond the mundane is called “transcendence.” Transcendence can come to us in many different ways, through supernatural agencies or through metaphysical principles (for example, the greatest good or the first cause), an ideal, a place or an awareness, to mention just some of the possibilities. Thus, we can start with a tentative definition for the moment: A religion is a system of beliefs and practices that directs a person toward transcendence and thus provides meaning and coherence to a person’s life.

And yet this definition may still need refining. Let us return to Mary, our idealistic person who is dedicating her life to the service of humanity. By her own statement she does not want to be classified as religious, though, in the way that people talk today, she might be willing to accept the notion that even though she is not religious, she exhibits a certain amount of “spirituality.”

Not too long ago a person would have been hard pressed to try to make such a distinction plausible. Doesn’t one have to be religious in order to be spiritual? How can it be possible to have faith without belonging to one of the traditional faiths? But those questions are no longer irrelevant, let alone meaningless. At least in a Western, English-speaking context, this distinction has become important. I remember not too long ago seeing an interview with a well-known actress on television, in which she declared that she was not religious but that she believed in a deep spirituality, which became apparent to her particularly as she gazed into the eyes of animals. (This book will not try to make sense out of such observations.)

So, to become a little bit more technical, what could be the difference between religion and “spirituality”? The answer is that religion also involves some external features, no matter how small, which have meaning only for the sake of the religious belief and would be unnecessary in other contexts. We are going to call this factor the cultus of the religion. For example, contemporary Protestant Christianity in the United States is associated with a specific cultus. In general, believers gather on Sunday morning in specially designated buildings, sit on chairs or benches (rather than kneel), sing special songs either out of hymnals or as projected on a screen, pray with their eyes closed, and listen to a professional minister speak about a passage in their holy book, the Bible. These items are not meant to be obligatory or an exhaustive description, but they are typical for the American Protestant Christian cultus. The point is that religion comes with a cultus, whereas spirituality is a purely personal and private matter that need not show up in any external manner.

So, let us make one more amendment to our definition of religion: A religion is a system of beliefs and practices that by means of its cultus directs a person toward transcendence and, thus, provides meaning and coherence to a person’s life.

This definition surmounts the difficulties I pointed out earlier. Needless to say, it is still very vague, but that is the nature of religion.

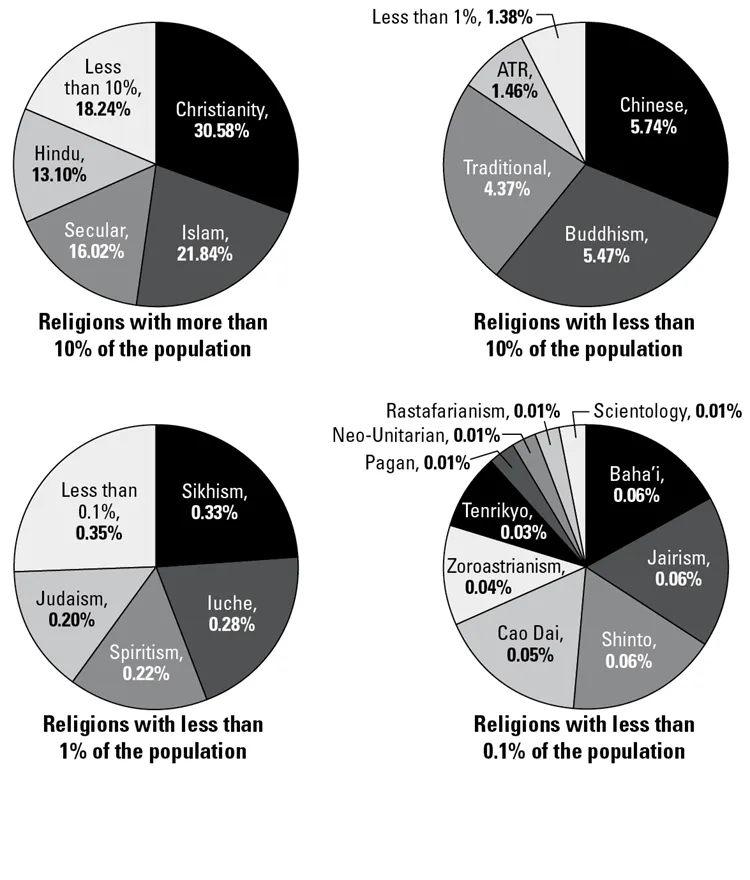

Figure 1.1. Religions and their percentages (based on data supplied by Adherents.com)

