eBook - ePub

Why College Matters to God, Revised Edition

An Introduction to the Christian College

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

A brief introduction to the unique purpose and nature of a Christian college education for students, their parents, teachers, and others.

The new edition expands the discussion of Christian worldview beyond intellectual analysis to include actions and attitudes. Sections on the Christian mind, redemption, and cultural engagement have been revised to incorporate the recent insights of Christian thinkers such as Andy Crouch, James Davison Hunter, Gabe Lyons, Mark Noll, and James K. A. Smith.

The new edition expands the discussion of Christian worldview beyond intellectual analysis to include actions and attitudes. Sections on the Christian mind, redemption, and cultural engagement have been revised to incorporate the recent insights of Christian thinkers such as Andy Crouch, James Davison Hunter, Gabe Lyons, Mark Noll, and James K. A. Smith.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Why College Matters to God, Revised Edition by Rick Ostrander in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Higher Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 INTRODUCTION

Christian Worldview and Higher Education

ONE of my favorite Far Side comics depicts a herd of cows grazing on a hillside. With a surprised look, one cow says, “Hey, wait a minute! We’ve been eating grass!” Like most Far Sides, the comic works because it uses animals to depict a universal truth: In society we often do things automatically without ever asking the question “Why?”

Take college, for example. A Tibetan herdsman visiting America would notice a strange phenomenon. Among the middle and upper classes of society, young people around the age of eighteen complete a certain level of schooling known as “high school.” Then millions of them pack up their belongings and move to a residential campus to live with other young people, most of whom they have never met. For the next four or five years, they complete an assortment of classes that collectively comprise what is called “undergraduate education.”

Just what are these classes? First, they take “general education” or “core curriculum”—classes such as English literature, history, natural and social sciences, and philosophy—the kind of stuff that people have been studying for centuries. Along with the core, students take classes in what they call a “major” area of study: a subject that they are most interested in or one that they (or their parents) believe will yield the best career prospects. Amid all of this coursework, the students find ample time for eating, socializing, competing in athletics, and playing Halo in the dormitory.

It all may seem quite normal to those of us who have gone through or are going through the process. But our Tibetan herdsman probably would be hard pressed to see the purpose in all of it. His perplexity would increase if he visited a private Christian college, where chances are students pay more money for a narrower range of academic programs and more restrictions on their social lives.

Of course, there are a variety of reasons why students choose to attend a Christian college. For many of them, it’s the perception of a safe environment. For others, it’s a particular major that the school offers; or perhaps the Christian emphasis in the dormitories, chapel, and student organizations; or the school’s reputation for academic rigor and personal attention from Christian professors. It may even be the likelihood of finding a Christian spouse at a religious college.

None of these features, however, is unique to a Christian college. For example, if it’s safety you’re looking for, you could just as well attend a secular college in Maine, which boasts the nation’s lowest crime rate. Moreover, most state universities have thriving Christian organizations on campus that provide opportunities for fellowship and ministry—and more non-Christians to evangelize as well. One can also find good Christian professors at just about any secular university. One of the most outspoken evangelical professors that I had as a college student, for example, was my astronomy professor at the University of Michigan.

The real uniqueness of a Christian college lies elsewhere. Simply stated, the difference between a Christian university and other institutions of higher education is this: A Christian college weaves a Christian worldview into the entire fabric of the institution, including academic life. It is designed to educate you as a whole person and help you live every part of your life purposefully and effectively as a follower of Christ. Such a statement will take a while to unpack in all of its complexity; and that is the purpose of this book. If properly understood, however, this concept will enable you to thrive at a Christian college and to understand the purpose of each class you take, from English literature to organic chemistry. But first we must establish four foundational concepts, the first of which is the notion of worldview.

The difference between a Christian university and other institutions of higher education is this: A Christian college weaves a Christian worldview into the entire fabric of the institution, including academic life.

1. What is a worldview?

About a decade ago, the film The Matrix enjoyed popularity among youth pastors and those who like using movies to discuss deep ideas. That’s because amid the fight scenes and big explosions, The Matrix forces us to ponder the age-old philosophical question posed by Rene Descartes back in the 1600s: How can I know what is really real? The film begins with the protagonist, Neo, as a normal New York City resident. But gradually he becomes enlightened to the true state of reality—that computers have taken over the world and are using humans as power supplies, all the while downloading sensory perceptions into their minds to make them think they are living normal modern lives. Neo achieves “salvation” when he accurately perceives the bad guys not as real people but as merely computer-generated programs.

