![]()

1

The Bible as the Story of Redemption

OUR OBJECTIVE AS CHRISTIANS IS TO UNDERSTAND the story of redemption, the Bible. More than anything else, we want to hear the words of the biblical writers as they were intended and claim their epic saga as our own. To accomplish this, we need to get past the great barrier—that chasm of history, language and culture that separates us from our heroes in the faith. In this first chapter we take our first step across the great barrier by addressing what I believe is the most profound distinction between “us” and “them”: culture.

Regarding the average human’s awareness of their own culture, career anthropologist Darrell Whiteman has said that “it is scarcely a fish who would discover water.”1 This is a reliable statement. Humans, rather than recognizing the trappings of their own culture (and that their culture may in fact be very different from someone else’s), tend to assume that other societies are just like their own. This is known as ethnocentrism and is a human perspective that is as old as the hills. As regards the Christian approach to the Old Testament, consider for example the standard depiction of Jesus in sacred Western art. Jesus is repeatedly portrayed as a pale, thin, white man with dirty blond hair and blue (sometimes green) eyes. His fingers are long and delicate, his body frail and unmuscled. Mary is usually presented as a blond. In medieval art, the disciples may be found in an array of attire that would have rendered them completely anomalous (and ridiculous) in their home towns. I am reminded of the famous “sacred heart of Jesus” image in which Jesus is, again, frail, pale, light-haired and green-eyed, and Marsani’s Gethsemane in which the red highlights of Jesus’ hair glow in the light from above, while his piano-player hands are clasped in desperate prayer. These portrayals are standard in spite of the fact that we are all fully aware that Jesus was a Semite and his occupation was manual labor. So shouldn’t we expect a dark-haired man with equally dark eyes? Certainly his skin would have been Mediterranean in tone and tanned by three years of constant exposure to the Galilean sun. His hands would have been rough, probably scarred, definitely calloused; his frame short, stocky and well-muscled. So why is he presented in Christian art as a pale, skinny, white guy? Because the people painting him were pale, skinny, white guys! We naturally see Jesus as “one of us” and portray him accordingly. This is not necessarily a bad thing. Rather, our close association with the characters of redemptive history allows us to see ourselves in their story. And this is as God would have it. But to truly understand their story, we need to step back and allow their voices to be heard in the timbre in which they first spoke. We need to do our best to see their world through their eyes.

The flip side of ethnocentrism is a second tendency I have come to speak of as “canonizing culture.” This is the unspoken (and usually unconscious) presupposition that the norms of my culture are somehow superior to the norms of someone else’s. Like ethnocentrism, this tendency is also as old as the human race. And in case you are tempted to think that the members of your culture have evolved past these sorts of presuppositions, let me counter for a moment. As an American, I spent most of my life simply assuming that democracy was somehow morally superior to monarchy, that bureaucratic cultures were more sophisticated than tribal cultures and that egalitarian relationships were more “advanced” than patriarchal. Why? Because these are the norms of my culture and I naturally saw them as “better than” the norms of others’. In fact, until challenged, I would have been hard-pressed to even separate the norms of my culture from my values or beliefs. Consider, for example, the early European and American missionaries who wound up exporting not only the gospel but Western culture as they spread across the globe. The New England missionaries to Hawaii are an example made famous by James Michener’s novel Hawaii.2 Here, as the Hawaiians converted to Christianity, they were subsequently also converted to the high-collared, long-sleeved, long-skirted uniforms of the missionaries. Petticoats and suit jackets for a seagoing people living in an island paradise! Why? Because these valiant missionaries were unaware of the distinction between the message of the gospel and their own cultural norms. They had “canonized” their own culture such that they saw their Western dress code as part and parcel of a Christian lifestyle. For the same reason, my senior pastor back in the 1980s would not allow my youth group to listen to Amy Grant or Petra. As their youth leader, I was instructed that if the kids wanted to listen to contemporary Christian music, they could listen to Sandi Patty. Why? It had nothing to do with the message or lifestyle of the respective musicians (my senior pastor did not actually know much about Amy Grant or Petra . . . or Sandi Patty for that matter). It was because Sandi Patty sang slowly, she sang soprano and she had no drums in her accompaniment. In the mind of my senior pastor, her music was “holier” than her more percussion-driven contemporaries because it was similar to the music of his youth and the music that inspired him to faith. My senior pastor, like most of us, was having trouble separating culture from content. But history proves to us that it is impossible to diagnose any human culture as fully “holy” or “unholy.” Human culture is always a mixed bag; some more mixed than others. And every culture must ultimately respond to the critique of the gospel.

