![]()

1

Worldviews over Coffee at Starbucks

WHEN CHRISTIANS SEE A BOOK about worldviews, they automatically assume it is about apologetics—a defense of the Christian faith. That assumption is correct for this book as well, but this is apologetics with an important twist. Like other worldview books, we attempt to demonstrate the inadequacies of non-Christian thought systems or life orientations, and to convince readers that Christianity offers something better. But that is not our only goal, and perhaps it is not even our primary purpose. The twist is that this apologetics book also aims to provoke Christians to adopt a Christian worldview. Too often, we assume that non-Christian worldviews stay safely on the other side of the church door. As you will see below, we believe that this is far from the case. In fact, much of this book grows out of our own self-reflection to isolate areas where hidden worldviews, alien to Christianity, have crept into our thoughts and lifestyles.

The theory that Christians are largely immune to the influence of non-Christian thought structures is often unconsciously perpetuated by worldview books that identify atheistic existentialism, postmodern deconstructionism, Marxism or similar philosophical systems as Christianity’s main competitors. These worldviews are, to be sure, contrary to a Christian view of the world in fundamental ways, and it is completely proper to frame an intellectual response to them. However, stopping here has two important limitations. First, somewhere along the line, Christians have bought into the idea that philosophies born and perpetuated in universities represent the greatest challenge to a Christian worldview. We believe that is wrong-headed. How many people do you know who are locked in deep conflict over whether to become an atheistic existentialist or a Christian? How many committed Marxists do you run into on a daily basis? The reality is that we don’t really encounter massive herds of people enticed by the thought systems found in a typical worldview book.

The second limitation of most worldview books is that they let Christian readers off the hook too easily. After reading such books, they frequently will conclude that the author is correct about the deficiencies of competing ideas and the sufficiency of Christian ideas. Because of this agreement, Christians often further conclude that their faith remains untainted by contrary worldviews. This creates a dangerous situation if the real competition for the hearts and minds of Christians and non-Christians alike does not spring from the academy, where the worldviews are clearly formulated and expressed. What if the real competition comes from worldviews we do not see at all, even if they surround us?

We believe this is the situation. It is not the worldviews that begin as theories or intellectual systems that mold the lives and beliefs of most people. Instead, the most powerful influences come from worldviews that emerge from culture. They are all around us, but are so deeply embedded in culture that we don’t see them. In other words, these worldviews are hidden in plain sight. We will occasionally call them “lived worldviews” because we are more likely to absorb them through cultural contact than adopt them through a rational evaluation of competing theories. These lived worldviews are popular philosophies of life that have few intellectual proponents but vast numbers of practitioners.

The eight belief systems we identify as hidden worldviews—individualism, consumerism, nationalism, moral relativism, naturalism, the New Age, postmodern tribalism and salvation by therapy—fit this model. This is certainly not an exhaustive list,[1] but they are among the most pervasive life-shaping perspectives in North American culture. If you observe carefully, you hear and see them everywhere—in offices, dormitories, Internet chat rooms and over-coffee-at-Starbucks conversations. Moreover, they are not limited to secular venues. Because of their stealthy nature, these worldviews find their way behind the church doors, mixed in with Christian ideas and sometimes identified as Christian positions.

This accounts for the “apologetic twist” mentioned at the beginning of the book. Many Christians have imported chunks of these worldviews without being aware of it. This is difficult to avoid because they are embedded throughout North American culture. Moreover, because we do not encounter them as intellectual systems, they usually fly under the radar of conscious thought. Thus, their power over us is increased since we are often unaware of how they shape our life and ideas. In short, no one is immune from the influence of these perspectives. They are very real competitors with Christianity, and they stake their claim on the lives of Christians and nonbelievers alike.

