![]()

Part One

Beyond Self and Individual Identity

![]()

1

The Way We See It

Social Constructionism and Practical Theology

I asked my youth to draw pictures of their families. With markers in hand and blank sheets of paper before them, they began drawing their family portraits. Round circles for heads, straight lines for the arms and body, each separated by space. Unique physical attributes delineated each figure, and objects signified parents’ jobs. All of my youth’s drawings pictured families made up of individuals—except for one.

Tony’s family picture was horrendous. It had one body, four heads, eight arms and eight legs. And the pairs of legs and arms were all different. Several youth laughed at his picture and called it ridiculous. I imagine the apostle Paul experienced similar ridicule from members of the church in Corinth when he suggested viewing Jesus as a head and his followers as feet, ears, hands and so on. Tony’s perspective was different, but profound.

“Why are you laughing?” Tony asked, holding the paper protectively to his chest.

“Because it’s not real,” Heather hissed.

“Is your picture real?” I asked.

Heather looked down at the lines and circles that represented her family. “No,” she said, shrugging.

“Whose picture is real? If I gathered your family and took a picture with my phone, would that be real?” I asked.

My youth stared at me, shaking their heads.

“Who taught you how to draw? Talk? Write?” I went on.

“Our parents,” they said in unison.

“Do you think your drawing is just ‘your drawing’? Or do you think your families have influenced the way you hold your pencil, how you talk to others, how you view others? So even in the act of drawing, your family presses firmly on your pencil.”

For my youth, Tony’s drawing did not represent a “real” family because our Western reality teaches us that we are fundamentally separated and distinct people. But to pretend that my familial relationships do not exist while they are not physically present is an illusion. Dominican priest Albert Nolan stated this well:

We remain one flesh all our lives, no matter what illusions of independence and separateness we may develop in our minds. In reality we are intertwined, interconnected, and interdependent. None of us could survive without others. We would have no language and no knowledge. We belong together. We are one.[1]

In an episode of the TV reality show Undercover Boss, Steve Choice, CEO of Choice Hotels, said in a choked voice, as he let the tears come, “I know my mom was proud of me, but I know she would be really proud of me today.” Steve’s relationship with his mother, which no longer existed physically, continues to shape him. Are we really as separated as what we see with our own eyes? Or are we as connected as Tony’s picture illustrates?

My youth’s diverse pictures were not right or wrong; they each presented a portrait of their family. If I wanted to know what role each family member played and their occupation, Heather’s portrait would have provided me with more information. I am emphasizing Tony’s family portrait here because the interconnectedness that he sees is absent in most of our youth ministry practices.

Tony’s perspective is a simple shift in the way of seeing his family. He sees the interconnectedness of his family—even when they are not physically available. How do you view your family? Church? Ministry?

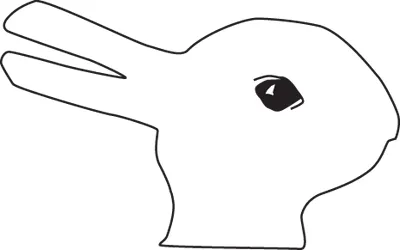

I presented figure 1.1 to my youth, and said, “Don’t tell me what you see. Reflect on what you would add to the picture. What’s missing? What kind of environment would you draw if you were the artist?

“A pond,” Jon shouted.

“A pond? Do you want to drown it?” Paige asked, wrinkling her brow.

“Why?” Jon asked. “What would you add?”

Paige let out a frustrated sigh. “A forest, briar patch and some carrots. Duh!”

“Why would you feed a duck carrots?” Jon asked, staring at her.

“Because I’m not feeding a duck; it’s a rabbit!”

“It’s both a duck and a rabbit,” said Stephan, who had seen the picture before.

Jon and Paige looked at the drawing a second time and laughed when they finally saw the other’s duck, the other’s rabbit.

The picture illustrates how our perspectives change how we see and understand the same object. Why is it that Jon, Paige and Stephan couldn’t help but see it in certain ways? A simple shift in perspective can reveal entirely different animals.

A Change in Perspective

Perhaps you have had shifts in perspective that have changed the way you view people, situations and yourself. I’ve had my share of those too. As mentioned in the introduction, my encounter with the Gergens and social constructionism shifted my view of self, family, youth and youth ministry practices.

In the initial research for my dissertation, I studied individual youth. I believed I could better understand my youth and how to minister to them if I began with each individual. As the motto goes, I attempted to meet youth at their point of need. I would observe Cassie and try to understand what made her tick. I thought that if I could figure out Cassie’s outward influences, I would know what affected her mental processes. Or if I could figure out her mental processes (and deficits), I could discover what caused her actions—or lack of action.

Instead of pitting the outer and inner against each another (psyche versus social and nature versus nurture), I attempted to place them in a relationship. It was no longer either/or but both/and. Therefore, I understood Cassie as a product of the relationship between her psyche and social influences, and I adopted the term psychosocial. I wrote more than two hundred pages on ministering to youth from a narrative psychosocial perspective. Here’s the issue, though: in both her outward influences and her mental processes, Cassie was never alone. Social constructionism helped me see there’s no I in psychosocial.

