If you wereborn as long as fifty

years ago, you can remember a time when the test of a sound,

common-sense mind was refusing to fool with "new-fangled notions."

Without exactly putting it into a formula, people took it for

granted that truth was known and familiar, and anything that was

not known and familiar was nonsense. In my boyhood, the funniest

joke in the world was a "flying machine man"; and when my mother

took up a notion about "germs" getting into you and making you

sick, my father made it a theme for no endof domestic wit. Even as

late as twenty years ago, when I wanted to write a play based on

the idea that men might some day be able to make a human voice

audible to groups of people all over America, my friends assured me

that I could not interest the public in such a fantastic

notion.

Among the objects of scorn, in my

boyhood, was what we called "superstition"; and we made the term

include, not merely the notion that the number thirteen brought you

bad luck; not merely a belief in witches, ghosts and goblins, but

also a belief in any strange phenomena of the mind which we did not

understand. We knew about hypnotism, because we had seen stage

performances, and were in the midst of reading a naughty book

called "Trilby"; but such things as trance mediumship,automatic

writing, table-tapping, telekinesis, telepathy and

clairvoyance—we didn't know these long names, but if such

ideas were explained to us, we knew right away that it was "all

nonsense."

In my youth I had the experience of

meeting a scholarly Unitarian clergyman, the Rev. Minot J. Savage

of New York, who assured me quite seriously that he had seen and

talked with ghosts. He didn't convince me, but he sowed the seed of

curiosity in my mind, and I began reading books on psychic

research. From first to last, I have read hundreds of volumes;

always interested, and always uncertain—an uncomfortable

mental state. The evidence in support of telepathy came to seem to

me conclusive, yet it never quite became real to me. The

consequences of belief would be sotremendous, the changes it would

make in my view of the universe so revolutionary, that I didn't

believe, even when I said I did.

But for thirty years the subject

has been among the things I hoped to know about; and, as it

happened, fate was planning tofavor me. It sent me a wife who

became interested, and who not merely investigated telepathy, but

learned to practice it. For the past three years I have been

watching this work, day by day and night by night, in our home. So

at last I can say that I am nolonger guessing. Now I really. know.

I am going to tell you about it, and hope to convince you; but

regardless of what anybody can say, there will never again be a

doubt about it in my mind. I know!

Telepathy, or mind-reading: that is to say, can one human mind communicate with another human mind, except by the sense channels ordinarily known and used—seeing, hearing, feeling, tasting and touching? Can a thought or image in one mind be sent directly to another mind and there reproduced and recognized? If this can be done, how is it done? Is it some kind of vibration, going out from the brain, like radio broadcasting? Or is it some contact with a deeper level of mind, as bubbles on a stream have contactwith the water of the stream? And if this power exists, can it be developed and used? Is it something that manifests itself now and then, like a lightning flash, over which we have no control? Or can we make the energy and store it, and use it regularly,as we have learned to do with the lightning which Franklin brought from the clouds?

These are the questions; and the answers, as well as I can summarize them, are as follows: Telepathy is real; it does happen. Whatever may be the nature of the force, it has nothing to do with distance, for it works exactly as well over forty miles as over thirty feet. And while it may be spontaneous and may depend upon a special endowment, it can be cultivated and used deliberately, as any other object of study, in physicsand chemistry. The essential in this training is an art of mental concentration and autosuggestion, which can be learned. I am going to tell you not merely what you can do, but how you can do it, so that if you have patience and real interest, you can make your own contribution to knowledge.

Starting the subject, I am like the wandering book-agent or peddler who taps on your door and gets you to open it, and has to speak quickly and persuasively, putting his best goods foremost. Your prejudice is againstthis idea; and if you are one of my old-time readers, you are a little shocked to find me taking up a new and unexpected line of activity. You have come, after thirty years, to the position where you allow me to be one kind of "crank," but you won't standfor two kinds. So let me come straight to the point—open up my pack, pull out my choicest wares, and catch your attention with them if I can.

