![]()

Part One

The Me-Centered Self

![]()

1

How the Me-Centered World Was Born

As children we never questioned our identity or wondered about our place in life. Nor did we think of our “selves” as distinct from our relationships, activities and feelings. We just lived in the context we were born into and followed the natural course of our lives. But as we grew older we were encouraged to discover our own unique blend of preferences, talents and joys, and to create an identity for ourselves through our choices and actions. In contrast to previous ages, modern culture denies that one can become an authentic person or experience fulfillment in life by conforming to natural or socially given relationships and roles. Instead we are taught that our self-worth and happiness depend on reconstructing ourselves according to our desires. And the project of redesigning ourselves necessitates that we continually break free from the web of social relationships and expectations that would otherwise impose an alien identity on us.[1] I am calling this understanding of the self “me-centered,” not because it is especially selfish or narcissistic but because it attempts to create its identity by sheer will power and rejects identity-conferring relationships unless they are artifacts of its own free will. It should not surprise us, then, to find that the modern person feels a weight of oppression and a flood of resentment when confronted with the demands of traditional morality and religion. In the face of these demands the me-centered self feels its dignity slighted, its freedom threatened and its happiness diminished.

In this chapter I draw heavily on the work of moral philosophers Charles Taylor and Alasdair MacIntyre to answer the following question: How, when and by whom did it come about that nature, family, community, moral law and religion were changed in the Western mind from identity-giving, happiness-producing networks of meaning into their opposites—self-alienating, misery-inducing webs of oppression?[2] How was the me-centered world formed?

Searching for Identity in a Secular Age

In his Sources of the Self (1989) and The Secular Age (2007), Charles Taylor argues that to possess an identity is to be located in a moral “space” whose coordinates are determined by certain goods and moral sources. The question Who am I? is answered by “knowing where I stand” in relation to these goods and moral sources.[3] As Taylor explains, “To know who you are is to be oriented in moral space, a space in which questions arise about what is good or bad, what is worth doing and what not, what has meaning and importance for you and what is trivial and secondary.”[4] Oriented within this space I can know what I ought to do, what is valuable, worthwhile and admirable. Modern moral space possesses three axes that provide coordinates (x, y, z) within which to locate ourselves. Each axis represents a set of “strongly valued goods.”[5] That is, these “ends or goods stand independent of our own desires, inclinations, or choices, that they represent standards by which these desires and choices are judged.”[6]

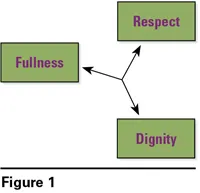

They are (x) a sense of respect for and obligation to others, (y) a sense of fullness in life or what makes life worth living, and (z) a sense of our own dignity or what makes us worthy of respect (see fig. 1).

The shape of modern identity can be determined by coming to understand the way contemporary culture appropriates these fundamental values in contrast to the way premodern culture understood them. To give us historical perspective, Taylor traces in three trajectories how these strong values acquired their modern shape. He shows how (1) the growth of inwardness transferred moral principles from outside the human person to inside, (2) the Christian affirmation of ordinary life gradually led Western culture to focus on human flourishing in this world as the exclusive human goal, and (3) the development of an expressive view of inner nature produced a completely subjective view of the good. Taylor’s three historical motifs provide the following outline. We will see how each of these trajectories adds to our understanding of the modern self’s take on the strong values of respect, fullness and dignity.

The development of inwardness. In contrast to modern inwardness, ancient tribal and warrior cultures people found their identity in a moral space where respect, fullness and dignity were grounded in external things such as family status or war and the glory it achieves. Taking a first step toward inwardness, Plato (c. 428/27-347/48 b.c.) criticized the warrior morality, arguing that desire for glory and other unruly emotions must be subordinated to reason.[7] Reason’s power of self-control centers the self and bestows the capacity for cool, deliberate action. But Plato does not locate all goods and moral sources within the self. For Plato, to reason is to see the natural order of the world and perceive the transcendent good to which it is directed. And one becomes a good human being by imitating the good thus revealed.

The Christian thinker Augustine of Hippo (a.d. 354-430) takes Plato’s thinking further toward inwardness. When we turn our thoughts inward to consider our minds, we discover a vast mystery. The mind contains an endless universe of ideas and memories; it can even think about itself. Yet the mind cannot comprehend itself, explain its own powers or create the ideas it contains. Hence, Augustine concludes that our minds must be created and illuminated by an even greater mystery, a divine mind.[8] So Augustine finds humanity’s greatest good revealed not in the natural order but in the divine truth seen by introspection. In contrast to Plato, Augustine denies that one can see the good just by turning to the natural order. We must also possess purity of heart, which only the grace of God can bestow. Here Augustine introduces a new function of the will, derived from Christianity, into Western thought. Right reason cannot function properly in a person who desires evil. We must will the transcendent good before we can see it clearly. Hence, the will must be liberated from evil desires before the mind can endure the truth. Even though Augustine’s inward turn was revolutionary, he did not yet identify the human soul with the good and the true. The soul is merely the place where one can perceive the truth that transcends even the soul. Thinkers after Augustine followed his example in looking for the true good within the soul.