As we open the Bible, however, we find that the God of history has chosen to reveal himself through a specific human culture. To be more accurate, he chose to reveal himself in several incarnations of the same culture. And, as the evolving cultural norms of Israel were not without flaw (rather, as above, there was a mixture of the good, the bad and the ugly), God did not canonize Israel’s culture. Rather, he simply used that culture as a vehicle through which to communicate the eternal truth of his character and his will for humanity. We should not be about the business of canonizing the culture of ancient Israel, either. But if we are going to understand the content of redemptive history, the merchandise that is the truth of redemption, we will need to understand the vehicle (i.e., the culture) through which it was communicated. Thus the study of the Old Testament becomes a cross-cultural endeavor. If we are going to understand the intent of the biblical authors, we will need to see their world the way they did.

The Word Redemption

But even as we attempt this first step of our journey into the Old Testament, we crash into the great barrier because the very term redemption is culturally conditioned. It had culturally-specific content that we as modern readers have mostly missed. In fact, redemption is one of several words I have come to refer to as “Biblish”—a word that comes from the Bible, is in English, but has been so over-used by the Christian community that it has become gibberish. So let’s begin our crosscultural journey with this word: What does the word redemption mean, and where did the church get it? The first answer to that question is obvious; the term comes from the New Testament.

Blessed be the Lord God of Israel,

for He has visited us and accomplished redemption for His people. (Lk 1:68)

Knowing that you were not redeemed with perishable things like silver or gold from your futile way of life inherited from your forefathers, but with precious blood, as of a lamb unblemished and spotless, the blood of Christ. (1 Pet 1:18-19)

Christ redeemed us from the curse of the Law. (Gal 3:13)

Okay, so the word comes from our New Testament, but what does it mean? And where did the New Testament writers get it? A short survey of the Bible demonstrates that the New Testament writers got the word from the Old Testament writers. The prophet Isaiah declares,

But now, thus says the LORD, your Creator, O Jacob, and He who formed you, O Israel, “Do not fear, for I have redeemed you; I have called you by name; you are Mine!” (Is 43:1)

And where did the Old Testament writers get the word? Contrary to what we might assume, they did not lift it from a theological context. Rather, this word and the concepts associated with it emerged from the everyday, secular vocabulary of ancient Israel. “To redeem” (Hebrew gāʾal) in its first associations had nothing to do with theology, but everything to do with the laws and social customs of the ancient tribal society of which the Hebrews were a part. Thus if we are to understand the term—and what the Old Testament writers intended when they applied it to Israel’s relationship with Yahweh—we will need to understand the society from which the word came.

Israel’s Tribal Culture

Israelite society was enormously different from contemporary life in the urban West. Whereas modern Western culture may be classified as urban and “bureaucratic,” Israel’s society was “traditional.” More specifically it was “tribal.”3 In a tribal society the family is, literally, the axis of the community. An individual’s link to the legal and economic structures of their society is through the family. As Israel’s was a patriarchal tribal culture, the link was the patriarch of the clan. The patriarch was responsible for the economic well-being of his family, he enforced law, and he had responsibility to care for his own who became marginalized through poverty, death or war. Hence, the operative information about any individual in ancient Israel was the identity of their father, their gender and their birth order.4 This is very different from a bureaucratic society in which the state creates economic opportunity, enforces law and cares for the marginalized. In fact, in a bureaucratic culture the family is peripheral—not peripheral to the values and affections of the members of that society, but certainly peripheral to the government and economy. In Israel’s tribal society the family was central, and it is best understood by means of three descriptive categories: patriarchal, patrilineal and patrilocal.