The Origin of Religion

Now let us return to one small remark that I have already mentioned in passing, but that carries a whole lot of weight for the sake of understanding religion, namely, that some of the features incorporated in the cultus of a religion have no purpose other than to be a part of the religion. This recognition implies that religion has a purpose all its own; it somehow stands out from ordinary life without religion. Presumably a religious person and a nonreligious person would paint a house in the same way. They would bake bread or hunt a deer with the same technique. Or, alternatively, if there is a difference between how the religious and the nonreligious person carry out these tasks, most likely it is that the religious person is adding certain actions, such as praying, which do not actually contribute anything practical to the process of painting, baking or hunting. Consequently, it would appear that complying with religious practice is not something that is necessary for the survival of human beings, and thus it raises the question, How could something that does not add to the viability of human life become such an important part of human culture? Or, in short, how or why did religion originate?

A century ago this question was a popular topic of debate. Today it is not addressed directly very often, even though the positions that were debated so hotly in earlier times are nowadays simply assumed by many scholars as they study various religions. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries many people spent a lot of effort trying to establish both the historical and psychological roots of religion. Frequently they intermingled these two areas in order to uncover how religion originated. They combined the data derived from whatever evidence there might have been with their theoretical assumptions of what must have happened. The evidence, as we shall discuss, was ambivalent at best for most of the theories, but we can see with hindsight how the theories were allowed to shape the evidence so as to make them as convincing as possible.

Let us take a look at the results of the work of many scholars. We can do so by differentiating between the subjective assumptions underlying these theories and the models that arose as a theory and evidence were combined. One of the features that these theories have in common is that they ultimately try to give a psychological or sociological interpretation of religion, which makes religion purely an attribute of human culture and thereby attempts to repudiate the reality of the supernatural.

Assumptions Underlying Theories of Religion

Subjective theories. Here are some of the psychological theories that motivated scholars to look for a naturalistic explanation of the origin of religion. The idea is that by showing how religion fulfills a specific psychological need, any further ground to believe in the truth of religious beliefs has been eliminated. Note that such thinking represents rather fallacious reasoning. There are many subjective needs and feelings that a person may have that do not rule out the reality of the feelings or of the object that fulfills the needs. For example, feeling hungry is a subjective experience, but that fact neither repudiates the meaningfulness of the feeling nor the reality of an object, namely, food, to fulfill that need. So, regardless of the truth or falsity of some of the theories I will mention, neither case would either invalidate the reality of religions or the need to discover a historical beginning of religion.

1. The nineteenth-century theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher contended that religion begins with a feeling, not a set of beliefs.[4] Specifically, he pointed to a universal feeling of “absolute dependence.” All human beings have this feeling, and since a feeling of dependence demands that there is something to depend on, the feeling is expressed in terms of depending on an Absolute, which is God. Note that this sequence proceeds from the feeling of dependence to the idea that there must be an object of dependence, not from the idea that there is a God to the idea that we depend on God.

2. Somewhat later, philosopher Ludwig Feuerbach promoted the theory that the concept of God is actually a combination of idealized human traits.[5] Human beings have the characteristics of love, power and knowledge (among others). An idealized picture of the human species would turn these traits into unlimited characteristics, producing a being with unconditional love, unrestricted power and all-exhaustive knowledge. This contrivance of an idealized human being is then called “God.” Thus, in the final analysis, a person who worships God is really worshiping an idealized self-image.

3. The psychological dimension of the human-centered approach to religion was broached by Sigmund Freud.[6] In his explorations of the human subconscious he thought that he had discovered the basic human need for a father image. Since human fathers are imperfect, even at their best, people substitute an idealized father image that they refer to as “God.” This notion is enhanced by the presence of an “oceanic feeling.” Just as we may be awestruck by the size, depth...