The Matrix thus challenges us to recognize that some of our foundational assumptions about reality—that other people exist, that this laptop I’m writing on is really here—are just that: assumptions that serve as starting points for how we perceive our world. If my friend chooses to believe that I am a computer program designed to deceive him, it’s unlikely that I will be able to produce evidence that will convince him otherwise. Furthermore, as Neo’s experience in the film indicates, shifting from one perception of reality to another can be a rather jarring, painful process.

In other words, The Matrix illustrates the notion of “worldview”—that our prior assumptions about reality shape how we perceive the world around us. A worldview can be defined as a framework of ideas, values, and beliefs about the basic makeup of the world. It is revealed in how we answer basic questions of life such as, Who am I? Does God exist? Is there a purpose to the universe? Are moral values absolute or relative? What is reality? How should I live my life?

We can think of a worldview as a pair of glasses through which we view our world. We do not so much focus on the lenses; in fact, we often forget they are even there. Rather, we look through the lenses to view the rest of the world. Or here’s another metaphor: If you have ever done a jigsaw puzzle, you know that the picture on the puzzle box is important. It helps you know where a particular piece fits into the overall puzzle. A worldview does the same. It’s the picture on the puzzle box of our lives, helping us to make sense of the thousands of experiences that bombard us every day.

Two important qualifications about this notion of “worldview” are important at the outset. First, a worldview is not the same thing as a “life philosophy.” A philosophy of life implies a rational, deliberately-constructed, formal system of thought that one applies to one’s world. But worldviews go deeper than that. A worldview is pre-rational and instinctive. It is shaped by my experiences and the community in which I live more than by logical analysis. One could say that my worldview originates in my heart as well as my head. It’s the means by which I “know” not only that 2 + 2 = 4 but that I love my wife, that my redeemer lives, and what the appropriate “social space” is in our culture. As Christians, we should desire to align our worldview with the truth of Scripture and with sound reason (and that’s an important purpose of college). But we need to recognize at the outset that a worldview is rooted in who we are at our deepest level, not just our intellect. As C. S. Lewis remarked in The Magician’s Nephew: “For what you see and hear depends a good deal on where you are standing; it also depends on what sort of person you are.”

Second, it’s important to note that worldviews are about actions, not just beliefs. As one scholar has stated, it is a view of the world that governs our behavior in the world. To return to the example of Neo in The Matrix: His new understanding of the nature of reality results in a fundamental change in how he lives his life. Indeed, one could say that the actions and practices that order our lives reveal what our actual worldview is, regardless of how we might describe that worldview on paper. In other words, a worldview is a way of life, not just a set of ideas.

We cannot help but have a worldview; like the pair of spectacles perched on my nose, my worldview exists and is constantly interpreting reality for me and guiding my actions, whether I notice it or not. Neo begins The Matrix with a worldview; it just happens to be an incorrect one, and he has never bothered to think critically about what his worldview is. One of the main purposes of college, therefore, is to challenge students to examine their worldviews. Which brings me to the next foundational concept.

2. All education comes with a worldview.

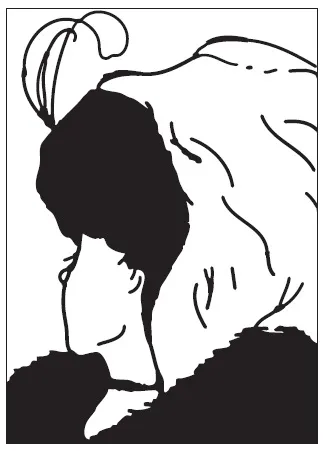

Worldviews shape not just our individual lives but universities as well. There was a time when scholars seemingly believed that education was completely objective. Professors in the secular academy, it was claimed, simply “studied the facts” and communicated those facts to their students. Now we know better. All education, whether religious or secular, comes with a built-in point of view. Even in academic disciplines, the worldview of the scholar shapes how the data is interpreted, and even what data is selected in the first place. Nothing illustrates this fact better than the following optical illusion commonly used in psychology:

All education, whether religious or secular, comes with a built-in point of view.