Because we will examine worldviews that are absorbed through culture rather than adopted through rational appraisal, the structure and approach of this book will differ from many others in the “worldview” category. Most worldview books proceed by investigating the writings of those who propose intellectual thought systems, and then they undertake a thorough evaluation of the coherence of these ideas. This makes perfect sense when examining worldviews that originate as theoretical systems. However, the over-coffee-at-Starbucks worldviews we examine do not have this sort of starting point. They may indeed have philosophical and academic connections or origins, but by the time these ideas trickle down to popular American culture, they manifest themselves in different ways. For example, what we call postmodern tribalism has roots in postmodern philosophy, as the name implies, but it is not the same as postmodern philosophy. Capitalist economic theory has influenced both consumerism and individualism, two worldviews examined later in this book. It is a mistake, however, to equate either with capitalism or, for that matter, to assume that capitalism is the only influence on these systems. Thus, we will examine worldviews in their everyday expression, not their more purified theoretical forms, because that is how most people experience them and are drawn under their influence. (This also, by the way, cuts down significantly on the number of footnotes.)

Our second departure from the traditional model is to approach worldviews as more than just intellectual systems. Some readers will take us to task for this because they define worldview as an intentional attempt to frame answers to the deepest questions in life. Such attempts consciously begin with the aim of directly addressing questions about God, reality, knowledge, goodness, human nature and other foundational questions. Most of the lived worldviews we will examine do not start here. Nevertheless, as we will see, they imply answers to all of the questions that theoretical worldviews attempt to address. Moreover, the effect of our lived worldviews is the same sought by their theoretical cousins. They tell us what we should love or despise, what is valuable or unimportant, and what is good or evil. All worldviews offer definitions of the fundamental human problem and how we might fix it. When you get right down to it, every worldview attempts to answer the question “What must we do to be saved?” Regardless of whether it comes to us as a theoretical construct or is soaked up by osmosis from culture, our worldview will have a deep impact on how we view our universe, ourselves and our actions.

Because these hidden worldviews do what theoretical worldviews do (propose answers to fundamental questions and shape our lives), we do not hesitate to use the term worldview to describe the systems in this book. While we do not reject the validity of the intentional, rational examination of these questions, we think it stops too soon. The reality of life is that, while humans are rational beings, we are not just rational beings. The vast majority of us do not commit to a worldview by initiating a purely intellectual comparison of competing philosophies and choosing what appears to be the most coherent one. We don’t just think our way into worldviews, we experience them.

For most of us, our worldviews come to us more like a story or faith commitment rather than a system of ideas we select among a buffet of intellectual options. It is certainly the case that we are able to extract ideas that characterize each worldview, and this will occupy a significant amount of our attention in each chapter. Nevertheless, we want to be aware that, for most of us, worldviews are not primarily systems of interlinked ideas and beliefs, but they are experienced, absorbed and expressed in the midst of life.

Real-Life, Whole-Life Worldviews

If what we have said so far makes sense, it means that the entire worldview enterprise is a lot messier than is often implied by many books on the topic. James Sire’s understanding of worldview helps illuminate some reasons behind this messiness. As he defines it, “A worldview is a commitment, a fundamental orientation of the heart, that can be expressed as a story or in a set of presuppositions (assumptions which may be true, partially true or entirely false) which we hold (consciously or subconsciously, consistently or inconsistently) about the basic constitution of reality, and that provides the foundation on which we live and move and have our being.”[2] We will break Sire’s definition down into pieces slowly, but it is important from the beginning to clarify what he means by heart. Our culture tends to speak of the heart in reference to feelings or emotions. Sire reminds us, however, that the biblical concept of heart is much richer than this. It includes the emotions, but also encompasses wisdom, desire and will, spirituality and intellect. In short, the heart is, “the central defining element of the human person.”[3]

Equating heart with the entire person helps us identify one important factor that contributes to real-life worldview messiness. Worldviews are not just cognitive constructs in which the relative amounts of truth and error included in them determine the relative success or failure of our lives. Real human beings, beings with “heart,” are multidimensional; our lives possess physical, economic, psychological, political, spiritual, social and intellectual facets. This is why we intuitively recognize that a person with a clear and coherent grasp of intellectual truth still lives a less than complete life if they are economically careless or a psychological basket case (or, we would add, spiritually indifferent). To isolate the intellectual component as the exclusive concern of worldview formation, as many worldview books do, is reductionistic. It condenses a real multidimensional person to a single aspect of his or her actual existence. To be sure, our intellect is important, but if taken in isolation it fails to put complete and real people in the picture.