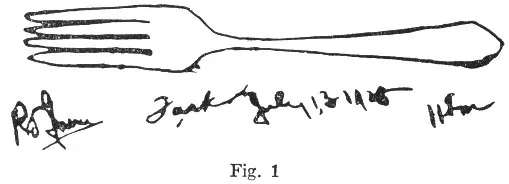

Here is a drawing of a table-fork. It was done with a lead-pencil on a sheet of ruled paper, which has beenphotographed, and then reproduced in the ordinary way. You note that it bears a signature and a date (fig. 1):

This drawing was produced by my brother-in-law, Robert L. Irwin, a young business man, and no kind of "crank," under the following circumstances. He was sitting in a room in his home in Pasadena at a specified hour, eleven-thirty in the morning of July 13, 1928, having agreed to make a drawing of any object he might select, at random, and then to sit gazing at it, concentrating his entire attention upon it for a period of from fifteen to twenty minutes.

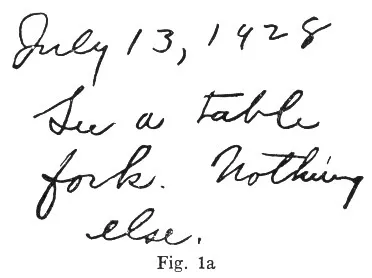

At the same agreed hour, eleven-thirty in the morning of July 13, 1928, my wife was lying on the couch in her study, in our home in Long Beach, forty miles away by the road. She was in semi-darkness, with her eyes closed; employing a system of mental concentration which she has been practicing off and on for several years, and mentally suggesting to her subconscious mind to bring her whatever was in the mind of her brother-in-law. Having become satisfied that the image which came to her mind was the correct one—because it persisted, and came back again and again—she sat up and took pencil and paper and wrote the date, and six words, as follows (fig. 1a):

A day or two later we drove to Pasadena, and then in the presence of Bob and his wife, the drawing and writing were produced and compared. I have in my possession affidavits from Bob, his wife, and my wife, to the effect that the drawing and writing were produced in this way. Later in this bookI shall present four other pairs of drawings, made in the same way, three of them equally successful.

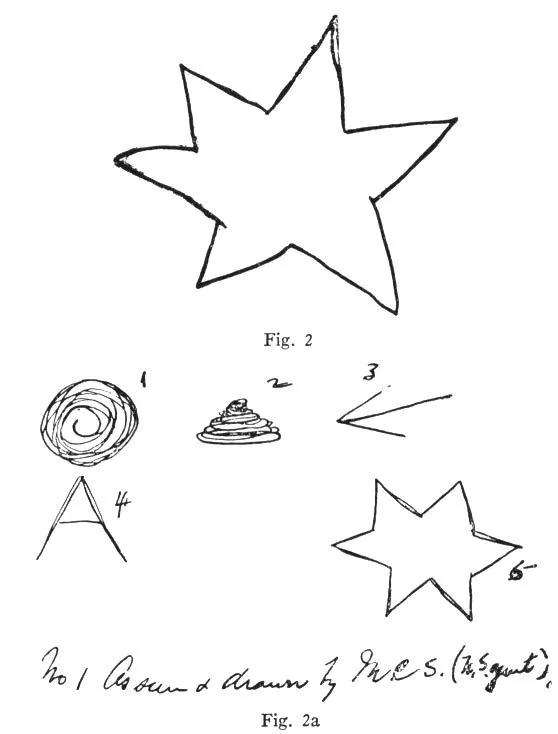

Second case. Here is a drawing (fig. 2), and below it a set of five drawings (fig. 2a):

The above drawings were produced under the following circumstances. The single drawing (fig. 2) was made by me in my study at my home. I was alone, and the door was closed before the drawing was made, and was not opened until the test was concluded. Having made the drawing, I held it before me and concentrated uponit for a period of five or ten minutes.

