![]()

1

Women and Criminality: Counting and Explaining

Across the modern period commentators have argued that women as a sex are less likely than men to engage in criminal activity. Yet they have disagreed on the reasons. For the psychologist Havelock Ellis, writing in 1894, there was ‘scarcely [. . .] any doubt that the criminal and anti-social impulse is less strong in women than in men’.1 In his published memoirs of 1931, high-profile London detective Frederick Porter Wensley explained women’s lower levels of participation in terms of social roles rather than instinct: ‘women [. . .] may be just as wicked as men, but their opportunities for crime on a big scale are more restricted’.2 The collation of criminal justice statistics from the early nineteenth century onwards exposed apparently lower levels of female participation in criminality. Women formed 17 per cent of the prison population in England and Wales in the nineteenth century; this was reduced further to 4 per cent by the 1980s although figures are now rising starkly.3 Criminality as a concept came to be defined in terms of masculinity. The scientific study of offending behaviour – which has come to be labelled ‘criminology’ – can be dated back to the analytical work carried out by prison medical officers from the 1860s onwards. These studies focused overwhelmingly on male prisoners and thus the set of characteristics associated with male offenders was viewed as a ‘norm’ or ‘type’ against which deviancy was measured.4 Women’s offending has tended to be viewed not merely as unusual, but in extreme cases (including press representations of Myra Hindley or Rosemary West) as ‘doubly deviant’ in that it contradicts gendered assumptions about ‘caring’ femininity as well as threatening broader social norms through the act of law-breaking.5 Indeed, the assumption that certain types of criminal women are exceptionally ‘monstrous’ can be linked to the dualistic depiction of women as infinitely good or infinitely evil within Judeo-Christian frameworks. This did not mean that all women implicated in offending were treated harshly; indeed, far from it. Rather, notable exceptions to norms of ‘womanhood’ have been held up as cultural icons of feminine ‘evil’.

This chapter will assess whether and to what extent historians have replicated the assumptions that underpinned early criminological investigation in either ignoring women’s offending behaviour or assuming low levels of activity. It will begin by assessing the historical incidence of women’s involvement in criminal activity, focusing on the difficulties of quantitative analysis, including the problematic nature of data sources. To what extent have women always been prosecuted in far smaller numbers than men? Did they gradually ‘vanish’ from the criminal justice system and, if so, why? Were women treated with greater or less leniency than men when they encountered the mechanisms of criminal justice? Finally the chapter will assess women’s involvement in court procedure as witnesses, prosecutors and complainants. It will suggest ultimately that the trends that are evidenced in criminal justice statistics must be viewed as an important point of intersection between the processes of criminal justice and the behaviours of those accused, but that they must be evaluated carefully and critically. Ultimately, any study of women and crime needs to engage with the broad range of regulatory practices through which femininity has been situated and experienced in the modern period. A focus that is limited to criminal justice itself gives only a blinkered view.

The case of the vanishing female

Historians attempting quantitative analysis of the gendering of offending behaviour are dependent on the survival and accuracy of data generated by the criminal justice system itself. National profiles of the business of the courts are not available for the years before 1805, whilst the classification of offences that is used today was introduced in 1834. With the expansion of the bureaucratic state and the development of the statistical movement in the nineteenth century, criminal justice and law enforcement agencies were required to submit annual figures to central government; even so, methods of recording the gendering of offences has varied. For earlier periods, the business of the Assize and Quarter Sessions (higher courts) can only be reconstructed through painstaking examination of individual indictments (formal written accusations, often on parchment, that were prepared as a defendant was committed by a magistrate to stand trial). Moreover, the survival of indictments may be sporadic so that samples need to be constructed of years for which there is a clear run. Such work was pioneered by J. M. Beattie for the counties of Sussex and Surrey between 1663 and 1802.6 It has been joined by a range of studies including those by Garthine Walker (on Cheshire 1590–1670), Gwenda Morgan and Peter Rushton (on the north-east 1714–1800), and Peter King on Essex and London (1740–1820).7 The business of magistrates or Justices of the Peace (the lowest but very important first rung of criminal function) is only just beginning to receive attention.8

