- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Writing Skills for Social Workers

About this book

As a social worker, you are required to communicate in writing for a wide range of purposes and audiences.

This text guides you through all you need to know to develop your social work writing skills:

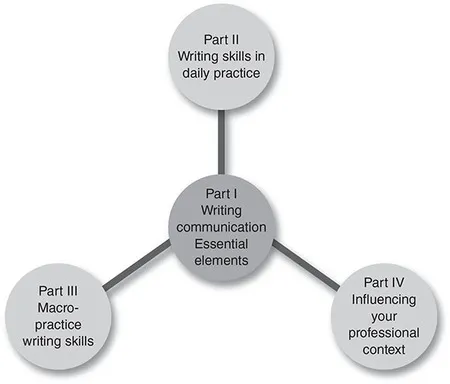

- Essential elements of written communication

- Writing skills in daily practice

- Macro-practice writing skills: obtaining resources and creating change

- Influencing your professional context

Now with two new chapters on writing for local mass media and writing for social media.

Hot tips for effective writing, reflective exercises & further reading are included in every chapter to help you cement your skills and become a confident and effective written communicator.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Writing Skills for Social Workers by Karen Healy,Joan Mulholland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I Essential Elements Of Written Communication

Figure 1.1 Elements of

professional writing in social work

1 Written Communication: Getting Your Message Across

Introduction

Social workers engage in a wide range of writing practices across a variety of practice methods and contexts. Historically, the social work profession has emphasized the importance of skills in spoken communication but has accorded less attention to effective written communication (Prince, 1996). Fortunately, social workers are becoming more aware of the importance of writing skills for direct practice with service users and for achieving such goals as improved team communication, influencing policy, and contributing to the knowledge base of social work. Indeed, the national educational standards for professional social workers in many countries, including the United Kingdom, USA and Australia, now require that social work graduates build and demonstrate a skills base in professional writing, particularly in writing case records and professional reports (see AASW, 2012; CSWE, 2015; QAA, 2016). Furthermore, the social work subject benchmark statement of the British Quality Assurance Agency (QAA) states that graduates should be able to communicate effectively by ‘verbal, paper based and electronic means’ (QAA, 2016: 19). Similarly, the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE, 2015: 7) in the United States requires graduates to demonstrate professional demeanour in ‘oral, written, and electronic communication.’

The emerging awareness of the importance of professional writing skills is perhaps due to the increasing volume of written work required in social work practice and the growing number of social work responsibilities that involve written communication. For example, social workers face increased accountability requirements to maintain accurate written accounts of their work, and to report on the efficacy of social service programmes. This book aims to enhance your effectiveness in written communication by providing a comprehensive guide to writing for social work practice contexts and professional purposes. We include in this edition a focus on writing by both paper based and electronic forms of communication. The good news is that many of the principles for effective spoken communication also apply to written communication. However, many areas of communication also require specialist writing skills, and by mastering these skills you can improve your usefulness as a social worker. This book is dedicated to that goal.

Writing In Everyday Practice

Social workers spend a great deal of their working day involved in written communication. Most social workers write emails, letters and case notes every day. Social workers are also regularly required to undertake other types of writing tasks, such as writing professional reports, legal statements and funding applications. Increasingly too, social workers are writing in an online environment. Many of our writing tasks such as case records and funding applications may occur online. This form of writing is usually in a standardized format which may require completion of specified information categories and may involve character count limits. In some professional contexts, social workers are also using texts and instant messaging to communicate with service users (DeJong, 2014; Haxell, 2012). In addition, social workers may engage in social media platforms, such as Facebook and Twitter, particularly in community practice. As we shall discuss, the growth and diversification of communication platforms is reshaping the writing process. In this book, we will discuss how to maximize the effectiveness and impact of your writing on paper and in online environments.

Writing skills are just as important as spoken skills in the knowledge and skills base we need for professional social work practice. Indeed, with the growth of online communication across a range of practice contexts, writing skills are more important than ever. Internationally, social work educational programmes are now being held to account for developing students’ capacities for professional writing. For example, in the United Kingdom, the QAA (2016) national benchmark statement for social work standards requires that social work students must learn to ‘Write accurately and clearly in styles adapted to the audience, purpose and context of the communication’ (Section 5.15.vii). In addition, the QAA statement requires that social work students ‘Demonstrate persistence in gathering information from a wide range of sources and using a variety of methods … these methods include electronic sources’ (Section 5.12.i) and learn to ‘Assimilate and disseminate relevant information in reports and case-records’ (Section 5.12.iii). Similarly, in Australia the national educational standards documents require that, at a minimum, social work students demonstrate the capacity to keep accurate and comprehensive records in accordance with ethical principles and relevant legislation.

This chapter will use an approach specifically designed to consider the language aspects of writing – words, grammar, structures and so on. We will show how each social worker can find the language to suit the formalities in the written forms of social work, without losing a sense of individuality. We will examine the language of writing, and will supply a series of reflective examples and exercises. We recognize the analytic skills you have already acquired in spoken communication, and we build on those as we consider your written communications. We will examine the problems faced in putting the complexities of social work ideas and assessments into the words and sentences that will be understood by those who will need to read them.

The Similarities Between Spoken And Written Communication

Let us begin by considering the similarities between spoken and written communication. Our purpose in making this comparison is to show that you already possess some of the skills required for effective written communication, and to identify those aspects of spoken communication that can or cannot be transferred to written communication.