The five drawings (fig. 2a) were produced by my wife, who was lying on the couch in her study, some thirty feet away from me, with the door closed between us. The only words spoken were as follows: when I was readyto make my drawing, I called, "All right," and when she had completed her drawings, she called, "All right" —whereupon I opened the door and took my drawing to her and we compared them. I found that in addition to the five little pictures, she had writtensome explanation of how she came to draw them. This I shall quote and discuss later on. I shall also tell about six other pairs of drawings, produced in this same way.

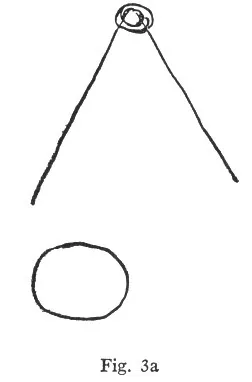

Third case: another drawing (fig. 3a), produced under the following circumstances. Mywife went upstairs, and shut the door which is at the top of the stairway. I went on tip-toe to a cupboard in a downstairs room and took from a shelf a red electric-light bulb—it having been agreed that I should select any small article, of which there were certainly many hundreds inour home. I wrapped this bulb in several thicknesses of newspaper, and put it, so wrapped, in a shoe-box, and wrapped the shoe-box in a whole newspaper, and tied it tightly with a string. I then called my wife and she came downstairs, and lay on her couch and put the box on her body, over the solar plexus. I sat watching, and never took my eyes from her, nor did I speak a word during the test. Finally she sat up, and made her drawing, with the written comment, and handed it to me. Every word of the comment, as well as the drawing, was produced before I said a word, and the drawing and writing as here reproduced have not been touched or altered in any way (fig. 3a):

The text of my wife's written comment is as follows:

"Firstsee round glass. Guess nose glasses? No. Then comes V shape again with a 'button' in top. Button stands out from object. This round top is of different color from lower part. It is light color, the other part is dark."

To avoid any possible misunderstanding, perhaps I should state that the question and answer in the above were my wife's description of her own mental process, and do not represent a question asked of me. She did not "guess" aloud, nor did either of us speak a single word during this test, except the single word, "Ready," to call my wife downstairs.

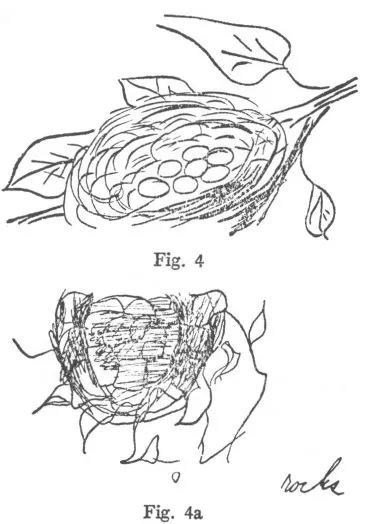

The next drawings were produced in the following manner. The one at the top (fig. 4) was drawn by me alone in my study, and was one of nine, all made at the same time, and with no restriction uponwhat I should draw—anything that came into my head. Having made the ninedrawings, I wrapped each one in a separate sheet of green paper, to make it absolutely invisible, and put each one in a plain envelope and sealed it, and then took the nine sealed envelopes and laid them on the table by my wife's couch. My wife then took one of them and placed it over her solar plexus, and lay in her state of concentration, while I sat watching her, at her insistence, in order to make the evidence more convincing. Having received what she considered a convincing telepathic "message," or image of the contents of the envelope, she sat up and made her sketch (fig. 4a) on a pad of paper.

The essence of our procedure is this: that never did she see my drawing until herswas completed and her descriptive words written; that I spoke no word and made no comment until after this was done; and that the drawings presented here are in every case exactly what I drew, and the corresponding drawing is exactly what my wife drew, with no change or addition whatsoever. In the case of this particular pair, my wife wrote: "Inside of rock well with vines climbing on outside." Such was her guess as to the drawing, which I had meant for a bird's nest surrounded by leaves;...