Historians of the Early Modern period have often concentrated their attention on the work of the Old Bailey, which acted as an Assize court for London. This is because detailed accounts of the Old Bailey’s proceedings (recorded in short-hand by reporters) were published for popular consumption from 1674 until 1913, providing a rich seam of data for historians to mine. Moreover, these sources have recently been digitised (as the Old Bailey Proceedings Online), providing a fully searchable and publicly available database of criminal justice cases.9 The full potential of such an electronic resource is only just being realised and it is likely to generate both extensive and highly innovative studies not merely of criminality but of the daily lives of Londoners. However, the sheer richness of the Old Bailey material can lead to a research bias in favour of urban and, more specifically, the metropolitan experience. Findings for the London courts need to be set alongside continued work on other regions and locales.

Criminal justice historians are inclined to agree that English women tended to be prosecuted for far fewer offences involving violence than men (in contrast to Scotland where, as the work of Anne-Marie Kilday has shown, women were charged with over a third of all offences against the person).10 Women in England were most likely to appear before the courts in urban areas for theft, drunkenness (or public order offences) and prostitution-related offences (soliciting charges tended to be applied exclusively to women). Historians also agree that English women were more likely than men to be given lesser sentences once convicted. Finally and perhaps most significantly, they agree that women have tended to be prosecuted in fewer numbers than men in England (as elsewhere in Europe). There is considerable debate, however, as to whether a clear decline in the prosecution of women has taken place and, if so, when, where exactly, and why this occurred. In 1991 Malcolm Feeley and Deborah Little published an article, based on Old Bailey data, in which they argued that female offenders had gradually ‘vanished’ from the criminal justice process across the last three centuries. Using samples taken at 20-year intervals (1735, 1755, 1775, etc), they argued that women’s involvement as defendants had fallen from 45 per cent of all those committed for trial in 1735 to a mere 10 per cent in 1895. This, they suggested, was evidence that the marginalisation of women’s criminality was a relatively recent phenomenon and that it could be linked to changes in social attitudes and gendered behaviours.11

The ‘vanishing female’ thesis can be criticised from a number of perspectives. Firstly, findings drawn from Old Bailey data cannot be used to provide meaningful conclusions about England as a whole for the eighteenth century. London itself can be viewed as atypical precisely because of the intense urban experience that it offered; young women might move to the capital for work, away from established networks and supports, leading to a period of economic vulnerability. Peter King’s extensive research on Assizes and Quarter Sessions in Essex has shown no obvious decline in the prosecution of women across the eighteenth century in what was a predominantly rural county. Rather, females formed around 13 per cent of those indicted for property offences across the period 1740–1804.12 The work of J. M. Beattie also shows, like King, that the metropolitan urban experience needs to be distinguished from the rural experience. In rural parishes of Surrey and Sussex, women constituted only 11 per cent of those charged with offences against the person for samples obtained between 1663 and 1802; for offences against property, women constituted 14 per cent of those charged in rural Surrey and 13 per cent of those charged in rural Sussex. Urban areas of Surrey demonstrated higher levels of charges against women (22 per cent of those charged with offences against the person and 28 per cent of those charged with property offences).13 These are not, however, out of kilter with trends for the Old Bailey in the 1790s which King has shown to average around 25 per cent.14 Ultimately, as King has argued, patterns for the eighteenth century are not distinctly different from that of the late twentieth century in which women have also formed a small minority of those accused (12 per cent of females prosecuted for indictable offences in England and Wales in 1960 – see Table 1.1). A further problem with the method used by Feeley and Little is the use of 20-year intervals for samples. The years selected are not necessarily representative, whilst the impact of war, which removed a sizeable proportion of young male labourers from London’s population, is not accounted for.15

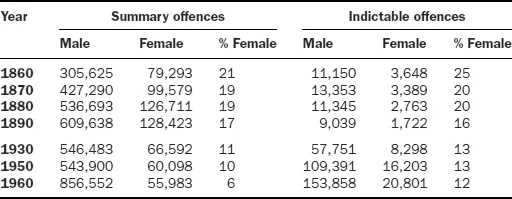

Table 1.1 Persons proceeded against, England and Wales, by sex

Source: Criminal Statistics, England and Wales (Police Returns), British Parliamentary Papers (BPP).

(Note: Comparable data is not available for the period of the Second World War.)