The charge of reductionism is one you will hear frequently throughout the following chapters because the strength of each worldview we examine also turns out to be its “Achilles’ heel” when that insight is absolutized. Consumerism, for example, correctly reminds us that we are finite beings who perish unless we consume at least some of our environment’s resources. Consumerism’s big mistake, however, is that it defines us solely as physical, consuming beings. Stated otherwise, consumerism is a reductionistic worldview because it absolutizes our physical and economic dimensions and gives insufficient attention to remaining aspects of human existence. Other worldviews, in turn, absolutize some other facet of our experience to the exclusion of others.

As you may anticipate, then, part of our argument is that Christianity avoids and corrects the reductionisms of these competing systems and offers a full-orbed account of human life. Thus, we will find much that we can consent to and learn from within non-Christian worldviews. At the same time, we maintain that any perspective that fails to do justice to every God-created dimension of human life cannot be described as a Christian worldview. To put it in the language of Sire’s definition, if “heart” refers to the whole person, we must pursue a wholehearted worldview that avoids reductionism.

Worldviews as Story

If Sire’s definition of worldview as a “heart orientation,” a set of commitments that encompasses the entire person, reveals one factor that clutters up our task, his suggestion that worldviews can be told as a story discloses a second messy element in our approach. The usual mode of operation in worldview books is to compare and evaluate propositional systems, which because they are systems, are neat and orderly. Stories, on the other hand, are not quite as tidy. However, we believe that the concept of story as a metaphor for worldview is more true-to-life than a recital of propositions that one believes to be true, for two reasons.

The first reason we prefer the concept of worldview as story is that we believe that our knowledge of God is revealed in a manner that is more analogous to a narrative than a set of propositions. It doesn’t take a deep investigation of Scripture to discover that it is not written as a logically constructed, tightly interconnected and cross-referenced system of truthful propositions. We may certainly be able to distill from the Bible such a system, but it does not come packaged in that way. Instead, as we will develop in chapter ten, Scripture’s overall structure resembles an epic story stretching from creation to history’s consummation, encompassing smaller stories of God’s interaction with people over a broad span of years and cultural contexts. This bigger narrative of God’s involvement with us, what we will call “God’s story,” provides the foundation on which we attempt to discern a Christian worldview and the broad horizon against which we all live our individual lives (or stories).

Second, in addition to God’s revelation coming in a manner similar to story, our worldviews unfold in a storylike manner. Consider how we come to know others. We do not discover who someone really is by asking for a set of propositions they assent to, although this may play a part. Instead, we gain insight into a person’s identity by learning where they come from, key life experiences, what they love, what sorts of relationships they have and a multitude of other storylike features. While we may talk about these matters in propositional terms, even these propositions are products of our experiences. Thus, while propositional beliefs are an essential aspect of worldview examination, these spring from the messy process that we will call “our story.”

Our Story and Worldview Formation

At birth, we arrive in a world filled with competing visions of purpose, truth and goodness, and we experience them in a multitude of ways. Worldviews come at us, not as fully-formed systems of interrelated ideas, but in bits and pieces. We encounter them through national heritage, religion, family influence, the educational system, peer groups, various media and countless additional sources. They are transmitted by these sources through such diverse forms as music, political speeches, advertising, unsolicited advice from friends or family and, yes, via our coffee-at-Starbucks conversations. And sometimes what is not said explicitly in these different modes of communication shapes our worldviews as much as what is said. In short, these influences are so pervasive throughout culture that we may not even see them at all.

