eBook - ePub

Reflective Practice and Personal Development in Counselling and Psychotherapy

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reflective Practice and Personal Development in Counselling and Psychotherapy

About this book

Reflective practice is a vital part of your counselling and psychotherapy training and practice. This book is your go-to introduction to what it is, why it is important, and how to use different models for reflection and reflective practice to enhance your work with clients. It will support your personal development and professional development throughout your counselling training and into your practice.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Reflective practice: An overview

Core knowledge

Some of the key terms guiding this chapter are:

- •Different models for reflection and reflective practice.

- •‘Reflection in’ and ‘reflection on’ practice, as distinguished by Donald Schön. This includes considering ‘on-the-spot experiments’ as well as systematic retrospective learning.

- The concepts of espoused theory and theory-in-use, as introduced by Schön and Argyris to explore the interesting gap between what professionals say they do and how they actually practice.

- Double-loop learning, which aims to highlight underlying values and assumptions in decision making at work.

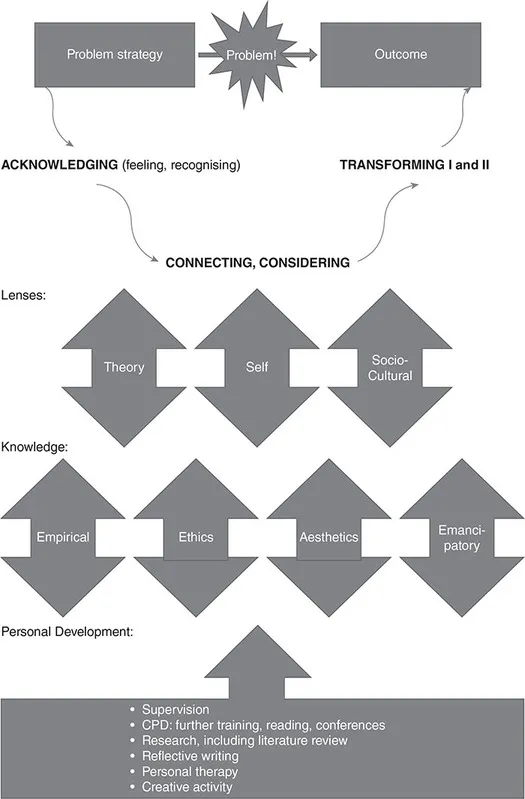

- The TSS-ACCTT ‘map’ aims to support you in ‘looping back’ on critical decisions. TSS stands for Theory, Self and Socio-culture as filters or lenses to loop back through when considering difficult decisions and problems. ACCTT reflects phases from Acknowledging (sensing, feeling, noticing) a problem, to Connecting and Considering it in context of your self, your theory and socio-cultural framing for practice, before Transforming practice and sometimes developing therapeutic Theory with your new learning.

Reflective practice

Reflective practice rests on a critical appreciation of theory, self and the socio-cultural context for our practice. It involves ‘looping back’ on events in our practice from different angles guided by an openness for continuous transformative learning. It has been documented, critiqued and developed across different disciplines. In this chapter, both forerunners’ and later thinkers’ theories on reflective practice will be explored, starting with Kant’s still relevant definition of ‘reflection’:

Reflection is not concerned with objects themselves, in order to obtain concepts from them directly, but is a state of the mind in which we first set ourselves to discover the subjective conditions under which we can arrive at concepts. (Kant, 1781/2007: 264)

We will explore some of the critiques about reflective practice as ‘too broad’ versus ‘too descriptive’. We will return to some key principles suggested by Donald Schön who coined the phrase ‘reflective practice’. Reflective practice will be explored with the therapists’ needs and interests at heart. The personal development angle to reflective practice involves listening to, considering and exploring what you might need to thrive and develop as part of your relational practice.

Both simple and complex

Simply put, reflective practice is about how we make our decisions in practice. The complexity becomes obvious when we think of explaining ‘actions’ in movement-related practices, like skiing, driving a car or acting as a stuntman. Most actions rely on learnt, internalised and intuitive knowledge to progress; stopping to explain and consider what exactly might be going on – for instance in scientific terms – is neither helpful nor an option. Some practices offer more time to reflect in action than others: psychotherapy offers a particularly well-suited practice for reflecting-in-action. The underpinning interest for reflective practice revolves, in short, around the mystery of ‘thinking on ones’ feet’, e.g., how to without much thinking time respond to events decisively and effectively. Approaching the process ‘the other way around’ can sometimes help to highlight the complexities involved in this: starting with not acting can be helpful to explore how learnt, internalised as well as intuitive responses come into play. The following exercise is intended to help to support you explore the space between your experiences of something within a therapeutic relationship, and informed or automatic responses.