René Descartes and disengaged reason. The next step toward placing moral values wholly inside the self was facilitated by a revolution in natural science.[9] Galileo (1564-1642) is famous for using a telescope to spot Jupiter’s moons; however, more enduring was his revolution of changing the metaphor for interpreting the physical world. Before Galileo, philosophers thought of the physical world as a combination of matter and form or idea. The world was a sort of living body, composed of matter and soul. In contrast, Galileo saw the world as a machine, as dead matter arranged by God in a certain order. The body of the world no longer possesses a soul. The French philosopher René Descartes (1596-1650) accepted Galileo’s view that the world is a material machine bereft of soul. But he did not want to accept atheism or reduce everything to matter; hence, to preserve the existence of nonmaterial forms and purposes Descartes relocated them within the mind. The human mind does not get its ideas from the external cosmic order. Instead, it imposes its internal order on the external world like God does. Notice the difference between Descartes and Plato. In Plato, the human mind humbly allows itself to be shaped by the natural order. For Descartes, mind—whether divine or human—asserts its superiority over the external world by imposing itself on it.[10]

Shifting from a passive to an active understanding of the mind’s relationship to the world leads inexorably to a shift in human self-understanding and moral theory. For Descartes, our bodies are machines just like the rest of the world, so we can direct them and their emotions with reason in the same way we control the external world. The emergence of this dominating attitude toward the world and human nature indicates a profound change in Descartes’s understanding of freedom. For Plato and the Platonic tradition, freedom can be attained only by bringing one’s life into harmony with the ideal order that gives form and being to the world. For Descartes, freedom is the natural power to rule oneself as one chooses:

Now freewill is in itself the noblest thing we can have because it makes us in a certain manner equal to God and exempts us from being his subjects; and so its rightful use is the greatest of all goods we possess, and further there is nothing that is more our own or that matters more to us. From all this it follows that nothing but freewill can produce our greatest contentment.[11]

In this framework, moral sources have been completely internalized within the mind. Our understanding of what is good and our power to attain it now must come from within, from “the agent’s sense of his own dignity as a rational being.”[12]

John Locke and the punctual self. John Locke (1632-1704) differed profoundly from Descartes in many ways, but he continued the path tread by Descartes toward disengaging the self from the matrix of nature. Locke was radically antiteleological, that is, he believed that there are no inherent ends (teloi) toward which the world or human nature strives. Human nature does not possess “an inherent bent to the truth or to the good.”[13] This rejection of teleology works a revolution in ethics. We cannot think of human nature as made for truth or love or any virtue. According to Locke, human nature inherently seeks only pleasure and avoids only pain. There is no inherent connection between essential human nature and moral good or evil that would guarantee that good always produces happiness and evil unhappiness. This connection must be established arbitrarily and extrinsically, by God or habit or tradition.[14] If we choose, we can disengage from this habitual connection and remake ourselves in any way we choose. Aristotle (384-322 b.c.) noted that a habit can be formed with or against the grain of nature. For Locke, however, there is no grain of nature, and a habit is a mere association of atoms of experience. As Taylor explains, “Habits now link elements between which there are no more relations of natural fit. The proper connections are determined purely instrumentally, by what will bring the best results, pleasure, or happiness.”[15] For Locke, the self has no identifying attributes or relations or unchangeable structures. It is just an extensionless point, which Taylor calls the “punctual self.”[16] On this reading, the modern self sits sovereign above the world, impressing its arbitrary will on a neutral external reality and reconstructing itself according to its whims.

The moral space of inwardness. Where does the history of internalization of moral sources locate modern identity on the three axes of moral space (see. fig. 1)? First, on the x axis of respect, if internalization and rational self-control mark the being of others we will see other people as individual autonomous agents and feel a special respect for their right to control their own lives. On the y axis of fullness, we will assume that fullness in life consists in ordering one’s passions according to reason and imposing one’s will on the external world. Perhaps living in this way brings about a sense of satisfaction at being in control of oneself and in exerting of power over nature. And on the z axis of dignity, one will find one’s dignity in the inner integrity of one’s being and in the power of self-control over passion and error. For the modern self, then, the most powerful reasons to respect others, the surest path to fullness and the clearest basis on which to assert our own dignity are internal to ourselves and others.

Affirmation of ordinary life. In traditional societies certain ways of living possess higher dignity than others do. In ancient warrior cultures a life of military glory and honor was to be sought above all others. But Plato criticized ambition for glory and advocated devoting oneself to wisdom. In his Politics Aristotle admits the necessity of living on the level of ordinary life, which Taylor calls the life of “production and reproduction.”[17] But ordinary life is merely a foundation from which one can aspire to the truly good life. For Aristotle, one should seek excellence in contemplating the natural order and in deliberating with others about the common good of the political community one can achieve the good life in. The Stoic philosophers pronounced an even more negative judgment on ordinary life, urging that wisdom dictates that one detach oneself from the fluctuating passions of the body so one can devote oneself to the unchanging order of reason.

Christianity affirms the goodness of creation and ordinary life, but it also holds dear the ideal of a life dedicated totally to God. The monastic movements of the early centuries, though not denying that ordinary life was good and could be acceptable to God, sought a higher spiritual plane by sacrificing marriage, family, society and commerce. Accordingly, medieval Christianity developed a hierarchical theory of the Christian life. Some are called out of ordinary life into monastic orders and the priesthood. These Christians devote themselves to prayer and study, and they refrain from marriage. They aim to achieve a higher level of holiness and merit before God, which can benefit the whole community. This system can lead to the idea that the laity need not concern itself with holiness and piety...