Moreover, worldview formation, like a story, is not a static affair. Every good narrative, including our own, has a dynamic quality. Like stories, lives have a beginning, a middle and an ending that include specific contexts, unique characters, plot twists, conflicts or crises, along with resolutions that set up the next episode. As a result, even when the fundamental outlines of our worldview hold up over a lifetime, the details go through modifications based on our psychological development, new events or relationships, exposure to new ideas or a number of other factors.

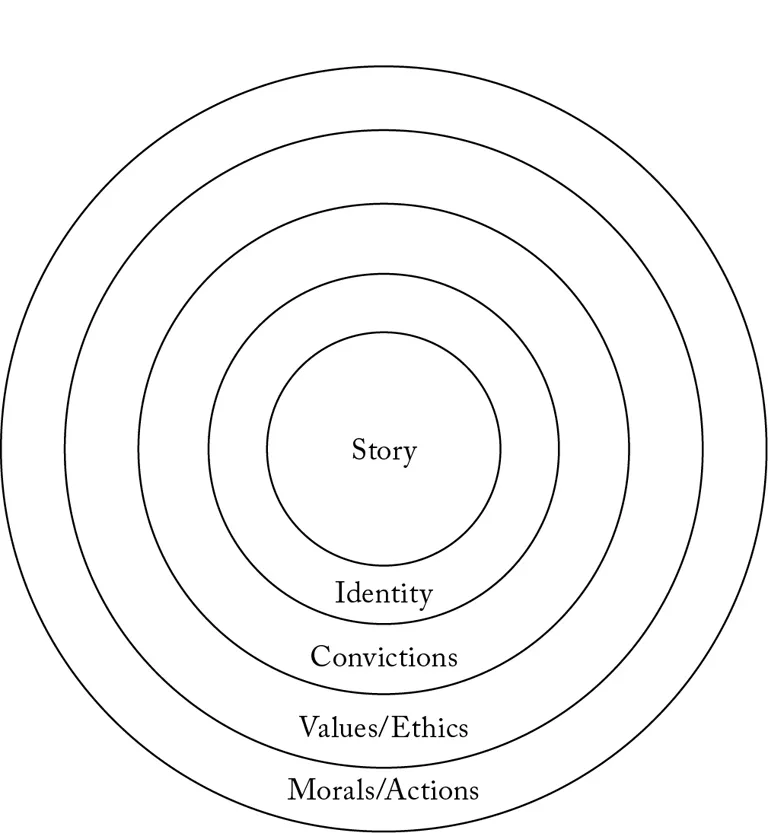

As the story unfolds, however, the sequence, actors and plot development are only the most visible features. In reality, our stories are structured, in large part, by forces that reside beneath the surface. My actions manifest the subterranean influence of my self-understanding, my convictions and my values. Things that happen to me and around me, many of them beyond my immediate control, provide the setting for my story. Nevertheless, what occurs in the various chapters, what my character becomes, is also molded by what I believe and value. Thus, in the following diagram we will trace the components of our story, our worldview, as they radiate from our interior stories toward external expression and action.

| Story: | The central narrative of our life |

| Identity: | How we see ourselves and presents ourselves to others |

| Convictions: | Those beliefs that make up how reality works for us |

| Values/Ethics: | What we believe we should do and what we take to be our highest priorities |

| Morals/Actions: | The realm of doing that includes all of our activities |

Figure 1. Transformation model (developed by Dr. Steve Green)

Story: Moving Toward Action

In the opening scene of Fiddler on the Roof, Tevye says that, because of tradition, “everyone knows who he is.” That is what our story does; it gives us an identity. The identity level of our being encompasses such things as our concept of success or where we believe we fit into the scheme of things. In the myriad of relationships—with God, myself, others and the physical world—my story provides an interpretive grid that expresses the importance and value of the various “others” I encounter. If my identity is invested in financial well-being rather than in friendships, I may n...