In relation to the eighteenth century, then, a complexity argument emerges, in which patterns can be seen as regionally distinct, linked to the specific demographic and economic characteristics of parishes, towns and cities. Morgan and Rushton have found that women constituted a half of all thieves prosecuted in Newcastle in the mid-eighteenth century, which they link to women’s high demographic representation (57 per cent of the population of Newcastle was female in 1801). London and Newcastle emerge as ‘atypical’ compared to patterns elsewhere. In many rural areas, women were never prosecuted in high proportions. If there was a ‘decline’, it is unlikely that the eighteenth century is the period in which this began.

Can the ‘vanishing woman’ thesis be more accurately sustained for the nineteenth century? As Table 1.1 demonstrates, if we study more serious ‘indictable’ offences (which could only be tried in the higher courts), women were gradually disappearing from view. Yet we also need to account for the growing role of magistrates (summary justice) and their ability to hear cases previously only dealt with by Assizes and Quarter Sessions. The Criminal Justice Act of 1855 was particularly important in this regard. Along with other legislation it enabled magistrates to hear cases of theft that had, previously, constituted a large proportion of higher court business. Similarly, magistrates were also empowered to try common assault cases. Sue Grace’s study of York has shown that women formed 18 per cent of all summary convictions in 1849 but that this rose to 34 per cent in 1860.16 Thus the contours of criminal justice were themselves changing. Table 1.1 certainly indicates that the percentage of proceedings for indictable offences against females had fallen to 16.0 per cent by 1890 (from 24.7 per cent in 1860). Yet this requires qualification, since females were still appearing for summary offences (before magistrates) in large numbers. Indeed, there was an increase in female appearances for summary offences of around 50,000 (a rise in number of 62 per cent): from 79,293 to 128,423. Prosecution rates for males were simply rising even more steeply. This is one piece of evidence which suggests that the ‘vanishing woman’ thesis might be more appropriately replaced by a thesis regarding the growing ‘criminalisation of men’ in the Victorian period.17

National aggregates of course conceal local patterns of variation which might be linked to conditions and standards of living. In London’s East End, for example, women appeared more regularly as defendants in the police court in the late nineteenth century. A sample of the 2174 cases coming before Thames Police Court between July and September 1888 shows that 27 per cent of all defendants were female.18 This figure was particularly affected by their prosecution for drink-related public order offences: women formed 46 per cent of those charged in the East End compared to a presence of just over a third in national profiles of summary offences. Clearly alcohol was a coping mechanism as well as an exacerbating factor in lives structured by real poverty, insecurity and overcrowding. Moreover, the overtly ‘public’ worlds of the East End’s destitute women, who inhabited the streets, sleeping rough or making use of lodging houses, brought them under closer police scrutiny. Beneath the national profiles a dense set of local scenarios require unravelling in order to explain why aggregates appear the way that they do.

Women’s declining presence in court (in terms of both numbers and relativity to male prosecutions) is a phenomenon of the first half of the twentieth century (see Table 1.1). In relation to summary offences, this decline between 1890 and 1930 can in part be accounted for by a drop in prosecutions for soliciting, which were proving increasingly troublesome to convict, thus showing that strategies of policing, as much as women’s actual behaviours, have shaped court profiles. The numerical increase in summary offences by 1960 is wholly accounted for by the growth in motoring offences (linked to car ownership) and for which men were prosecuted in far larger numbers than women.19 It is worth noting, however, that proceedings for common assault have continued to be taken against females in significant proportions, forming consistently a third of all such cases coming before magistrates in our three sample years of 1930, 1950 and 1960. At the beginning of the twenty-first century adult women constitute around 16 per cent of those arrested by the police for offences.20 Thus, once again, a simple narrative of increased decline across time appears insufficient.

Explaining women’s absence

It is clear, however, that women have appeared in the courtroom in significantly smaller numbers than men, although there have been exceptions to this rule. Reasons for this have been hotly debated. Socio-biologists have tended to emphasise essential hormonal, physical and psychological differences between men and women (what Ellis called ‘impulse’), which have made women less likely to display aggression across cultures and societies.21 In contrast, feminist historians have turned their attentions to stark continuities within social and cultural formations. They suggest that women’s association with the household and with domesticity has restri...