Activity 1.1 Hearing the other

You need a partner for this exercise, which revolves around listening without any interruption. You will each take turns to talk about a topic of your own choice for five minutes, without any interruptions by the other at all.

Checklist:

- Have you got a watch?

- Have you agreed on what to do if any unforeseen strong emotions should arise?

Activity: Talk about a chosen, personal subject for five minutes. The listener will remain silent, listening without any interruptions at all.

Afterwards, for the listener:

- How did not intervening make you feel? When – if at all – did remaining silent seem like an issue? What might you have wanted to put forward, at what point?

- Concentrate on connecting with all your responses during your listening – what happened inside you when listening?

- How can your response be understood in context of your personal background?

- How – if at all – does your modality help to understand your responses?

Activity: Take turns.

Discuss and share experiences around your learnt, internalised responses versus spontaneous, perhaps surprising reactions during this ‘session’. Did you have time to consider the difference between the two?

The ‘TSS-ACCTT’ map

The conundrum of moving from an experience to some form of knowledge – ideally guided by informed decisions made whilst in action – is, as suggested, both simple and complex. What Schön (1983) famously describes as the ‘swampy lowlands of practice’, has been explored from multiple perspectives. The aim of the ‘TSS-ACCTT’ map (Figure 1.1) below is to support your thinking around your own reflective practice. TSS stands for Theory, Self and Socio-culture as contexts, or ‘filters’ for your reflections. ACCTT stands for Acknowledging, Connecting, Considering and Transforming practice as different phases of reflective practice.The TSS-ACCTT map integrates different approaches to reflective learning as conceptualised by, for instance, Schön (1983), Kolb (1984), Gibbs (1988, 2013), Johns (1995), Mezirow (2009) and Taylor (2006) in their models for experiential and transformative learning. Acknowledging, connecting and transforming represent, as suggested, ‘phases’ which move from simply noticing, sensing, feeling to connecting with a problem and critically considering it in context of your modality, with the view of informing and transforming your own – and sometimes others’ – practice through your new learning. Personal development plays a key role in this process, your support and ongoing learning will be paramount. We will consider learning in context of different types of knowing, including sensing, feeling (aesthetic) and empirical knowing.

Figure 1.1 TSS-ACCTT Model

Reflective practice across different disciplines and time

The significance of reflective practice is well-documented across different disciplines. A simple literature review shows widespread references in, for instance

- education (Gibbs, 2013; Jay & Johnson, 2002; Rogers, 2001)

- social work (Ixer, 2016; White, Fook, & Gardner, 2008)

- nursing (Goulet, Larue, & Alderson, 2016; Johns, 1995)

- general psychology (Binks, Jones, Fergal, & Knight, 2013; Lewis, Virden, Hutchings, Smith, & Bhargava, 2011)

- applied sport psychology (Anderson, Knowles, & Gilbourne, 2004), including areas like sports coaching with studies titled: ‘[a]nother bad day at the training ground: coping with ambiguity in the coaching context’ (Jones & Wallace, 2005: 121).

Ambiguity is a common theme in the studies relating to reflective practice, as is the prospect of ‘learning from critical experiences’. The studies tend to refer to forerunners of reflective practice like Schön (1983), Kolb (1984) and Gibbs (1988) in particular.

Forerunners

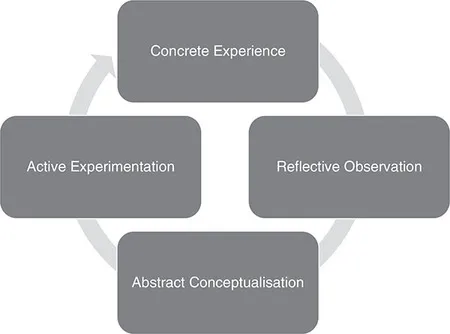

Kolb referred to learning as ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ (Kolb, 1984: 41). Kolb’s theory presents a cyclical model (Figure 1.2) of learning over of four stages. The learner actively experiences an activity, then consciously reflects back on that experience, followed by making sense of it and experimenting with new solutions.

