- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

Reggio Emilia's educational services for 0-6 year olds are widely acclaimed as one of the best systems in the world.

Now in an updated second edition, In Dialogue with Reggio Emilia offers a collection of the most important articles, lectures and interviews given by Carlina Rinaldi, who was President of Reggio Children for a decade, and pedagogical director of the Reggio Emilia Infant-toddler Centres and Preschools after working closely with Loris Malaguzzi, Reggio Children founder and inspirer of the Reggio Emilia Approach. She is currently President of Fondazione Reggio Children – Centro Loris Malaguzzi.

With a full introduction contextualising each piece of work, it offers a unique insight into many of the themes that characterise the early childhood curriculum of Reggio Emilia: participation, documentation and assessment; professional development; organisation; research; creativity; spaces and environments in education, and more. This second edition includes brand new chapters exploring the role of the Loris Malaguzzi International Centre; the natural complexity of becoming children; Rinaldi's speech on receiving the LEGO prize; and Jerome Bruner's friendship with the schools of Reggio Emilia and the author.

A deeply personal book, this is an invaluable resource for practising teachers, students and researchers. It is essential reading for anybody looking to further their understanding of the Reggio Emilia philosophy and pedagogical practice.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

PART I

Carlina Rinaldi:

Writings, speeches and interviews, 1984–2004

1

Staying by the children’s side

The knowledge of educators (1984)

Forging the educational project in the community

- This is the century in which the quality of the parent–children relationship has emerged for the first time as a theoretical proposition (though tampered with, in practice), and as a public topic and issue, i.e. of a social and cultural nature. More particularly, it is the first time that a public education institution (i.e. the nido) has sought the active, direct and explicit participation of parents in the formulation of the educational project. [Added by CR when editing the 1st edition of the book: usually parents are expected to delegate responsibility to the teachers and rarely discuss choices which have been made for fear their children may be made to pay for questioning teachers’ decisions. For us, this was to be avoided at all costs.]

- Therefore, over and above the frequent accusations of its limitations and ambiguities which do require urgent change, law 1044 represents a very advanced step even today, at least as far as participation and social management are concerned. It is advanced because it sanctions a public institution for the healthy child (not only the handicapped [Editors’ Note: the piece was written in 1984 and this was the usual term in those years for disabled] or sick child), and because of the definition and recognition it gives to the municipality as the managing body of socio-educational institutions. But most of all, it is advanced because it underlines the centrality of the nido not only in the relationship between educator and child but also in the interaction between family environment and nido environment. It does so not through illusory simplifications of theories of educational continuity, but by highlighting instead the dialogic nature and permanent dialectic quality of the relationship. [Added by CR when editing the 1st edition of the book: here I am underlining, for the nido, the centrality placed not only on the relationship between child and teacher but on the relationship between the child, teachers and parents. The meaning of the nido lies in the interaction between these subjects, in encouraging these relationships. The nido is a place of relationships and communication, a place where a way or culture of teaching is constructed.]

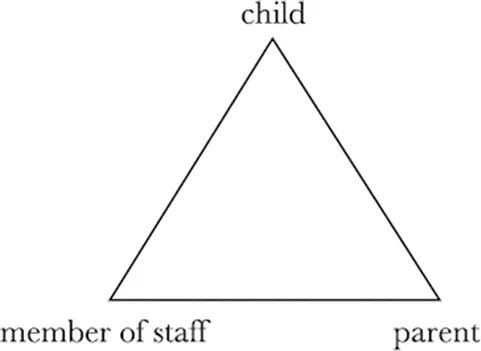

- The nido is therefore a communication system that is integrated in the wider social system: a system of communication, of socialisation, of personalisation [Added by CR when editing the 1st edition of the book: I mean valuing the subjectivity of each person, child and adult], of interactions in which there are three main interested subjects affected by the educational project, i.e. the child, the educator and the family. These three subjects are inseparable and integrated; in order to fulfil its main task, the nido needs to be concerned and deal with the well-being of staff and of parents as well as with that of the children. The system of relations is so integrated that the well-being or malaise of one of the three protagonists is not only correlated but interdependent with that of the other two.

