eBook - ePub

Evaluation Practice for Projects with Young People

A Guide to Creative Research

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Evaluation Practice for Projects with Young People

A Guide to Creative Research

About this book

This straightforward and original text sets out best practice for designing, conducting and analysing research on work with young people. A creative and practical guide to evaluation, it provides the tools needed to bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and applied practice.

Written by an experienced, erudite team of authors this book provides clear, pragmatic advice that can be taken into the classroom and the field.

The book:

- Provides strategies for involving young people in research and evaluation

- Showcases creative and participatory methods

- Weaves a real world project through each chapter, highlighting challenges and opportunities at each stage of an evaluation; readers are thus able to compare approaches

- Is accompanied by a website with downloadable worksheets, templates and videos from the authors

This is the ideal text for postgraduate students and practitioners who work with young people in the statutory and voluntary sectors.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Evaluation Practice for Projects with Young People by Kaz Stuart,Lucy Maynard,Caroline Rouncefield in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Evaluation Context

Chapter Overview

- The challenges in evaluating work with young people

- The difference between formal, non-formal and informal learning

- The challenges and dilemmas workers face when they are asked to design, implement and analyse evaluations

- The difference between proximal and distal outcomes

- The approach to evaluation presented in the rest of this book.

Work with Young People

Youth work is founded in a set of core values and principles which, besides guiding youth work practice, informs the practice of evaluation with young people. However, although these values are key to practice, they make evaluation with young people a difficult, complex endeavour and can present the youth worker with a range of practical and ethical challenges when called upon to carry out evaluations. Historically, the values underlying youth work do not sit easily with traditional approaches to evaluation, particularly those forms which adopt a ‘scientific methodology’ or which fail to put the young person at the heart of the evaluation process. This chapter describes some of the current pressures placed on youth workers, the dilemmas evaluation poses and our responses to them. The discussion, methods, approaches and case studies we present are based on our experience of working with young people over a number of years and within various contexts. We believe the distinct purpose, values and approaches of youth work, and its basis in the principles and practices of informal and non-formal education, presents ‘evaluators’ with a range of challenges. However, we also believe that these challenges enable us to use a fresh perspective from which to address evaluation.

Challenge Number 1: The Distinctiveness of Young People’s Non-formal Learning

For readers who are not youth workers, the meaning of ‘youth work’ can be difficult to pin down. ‘Youth work’ has been used to refer to a wide variety of activities, from working with a group of scouts, running a youth club or making contact with groups of young people on an estate to addressing anti-social behaviour.

The definition of youth work used in this book is from the National Youth Agency in the UK:

Youth work helps young people learn about themselves, others and society, through informal educational activities which combine enjoyment, challenge and learning.Youth workers work typically with young people aged between 11 and 25. Their work seeks to promote young people’s personal and social development and enable them to have a voice, influence and place in their communities and society as a whole.Youth work offers young people safe spaces to explore their identity, experience decision-making, increase their confidence, develop inter-personal skills and think through the consequences of their actions. This leads to better informed choices, changes in activity and improved outcomes for young people. (NYA, 2014b)

As a learning experience youth work is influenced by key educationalists’ ideas, such as the importance of emancipatory education (Friere, 1972), the role of race, capitalism and gender in the perpetuation of oppression and the need to celebrate invisible histories and cultures (hooks, 1994), and the role of critical pedagogy and empowerment (Giroux, 2001; McLaren et al., 2010); it is important to revisit the principles of these key figures when planning an evaluation of youth work.

As the NYA quote above shows, youth workers are often defined as informal educators (Rosseter, 1987), and youth work is often described as an informal process (Merton et al., 2004; NYA, 2014b). We, and others, believe that the word ‘informal’ can be problematic, and it has been increasingly suggested that the appropriate term for planned interventions with clear purposes being applied throughout Europe is ‘non-formal education’ (Festeu and Humberstone, 2006).

When we talk about projects with young people in this book we refer to non-formal learning. Non-formal learning involves learning through planned activities that take place outside school or college, but which involve some form of facilitation. The evaluation practice described in this book can also be applied to formal and informal learning settings, but principally we refer to non-formal projects throughout this text. So what is the difference?

Non-formal learning is learning outside the formal school, vocational training or university system. Non-formal learning takes place through planned activities, in other words, activities that have goals and timelines. Non-formal learning involves facilitation. This does not equate to ‘teaching’ as the role of the student as an active participant is stressed. It tends to be short-term, voluntary, and have few if any prerequisites, although it can have a curriculum and can overlap with formal learning (Batsleer, 2008). Youth work is often non-formal in that there may be a session plan and intended outcomes. A session watching a DVD might, for example, have intended outcomes that include listening skills, discussion and increased awareness of the subject on the DVD. The session plan might also detail what the youth workers will do with the young people to enable them to gain the outcomes from watching the DVD.

