eBook - ePub

Counting the Cost

Christian Perspectives on Capitalism

- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

If Christians want to accelerate the world's transition out of abject poverty, they need to examine the role of capitalism.

Counting the Cost helps readers begin with the truth of Scripture. It then relies on the economic realities that come from our Godgiven design as the foundation for enabling readers to think critically about capitalism.

We live in an unprecedented time in human history. The number of people living in abject poverty is decreasing at an unprecedented rate. Capitalism has played a major role in lifting people out of such poverty, yet many raise legitimate concerns. Does capitalism hurt the poor? Promote materialism? Harm the environment? Allow the rich to get richer at the expense of everyone else? Is capitalism really the best system for organizing societies and the economies that keep them running?

This edited volume of articles by noted economists and theologians takes an honest and empathetic look at capitalism and its critiques from a biblical perspective.

Counting the Cost helps readers begin with the truth of Scripture. It then relies on the economic realities that come from our Godgiven design as the foundation for enabling readers to think critically about capitalism.

We live in an unprecedented time in human history. The number of people living in abject poverty is decreasing at an unprecedented rate. Capitalism has played a major role in lifting people out of such poverty, yet many raise legitimate concerns. Does capitalism hurt the poor? Promote materialism? Harm the environment? Allow the rich to get richer at the expense of everyone else? Is capitalism really the best system for organizing societies and the economies that keep them running?

This edited volume of articles by noted economists and theologians takes an honest and empathetic look at capitalism and its critiques from a biblical perspective.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Counting the Cost by Art Lindsley, Anne Rathbone Bradley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism Thirty Years After

MICHAEL NOVAK

It is not often that a new form of political economy appears in history, fills a need, and takes root in universal discourse. When I first showed a prospective publisher the title of The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism,1 he objected to the word “capitalism” in the title. It was a term of such denigration, he thought, as to have become irredeemable. To alter the title, I demurred, would have been to accept a falsely contrived definition of the term. It would have been to surrender without a fight. The point is that those who in each generation disparage capitalism mean by “capitalism” something quite false—in fact, so out of touch with reality that they should be ashamed. For instance, they define capitalism as constituted by three things: the market, private property, and private profit. The Soviet idea of socialism entailed the abolition of all three. But those three are not the essence of capitalism. Instead, they designate the traditional economy known from the beginning of civilization.

My plan for this chapter is to begin with the definitional issue, then to discuss the immense changes in political economies of the world during the past thirty years or so. After that, I describe the case of democratic capitalism in the United States, which is constituted by laws and systems that regulate and support the dynamism of creativity and invention. I conclude with reflections on the fragility of free societies, the driving question of how best to help the poor, and the underlying biblical inspirations of democratic capitalism.

The Definitional Issue

The definition of capitalism offered in virtually every English-language dictionary is decidedly flat. See Merriam-Webster, for instance:

an economic system characterized by private or corporate ownership of capital goods, by investments that are determined by private decision, and by prices, production, and the distribution of goods that are determined mainly by competition in a free market.2

What I propose, however, is a more dynamic understanding of capitalism:

the invention-based economic system made possible by laws protecting intellectual property, plus personal habits of economic initiative, enterprise, and practical wisdom, and in which the main cause of wealth is fresh ideas, ventures, and exercised know-how.

Further, I would add that capitalism replaces both the agrarian economy, in which the chief source of wealth is land, and the mercantile economy, in which the chief source of wealth is international shipping and trade. It is also useful to distinguish capitalism from socialism by noting their asymmetry: socialism is the name of a dream in which political, economic, and cultural authorities are centralized in one unified system; whereas capitalism designates only the economic system, ordered by both separate and independent political and cultural systems.

Thus understood, capitalism refers to a new system that came fully into being in the eighteenth century, one whose results are exactly opposite to many projections. Karl Marx said its effect would be the immiseration of the poor.3 Adam Smith used the term “universal opulence” to describe the aim of the system he identified in its early beginnings, and of course in the title of his great book, he spoke of the wealth of nations, not individuals, and explicitly included Africa and the Americas (South and North) in his discussions.4 Smith identified new inventions and new and enterprising ideas as the chief cause of the creation of steadily greater wealth among all nations. He also pointed out how in North America, wealth was being created from the bottom up, from the small farms, resulting in capital funds that over time built the factories that produced previously unavailable goods. The central idea of capitalism is that wealth is created by insight, know-how, and discovery, as in Smith’s illustration of the pin machine.5 Universal wealth is best created not by slavery or serfdom, and not by governmental direction from the top down, but by free women and free men using their own inventive and industrious minds to serve the largest public they can reach.

To reiterate: what I mean by “capitalism,” and what capitalism really is, is a new economic system that arose in history, ripening at about the end of the 1700s, not known in its full form to the ancient, medieval, or even early modern world. It is considerably more than a market system, or a system of private property, or a system of private accumulation of profits. All those features belong to ancient, medieval, premodern, and traditional systems. In the biblical period, there was certainly private property; otherwise “Thou shalt not steal” (Exod. 20:15 KJV) made little sense. Jerusalem was nothing but a marketplace at the juncture of three continents; it became modestly rich neither by industry nor by fertile agriculture. And profits became gifts that contributed to the building of the glorious temple. So these three characteristics—property, markets, and private profits—by no means define what was new about the modern system of economy lately christened “capitalism.” (By the way, private profits are often invested soon in public companies contributing to the common good, making widely available inexpensive breakfast cereal, for example.)