Figure 1.2 Kolb’s transformation of experience as the basis for knowledge

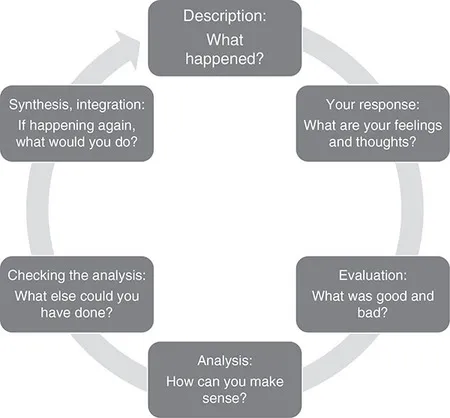

Gibbs (1988, 2013) added a significant emotional dimension to the reflective practice as highlighted in (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3 Putting emotions into reflection, as adapted from Gibbs (1988, 2013)

New models

The number of suggested models for reflective practice seems to be growing (Black & Plowright, 2010; Goulet, Larue, & Alderson, 2016; Nguyen, Fernandez, Karsenti, & Charlin, 2014). Based on a systematic literature review, Ruth-Sahd identifies outcomes of the reflective process:

- Integration of theoretical concepts to practice

- Increased learning from experience

- Enhanced self-esteem through learning

- Acceptance of professional responsibility and continual professional growth

- Enhanced critical thinking and judgement making in complex and uncertain situations, based on experience and prior knowledge, thereby enhancing patient care

- Empowerment of practitioners

- Increased social and political emancipation

- Improvement in practice by promoting greater self-awareness. (Ruth-Sahd, 2003: 490)

Ruth-Sahd synthesises a broad definition to cover the many references, with reflective practice as ‘an imaginative, creative, nonlinear, human act in which educators and students recapture their experience, think about it, and evaluate it’ (Ruth-Sahd, 2003: 450).

Ruth-Sahd criticises at the same time this broad and often blurred consensus of meaning, suggesting that ‘authors and researchers define reflective practice by using their own lenses, worldviews, and experiences’. This broad definition mystifies and ‘blurs a consensus of meaning’. Practitioners are ‘being encouraged to … promote reflective practice [but] shown very little evidence that it actually improves practice or results in learning’ (Ruth-Sahd, 2003: 490).

Reflective practice is likely to disappoint if we seek a neat and tidy structure for it. Another, more recent systematic literature review is offered by Marshall (2019). His overview of literature across different professions resulted in the suggestion of four overarching themes within reflective practice, namely as a cognitive, integrative, iterative and active process.

- Cognitive. Used to make sense of complex and ambiguous problems. reflective practitioners are ‘theoreticians of practice’ (Marshall 2019: 399). Marshall refers, for instance, to Schön (1983) and Kolb (2014) who suggest searching for tentative, explanatory hypotheses which can be ‘tested’ through subsequent experiences and reflections.

- Integrative. Reflective practice involves analysing and synthesising different ideas and perspectives to integrate new experience with existing knowledge. This includes using reflective practice as a means of exploring one’s own meaning-making processes including theory, emotions, values and beliefs to integrate new perspectives with the already known.

- Iterative. Reflective practice is an ongoing cyclic process with frequent returns (looping back) to one’s interpretation of experiences and ideas.

- Active. Reflective practice includes active involvement based on deliberate, conscious attempts to make sense of an experience or idea and to integrate, or implement, this learning into new practice.

Systematic questioning focusing different perspectives

Reflective practice always involves systematic questioning, but with different types of knowledge to the forefront. Beverley Taylor asserts that ‘it simplifies the enormous task of thinking about reflection’ if we think in terms of ‘three main types of reflection’ (Taylor, 2006: 15). Each type of reflection can be used alone or in combination with the others.

- Technical reflection is based on the scientific method and rational, deductive thinking, and will allow you to generate validated empirical knowledge through rigorous means so that you can be assured that work procedures are based on scientific reasoning.

- Practical reflection provides a systematic questioning process that encourages you to reflect deeply on role relationships, to locate their dynamics and habitual issues.

- Emancipa...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- About the author and contributors

- 1 Reflective practice: An overview

- 2 Personal development

- 3 Your support and development

- 4 Reflecting on relationships

- 5 Reflecting on practice with research

- 6 Emancipatory knowing

- 7 Developments within reflective practice

- 8 Evaluating our practice

- 9 The vulnerable researcher Harnessing reflexivity for practice-based qualitative inquiry

- 10 How creative writing aids our professional transition

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reflective Practice and Personal Development in Counselling and Psychotherapy by Sofie Bager-Charleson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Psychotherapy Counselling. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.