Some viewers immediately see an old lady when they look at this drawing. Others see a young woman. Eventually, just about anyone will be able to see both (if you cannot, relax and keep looking!). This is because while the actual black and white lines on the page (the “facts,” so to speak) do not change, our minds arrange and interpret these lines in different ways to create a coherent whole. Moreover, this is not something that we consciously decide to do; our minds do this automatically. We cannot avoid doing so. Neither can those who visualize the drawing in different ways simply argue objectively about whose interpretation is the correct one, since their disagreement is not so much over the facts of the drawing but over what those “facts” mean.

In a more complex way, a similar process occurs whenever scholars work in their disciplines. Historians, for example, agree on certain events of the American Revolution—that on April 18, 1775, Paul Revere rode through the New England countryside shouting “The British are coming!”; that the Continental Congress signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776; that on December 25, 1776, George Washington and his army crossed the Delaware River and surprised Hessian soldiers at Trenton. But what do these facts mean? How are they to be arranged into a coherent whole? When did the American Revolution actually begin? Was it motivated primarily by religious impulses or by Enlightenment philosophy?

Historians argue constantly over such questions, and the answers to them depend in part on the worldview of the historian, who selects and interprets historical data according to certain assumptions about how politics and societies change—ultimately, basic assumptions about what makes humans tick. Thus, a Marxist historian who believes that ultimately human beings are economic creatures motivated by material rewards will likely interpret the American Revolution in a way that emphasizes the financial self-interest of colonial elites. The Christian who believes that human motivation often runs deeper than just economic interests will likely emphasize other factors such as ideas and religious impulses. The “facts” of the Revolution are the same for each historian, but like Neo’s perception of his world, the interpretation of those facts is influenced by the scholar’s worldview.

Or, to cite an example from science: Biologists generally agree about the makeup of the cell, the structure of DNA, and even the commonality of DNA between humans and other life forms. But do such facts demonstrate that human beings evolved from other life forms, or do they indicate that some sort of intelligent being used common material to create humans and other life forms? The answer to this question is not simply a matter of evidence; it is influenced by the scientist’s assumptions about ultimate reality.

More generally, not just academic disciplines but entire universities operate according to worldviews. One of the universities that I attended, the University of Michigan, had a worldview that shaped its culture; it was just never stated as such. In fact, one could argue that like many secular universities, my alma mater displayed a multiplicity of worldviews. In the classroom, my courses typically were taught from a perspective known as scientific materialism, which could be described like this: the material universe is all that exists; human beings are a complex life form that evolved randomly over the course of millions of years; belief in God is a trait that evolved relatively recently as a way for humans to explain their origins, but now this belief is no longer necessary. Thus, academic inquiry is best conducted when one sets aside any prior faith commitments.

Student life at Michigan, however, typically embodied a different worldview—that of modern hedonism or devotion to pleasure. This worldview holds that in the absence of any higher purpose to life, personal pleasure and success are the greatest values. Thus, you should get good grades in college since that is your ticket to a successful career. However, you should not let studies interfere with having a good time, generally defined in terms of parties, socializing, and of course, college football.

Paradoxically, however, a third worldview governed much of campus culture, one best described by the phrase tolerant moralism. According to this worldview, intolerance, injustice, and abuse of the environment are the great evils of modern society; racial and cultural diversity and ecological responsibility are the ultimate goods. The actions of individuals and the university community, therefore, are rigorously scrutinized according to how they measure up to these moral values, and anyone from the custodian to the president is liable to censure if their words or actions are seen as detrimental to these causes. A few years ago, for example, the president of Harvard University lost hi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Preface to the Second Edition

- Preface

- 1 Introduction: Christian Worldview and Higher Education

- 2 Where We Came From: A History of Christian Colleges in America

- 3 Living Largely: The Doctrine of Creation

- 4 Not the Way It’s Supposed to Be: The Doctrine of the Fall

- 5 Broadcasting Mozart: The Doctrine of Redemption

- 6 Integrating Faith and Learning: A Basic Introduction

- 7 An Education That Lasts: Thinking Creatively and Globally