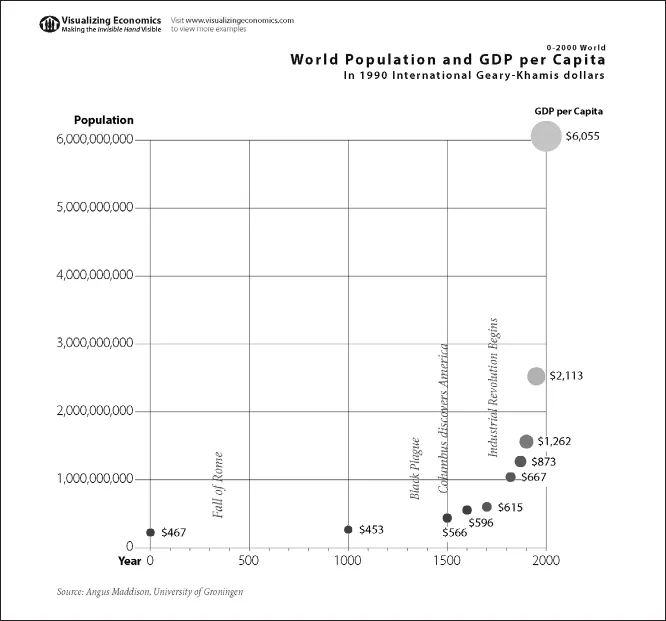

During most of the time in which the aforementioned earlier systems flourished, the economic world was virtually static. Not much changed from the time of Christ until the late eighteenth century. Only then, at about the year 1800, did the economic wealth of the world’s population shoot almost straight upward from the virtual flatline of all prior history. See, for example, the following chart:6

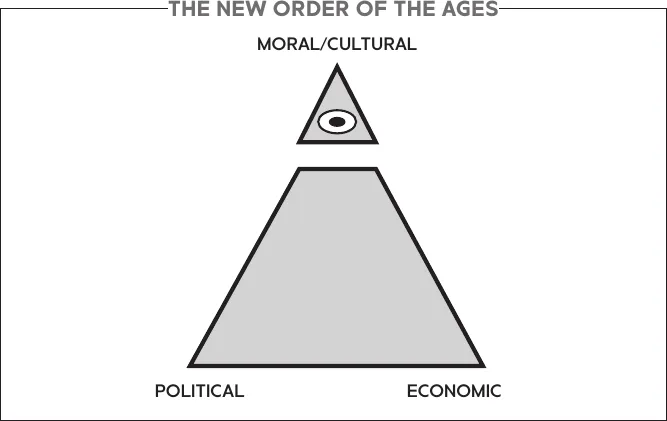

A further important clarification: the term “capitalism” by itself fails to capture the full range of effects of the new system which Smith referred to as the new “system of natural liberty.”7 Indeed, the new economy modified the traditional forms of polity and sharply spurred the demand for popular representation. It also promoted the building of new cultures by giving wider scope to commerce, especially to the gift of invention. A new political ideal was born: that of the commercial republic. Such a republic called for new virtues of civic republicanism: the seizing of personal responsibility and new habits of self-government, both in private and public life. In brief, the new system had not only an economic dimension, but political and cultural dimensions as well. This new system is best illustrated by a triangle, for these three dimensions—political, economic, and cultural—are all essential to a proper understanding of capitalism.

Given the long grip on the imagination of older models of polity, economy, and culture in Europe, the full scope of the new system could not be grasped. It was first announced under the name Novus Ordo Seclorum on the Great Seal of the United States and dated MDCCLXXVI. It could not be grasped, in fact, for another two generations, until Alexis de Tocqueville had the brilliant idea of going to investigate these novelties for himself. He reported his early findings in Democracy in America.8

In the eighteenth century, a host of thinkers had established the more complex term of “political economy” to add to the traditional subject matter of Aristotle’s Politics. At least these two terms are required to express the complex social system required for human liberty and flourishing: not just politics alone. For human liberty and human flourishing are fulfilled by neither politics alone nor economics alone. Rather, they require economic activity within a free polity, under the rule of law, and through the daily practice of personal habits of wisdom and self-control. James Madison, Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and their colleagues referred to the intellectual movement that led to this new conception as the new science of politics.9 Unlike all previous thinkers who had written on such affairs, these thinkers recognized the need for the larger concept of political economy.