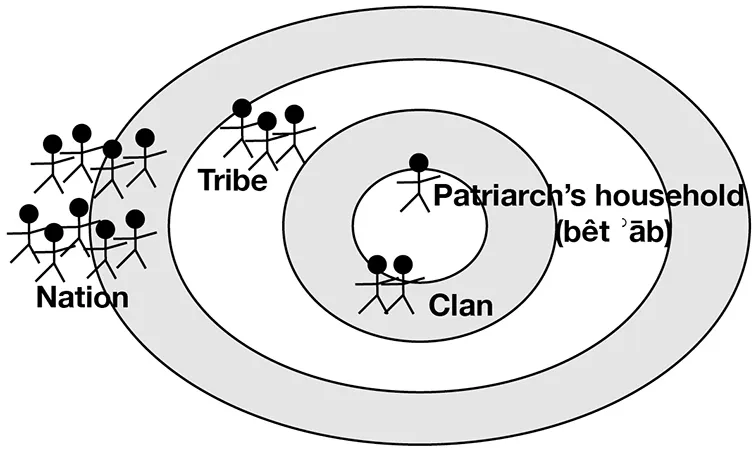

Figure 1.1. Israelite society

Patriarchal. The first of these terms, patriarchal, has to do with the centrality of the oldest living male member of the family to the structure of the larger society. In his classic work on the topic, Marshall Sahlins states that the societal structure of patriarchal tribalism involves a “progressively inclusive series of groups,” emanating from the patriarchal leader.5 In other words, the layers of society form in ever broader circles, radiating from the closely knit household to the nation as a whole as is pictured in figure 1.1. In Israel’s particular tribal system, an individual would identify their place within society through the lens of their patriarch’s household first, then their clan or lineage,6 then their tribe and finally the nation.7 Even the terminology for “family” in ancient Israel reflects the centrality of the patriarch. The basic household unit of Israelite society was known as the “father’s house(hold),” in Hebrew the bêt ʾāb. This household was what Westerners would call an “extended family,” including the patriarch, his wife(s), his unwed children and his married sons with their wives and children.

In this patriarchal society when a man married he remained in the household, but when a woman married she joined the bêt ʾāb of her new husband. An example of this is Rebecca’s marriage to Isaac in Genesis 24. She left her father’s household in Haran and journeyed to Canaan to marry.

Modern ethnographic studies indicate that the Israelite bêt ʾāb could include as many as three generations, up to thirty persons.8 Within this family unit, the “father’s house(hold)” lived together in a family compound, collectively farming the land they jointly owned and sharing in its produce.9 This extended family shared their resources and their fate.10 And those who found themselves without a bêt ʾāb (typically the orphan and the widow) also found themselves outside the society’s normal circle of provision and protection. This is why the Old Testament is replete with reminders to “care for the orphan and the widow.” So profound is Yahweh’s concern for those who stand outside the protection of the bêt ʾāb that he actually describes himself as “the God of gods and the Lord of lords, the great, the mighty, and the awesome God who does not show partiality nor take a bribe. He executes justice for the orphan and the widow, and shows His love for the alien by giving him food and clothing” (Deut 10:17-18). As we will see later in this chapter, there were numerous laws in Israelite society targeted at the protection of “the least of these”—the marginalized of Israel’s patriarchal society.

Correspondingly, it was the patriarch of the household who bore both legal and economic responsibility for the household. In extreme situations, he decided who lived and who died, who was sold into slavery and who was retained within the family unit. An example of this from the Bible is the story of Judah and Tamar in Genesis 38:6-26. Here Tamar has become a member of Judah’s bêt ʾāb by marriage, but is currently a widow. Although she is apparently no longer living under Judah’s roof (which is evidence that Judah is not fulfilling his responsibilities to her), she is still under his authority. When Tamar is found to be pregnant, the townspeople report her crime to Judah. It is obvious in this interaction that they expect him as the patriarch of her bêt ʾāb to administer justice.11 And so he does. Judah instructs the townspeople, “Bring her out and let her be burned!” (Gen 38:24). As the head of her household, Judah’s words carry the power of life and death for this young woman. We will return to this story a bit later in the chapter.

When the patriarch died, or when the bêt ʾāb became too large to sustain itself, the household would split into new households, each headed by the now-oldest living male family member. Consider the description of Abraham’s family in Genesis 11:26-32. Here Terah’s household consists of his adult sons, their wives and their children. His oldest son Haran “died in the presence of his father Terah” (perhaps while still a member of his household?) but Lot, Haran’s son, remains under Terah’s care. So when Terah migrates to the city of Haran, he takes Lot with him. When Terah dies, Abram, the eldest, becomes the head of the bêt ʾāb and therefore takes responsibility for his brother’s son. Thus Lot comes to Canaan with Abram.

Now Lot, who went with Abram, also had flocks and herds and tents. And the land could not sustain them while dwelling together; for their possessions were so great that they were not able to remain together. (Gen 13:5-6)

As a result, Abraham invites Lot to “be separated from upon me” (Gen 13:11). Lot chooses the fertile Jordan Valley and the original bêt ʾāb becomes two.12

Patrilineal. The term patrilineal has to do with tracing ancestral descent (and therefore tribal affiliation and inheritance) through the male line. In Israel the possessions of a particular lineage were carefully passed down through the generations, family by family, according to gender and birth order, in order to provide for the family members to come and to preserve “the name” of those gone before.

The genealogies of the Old Testament make this legal structure obvious—women are typically not named. When women are named, something unusual is afoot and we should be asking why. A woman might be named in a genealogy if a man had several wives who each had sons, as is the case with Jacob and Esau’s genealogies in Genesis 35 and Genesis 36. A woman ...