Social workers are well used to managing spoken communication with clients, managers, colleagues and others. Your training in supportive talking and sensitive listening enables you skilfully and successfully to conduct client conversations and interviews. And you have learnt to hear the nuances of spoken language as your colleagues talk in team meetings and case conferences, and to respond with care and attention to what their language tells you. These skills are at the core of your daily work as a social worker. But the social services profession also requires you to be skilled in communication through writing. You have to translate the spoken interactions you have with clients, and make them available for others through your written case notes and records; and many other parts of your practice require you to write for an audience, some of whom you may never see. You will have to inform different people what happened in your spoken interactions, to explain what you think the interactions meant, and to design reports on them to fit the requirements of the audience. Your written assessments of clients’ circumstances may form the basis of your own and others’ decisions for action. Indeed, your written assessments may play a crucial part in a chain of events and decisions well beyond your direct involvement with a particular situation. It is important to remember that written communications are social interactions, and that they serve to inform, explain to or persuade others for many social service purposes, and are as much part of your daily communications as speaking and listening. You need to work as hard on your written communications as you do on your spoken ones.

As your experience of client interactions grows, new occasions for writing occur: you may want to communicate your ideas on social work practice to others in your profession, or to inform the community of a community services initiative. As a practitioner you may also want to influence the formal knowledge base of social work. Your practice experience can provide an ideal vantage point from which to critique and develop social work knowledge for practice. The most effective way of influencing the knowledge base is through written communication in public forums, especially professional journals and conference proceedings. Through these formal communication channels you can have national and international influence on the profession.

The Differences Between Speech And Writing

Using written communication is not easy. After all, most of us have a good deal more experience with speaking and listening and with non-verbal communication than with writing. We develop writing skills long after we learn many other forms of communication skills.

When the two skills of speaking and writing are compared, a number of differences can be seen. Firstly, Speaking occurs quickly in many cases, and because of this any errors which occur in words and sentences are rarely noticed. Also, since the speaker is present, he or she can add non-verbal information such as gestures or facial expressions to supplement the message to the listeners. Indeed, studies indicate that up to 85 per cent of communication in face-to-face interactions is conveyed non-verbally (Harms, 2015: 36). But in writing, the words and sentences have to work alone, and what appears in the document or online is all that people have to make meaning of the communication. Speaking occurs in the presence of others. You may know your audience beforehand or you may get to know them during the course of talking together. Writing, on the other hand, has no audience present, and in some cases writers may not know who exactly their audience is, or even when and where their communication will be read. In the speaking situation the others who are present usually join in the talk, and so the talk will change direction and develop new tones and topics. Topics normally drift during interviews, conversations and meetings; it is often commented on at the end of a talk session that the last topics are very different from the first, and people remark that it is hard to know how the changes of topic came about. In writing, on the other hand, the topic is under the control of the writer from start to finish, and well controlled writing makes readers feel that the writer knows where the communication is going, that there is an underlying plan, and that thought has gone into the topic choice and development. Readers feel comfortable in the hands of a writer who acts as a good guide through the communication so that the arduous task of reading is made easier. For example, students often state that they prefer those lecturers who deliver tidy lectures, with good identification of each section and a clear introduction and conclusion. Such lectures are easy to follow and understand, and they enable students to take good notes on them: you could reflect on your own experiences in this regard.

Second, because speaking happens in the presence of others, listeners are able to ask questions if the speaker is unclear, or to make corrections if the speaker gets something wrong. Writing does not make this allowance, so writers have to put themselves in the position of the audience and anticipate what questions may be raised, and present the material so that any potential questions, or disagreements, are handled within the writing.

Third, in spoken communication the audience’s attention may be less focused than in written communication, because in spoken communication the audience is often at the same time giving attention to what they will say as soon as the speaker finishes. Because their attention is divided, they may miss something that is said, even losing entire ideas and important aspects of what the speaker is saying. However, readers of a written communication pay closer attention. Readers can pause and think about what has been written, and can go back over a difficult idea at any point. This means that written documents can and perhaps should be more complex and densely packed with ideas and meanings than is the case with speech. The density means that extreme care has to be taken with every element of the complex document. In addition, the structure and planning of the document must be carefully designed so that the complexity is made as easy to follow as possible, and the language must be precise enough to withstand being reread several times. The care that readers will take in reading the document needs to be matched by the care with which it is written or they will be disinclined to take it seriously.

Fourth, once speaking is over, it is lost except in memory (unless it is recorded). But memories of spoken interactions can be inaccurate...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustration List

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Part I Essential Elements Of Written Communication

- 1 Written Communication: Getting Your Message Across

- 2 Managing Information For Writing

- Part II Writing Skills In Daily Practice

- 3 Writing In Direct Practice: Email, Texting, Messaging And Letters

- 4 Writing Case Records

- 5 Writing Reports And Affidavits

- Part III Macro-Practice Writing Skills: Obtaining Resources And Creating Change

- 6 Writing For Local And Mass Media

- 7 Writing For Social Media

- 8 Writing Funding Applications

- 9 Writing Policy Proposals

- Part IV Influencing Your Professional Context

- 10 Writing A Literature Review

- 11 Writing Journal Articles And Conference Papers

- 12 Professional Writing: Now And Into The Future

- References

- Index