When I proposed the idea of “democratic capitalism” in the 1980s, it was as a new name for the sort of political economy that characterized the free world, one toward which many of the unfree were now willing to work, a political economy of full human flourishing. Democratic capitalism means a system of natural liberty, requiring both political and economic liberty—but also more. Prior to those two is the acute need for a moral and cultural system shaped by new institutions and new personal habits. True liberty must be derived from self-control, and such liberty is best ordered by laws. Hence the need for a third science, the science of moral ecology, to discern all the institutions and personal moral habits essential for the flourishing of self-governing people. Under this view, liberty does not mean freedom from all restraints; rather, liberty means ordering one’s own life—that is, self-government—for the sake of full human flourishing, through reflection and deliberation. Democratic capitalism, therefore, is a system of three liberties: political liberty, economicliberty, and moral/cultural liberty (liberty in religion and conscience, in arts and science, and in cultural expression).

Without due attention to the interactions among these three systems, arguments pitched against democratic capitalism fall like arrows short of their target. Those vital interactions are the whole point of the concept and of the united “system of three systems” that it represents.

During the thirty years since this threefold system was first put forth, many critics have attacked it only in amputated form. Some think of it as no more than a libertarian system, concerned with economic liberty only, exaggeratedly individualistic, indifferent or even antithetical to welfare programs for the poor, unconcerned with the public good, focused solely on markets and private profit. Others think of it as libertarian mainly in the moral sense: pivoting solely on the ego of the individual (as in the thoughts of Ayn Rand), her pleasures, her contentment, her will-to-power. But in truth, the criteria of democratic capitalism require attention to all three dimensions of human flourishing: economic, political, and moral/cultural. This threefold complexity may be suggested by the flags of free societies. Typically, they have three colors, as if to signal the complexities of a full concept of liberty. This illustration is fanciful, but its vividness may help the mind grasp the threefold system.

Tremendous Effects around the World

During the past three decades, tremendous changes have taken place in the political economies of more than a hundred nations. When Ronald Reagan took office in 1981, the huge populations of China and the Soviet Union had communist political economies, and India was governed under a Fabian (mildly socialist) economy.10 The majority of the rest of the world lived under fairly fierce dictatorships, including most of Latin America, Africa, Southeast Asia, eastern and central Europe, North Korea, Cuba, and nearly all of the Middle East except Israel.

My own reconsiderations about political economy began before the Reagan administration, at a time when the Jimmy Carter administration still hoped to serve two full terms. The previous Democratic nominee for president, George McGovern (in whose presidential campaign I eagerly served), was even further to the left than Carter. Both McGovern and Carter pointed to inequality as the main theme they would focus on. Old warriors like me remember well McGovern’s proposed “demogrants”11 for wealth redistribution and Carter’s war against inegalitarian horrors such as three-martini lunches.

During the 1980s, most of the communist and socialist nations of the world were already quietly dropping their failed economic systems and turning to markets, private property, and personal enterprise. Why? Because one system didn’t work and the other did. India started the tide, the Chinese saw its success, and the Eastern Bloc nations saw themselves as wrongly deprived. Meanwhile, in the United States during the Carter years, Keynesian policies led to previously unheard-of “stagflation”12 and economic malaise. During the four Carter years, ever-growing inflation wiped out a third of the value of those on fixed incomes, throwing millions into poverty.

Whether capitalism or socialism is a better system for dramatically reducing poverty was thus a well-settled question by the mid-1980s. As I wrote in The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism, the most underreported fact of the twentieth century was the death of socialism. It was dead, all right, but that underreported death would take a little more time to become overpoweringly evident to all. The global turn toward capitalism began not long after, in 1989, and within twenty-five years some two billion people had begun moving from communism and socialism toward capitalism, thence out of poverty and into steadily advancing standards of living. These numbers were most notable in China, India, and the former Soviet Union and its captive nations.

By 2008, the world’s population had risen to roughly seven billion people, most of them living longer than ever before through the blessing of sophisticated new medicines pioneered in advanced capitalist countries. Today, there are still about a billion more persons who need to be raised up out of poverty. Succeeding in this project is the number one moral priority of our time.

To repeat an important point made earlier, Adam Smith called his book An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations—nations, not individuals. The task laid out in that book is a social mission, not an individualist one, and it will not be completed until all nations and all persons are included within the upward sweep of the inventive economy.

I started to write about democratic capitalism in the 1970s in an effort to explain to my overseas friends (and to myself ) just what the U.S. new order is (i.e., what is this Novus Ordo Seclorum?). One could not learn this simply by reading the political philosophers and political scientists who didn’t write much about economics or cultur...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter One The Spirit of Democratic Capitalism Thirty Years After

- Chapter Two Human Flourishing and the Bible

- Chapter Three Is Capitalism Contrary to the Bible?

- Chapter Four A Christian Critique of Capitalism: Is Capitalism Based on Greed?

- Chapter Five Is Capitalism Exploitative?

- Chapter Six The 1 Percent: Is Income Inequality Evidence of Exploitation?

- Chapter Seven Who Benefits in Capitalism?

- Chapter Eight Capitalism and Poverty: Economic Development and Growth Benefit the Least the Most

- Chapter Nine Capitalism and Consumerism: Delighting in Both Creations and the Responsibilities of Affluence

- Chapter Ten Do Global Corporations Exploit Poor Countries?

- Chapter Eleven Is Capitalism Bad for the Environment?

- Chapter Twelve Capitalism and the Cultural Wasteland

- Conclusion

- Contributors

- Index