- This well-being is closely associated with the quantity and quality of: (a) the communication that takes place between the parties, (b) the knowledge and awareness which the parties have of their mutual needs and satisfaction, and (c) the opportunities for meeting and getting together which arise in a system of permanent relations.

- The identity of the nido therefore hinges on this system of relations-communications in which the active participation of the parents (both social participation and management) is considered an integral part of the educational experience.

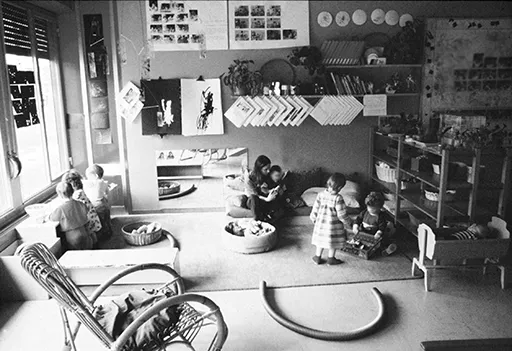

Figure 1.1 Arcobaleno municipal Infant-toddler Centre (Nido), Reggio Emilia, 1979

Figure 1.1 Arcobaleno municipal Infant-toddler Centre (Nido), Reggio Emilia, 1979 - As we have often stated, if all this is to go beyond the purely conceptual and abstract, there needs to be a strong commitment at the organisational level – which is itself subject to constant appraisal and adjustment – and at the functional, methodological and political level. Everything else develops automatically from this, e.g. the architecture of the nido (the spaces and furniture), the methods and timeframes of communication, the working hours of the staff, the concept of collegiality and educational freedom, and the meaning and contents of professional development. From exchange and dialogue with families, new concepts emerge which define the very idea of participation and of the nido. [Added by CR when editing the 1st edition of book: a participatory nido is a school where one learns to listen, where the competencies of each person (child and adult) can be expressed and find appreciation, where progettazione is preferred to programmazione [see discussion of these terms on page xii], where the concept of democracy is not based on who has the majority but on the construction of consent, of agreed meaning, of mutual consent.]

Figure 1.2

Figure 1.2 - Finally, it seems to have been accepted that these processes of relations-communication, particularly between staffs–parents–local community, need organisation, conceived and implemented with the same flexibility as well as with the same skill and commitment required by the kinds of relations-communications and interactions we have with the children.

- a distinguishing feature of the historical moment in which we are living is change, movement and becoming. In Italy this has given rise to a large-scale and profound transformation of an economic and technological–social–institutional–moral nature and with a political dimension. This, in turn, has produced numerous and sometimes dramatic problems, the management of which has turned the attention of political forces away from the problems of education in general and of school in particular (where reforms have never been completed). As a whole, schools in Italy are seriously behind in comparison to other countries in responding to changes and new requirements and are undergoing a painstaking process in their search for a new role and a new identity;

- the policy of the welfare state has been massively attacked on many occasions in words and deeds (economic), as has, on the whole, the policy of decentralisation and participation, with criticisms that are sometimes well founded but also with prejudiced criticisms. This has caused a reaffirmation of the centrality of power and a rejection of every form of decentralisation. In practice this has led to a serious weakening of services both at the economic level and at the cultural, social and political level;

- all those many organisations which talk of participation, but do not make it possible for the real actors to act and decide by taking on responsibility, are going through a period of crisis. At times, there has been too much emphasis on participation but without a sufficient focus on its contents and on the participation processes, whose key players have not been properly analysed and have often been sacrificed between the quest for consensus and centralising trends.

The family and the social context

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Note on terminologies

- Introduction to the First Edition (2006): Our Reggio Emilia Dahlberg and Peter Moss

- PART I CONTENTS OF THE FIRST EDITION: Carlina Rinaldi: Writings, speeches and interviews, 1984–2004

- PART II CONTENTS OF THE SECOND EDITION: Carlina Rinaldi: Writings and speeches 2007–2016

- Bibliography

- Index