Through the lenses of social constructionism, I began to see that my view of human action was limited to the individual, causing me to miss a fuller understanding of my youth. Within the framework of social construction, I had room to shift my perspective of Cassie’s individual action to her co-action in relationships.[2] The focus and attention was no longer on the individual, but on the person in relationships.

At first, this concept seems like it removes the internal in favor of the external—namely, Cassie is solely determined by her relationships. Though she is not determined by her relationships, she mutually constructs her world with her mom, dad, sister, brother, teacher, friends and so on. In the context of youth ministry, I would ask, “Who does Cassie become through her relationships with her youth pastor, mom, dad, sister, brother, friends and teachers?” She is a different person in each of these relationships. Therefore, the focus is not on her internal workings or how the external changes the internal, but on the collaboration that occurs differently in each of her relationships. The shift to the coordination of the relationship moves us beyond several age-old arguments that divide nature versus nurture, social versus psyche and outside versus inside.

Social Constructionism

Social constructionism is not a singular and unified theory; it is better understood as an unfolding dialogue among a wide variety of scholars and practitioners. The pivotal idea of social constructionism is that we create our world through our relationships and through the language we use and the stories we share.[3] This description appears simple and straightforward, but as we unpack its implications, we will see its complexity—and the richness it offers the youth in our ministries.

As Westerners, we view the world from an individualistic perspective—a view that many practical theologians share when engaging in theological reflection and praxis. Yet social constructionism illuminates our relational formations that are eclipsed by individualism. Our tendency to begin with the individual shapes how we see God, read Scripture, communicate, interact with others, understand youth development, minister and so on. Social constructionism is a tool that we can use to remove the lenses of individualism so that we can recapture the ministry of Jesus in our relationships and in the stories we share with our youth.

Individualism blinds us to how connected we are. Our choices and decisions really do affect those around us. If we do not see our connectedness, we are like the man who went fishing with two friends. In the middle of the lake, he decided to drill a hole under his seat in the bottom of the boat. The other two men began to panic and scream, “What are you doing?” With calm detachment, he said with a sneer, “What is it to you? I am only making the hole under my seat.”[4] Social construction helps us to see that we are all in the same boat. Living as if we are not is like drilling a hole under our seat and thinking that we are affecting no one but ourselves.

Language: The Lens Through Which We See and Create the World

Relationships come before all that is intelligible. This idea is central to social constructionism. We wouldn’t see a duck or a rabbit if no one had ever taught us the terms for those animals. Of course, the animals exist, but as we describe and explain them, they become real for us in particular ways.

A cow to many Western children means milk. A farmer sees a cow as income. A meat lover sees a steak. A Hindu bows and worships. How do you see a cow? What we deem a cow, calf, bull, cattle and so on depends on the relationships we have established with others and the language we have learned to label and classify such beings. A cattle breeder would laugh at our oversimplification of cows, because there are over eight hundred breeds of cattle. Not until we are introduced to the language of the cattle breeder can we see the complex world of cattle the way he does.

You probably don’t see brick buildings the same way that I see them. I have been a brick mason most of my life. I try to show people rowlocks, sailors, soldiers, stretchers, quoin corners, head joints, bed joints, Flemish bonds, herringbones and Spanish bonds, but they see only bricks and patterns. Introducing brick masonry terminology allows people not only to see but also to appreciate brick buildings in completely different ways. At first people have a difficult time understanding what they’re seeing, but the more they use the brick mason’s language, the more their perception and their experiences change. So it really does make a difference what kind of language we use in youth ministry and how we talk and share stories—particularly biblical stories—with our youth.

Relationships and language are vital to who we are and who we become. This emphasis on the coordination of relationships and language (in particular narratives) in human action was a natural segue for me to get back into the basics of practical theology.[5]

Social constructionism became a tool that grounded my practical theology within the context of relationships. Seeing the world through the relationships and stories that form us—and seeing our actions through them—leads us into a deeper, thicker and richer understanding of youth ministry. For Christians, it invigorates two of the most prominent forms of ministry: relationships (to God and people) and stories (biblical stories and shared stories).

Social construction coupled with practical theology equipped me to ask questions concerning the relational co-action between youth and youth pastor, youth and church, youth and adults. How well are we as youth pastors doing with our “God language” in everyday ministry? Our words do not just state information, but construct a world with our youth. What kind of vocabulary is our youth ministry providing so that they can talk about God?

Youth can’t articulate, understand and have a meaningful experience of God without God language. “The lone individual might have an experience of God, but without any theological language [stories of God] he would have no way of knowing what the experience was,” philosopher and theologian Nancey Murphy said.[6] The more stories—shaped and framed by the biblical story—youth ministers provide, the more opportunities youth have to “story”—frame and reframe—their experiences of God in...