Informal learning is learning that is not organised or structured in terms of goals, time or instruction. There is no teaching or facilitation and as such it refers to skills acquired through life and work experience in the private and social lives of learners. It also includes the informal learning that occurs around educational activities, rather than as an intended aspect of a planned educational intervention. Young people hanging out in the park together may learn social skills for example. This spontaneous informal learning may also occur in a formal setting, with young people, for example, learning about social norms in a classroom setting whilst formally being taught, say, geography.

Formal learning is planned learning that takes place in schools, colleges and universities. It involves a teacher planning a series of lessons that cover a curriculum and can be highly bureaucratic and institutionalised. The teacher may use interactive teaching styles, or may predominantly ‘transmit’ or tell the young people what they need to know. A lesson on citizenship for example may require the young people or ‘students’ to listen to the teacher, read a section of text, and then complete some comprehension questions.

The key difference between these forms of learning is the degree of power that young people have. In formal learning the young person has very little power over what is planned, delivered or assessed. In informal learning the young person has all the power. In contrast, non-formal learning shares power with young people and takes the development of the young people themselves and of their life-world as the point of engagement (Batsleer, 2008).

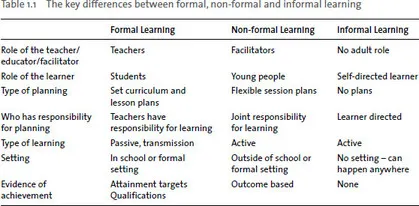

The differences between these types of learning are set out in Table 1.1. The difference between these three forms of learning is significant in evaluation as two of them are predisposed to having a predetermined set of outcomes to work towards, and one intentionally has no outcomes. Because formal learning is pre-planned, it is predictable and relatively straightforward to monitor and ‘measure’ through the attainment of targets at key stages, and eventually through qualifications (often called ‘hard’ outcomes). Non-formal learning is less predictable, although there are goals and timelines, these are flexible and outcomes are often more concerned with the social or personal development of the young person (‘developmental outcomes’ or ‘soft outcomes’). As a consequence, planning, implementing, monitoring and ‘measuring’ outcomes is a complex process. Informal learning is completely unpredictable and so even more difficult to monitor and ‘measure’. Perhaps because of this, formal learning has often been privileged as the ‘best’ way to learn, as it is simpler to evidence attainment.

Youth workers have championed the non-formal/informal approach to working with young people, as has the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO, 2012) who have recently called for the validation of non-formal and informal learning in the EU by 2015 to ensure that the outcomes of formal, non-formal and informal learning are equally valued. This drive is also championed by the Organisation for Economic Growth and Development (Werquin, 2010).

Unfortunately, this move comes with a cost. Given the nature, aims and practices of informal and non-formal education ‘demonstrating success’ has proved notoriously difficult. However, it is exactly these forms of learning that youth work practitioners are being asked to evaluate and demonstrate the ‘success’ of. It is clear that one of the challenges for people working with young people in informal or non-formal settings is to develop effective and appropriate ways of evaluating and demonstrating the success of their practice, of this distinct form of learning.

Pause for Thought

Think about a project that you have been involved in:

- How would you classify the type of learning? Identify critical elements within this using Table 1.1.

- Why does it not fit into other types of learning?

- What are some of the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ outcomes of the project?

Challenge Number 2: The Professional Context

The discussion of formal, non-formal and informal learning showed that previously formal learning has been privileged as it was possible to evidence outcomes and attainment in this style of learning. Education, and the well-being of young people more generally is often subject to changes in the political leadership of countries. This can lead to differences between countries at different points in history. Currently in the UK it is the age of evidence. Here, evidence currently counts above all else in the realms of policy making, health, social care, education and youth work. In the next section we identify some of the other recent pressures coming to bear on youth work at local, national and global scales, including drives for the free market economy, managerialism and individuation.

The free market economy

The drive for free market economy is based on assumptions that competition and user choice will raise quality as organisations compete to offer the best service to consumers. As youth work projects are pitched against one another in price wars for funding, the result may actually be a decrease in quality as the temptation is to reduce services to reduce costs (Baldwin, 2011: 188). Supermarkets, one could argue, need a free market economy to keep them competitive to ensure that their profits are balanced with low prices for customers. They deal with food commodities and profit margins. Youth services, on the other hand, do not have consumers who pay them money. They are largely funded by local authorities or trust funds. Forcing such organisations into competition does not therefore benefit the end consumer – the young person – nor are services necessarily improved by fierce competition. The free market economy drives evaluation to demonstrate the cost benefits of youth work.

The free market economy is now also a global phenomenon, with the United Nations and OECD developing many European and global databases of indicators showing how well countries manage to look after their young people (among other things). The first youth work indicators have just been developed by the Commonwealth, called the Youth Development Index (The Commonwealth, 2013). This index has measured educational, health, employment, and civic and political participation of young people aged 15–29 across all the Commonwealth countries. Some of the indicators, for example, are: D1.3...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustration List

- Table List

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Companion Website

- Introduction

- 1 The Evaluation Context

- 2 Evaluation Methodology

- 3 Evaluation Ethics

- 4 Types of Evaluation

- 5 Power

- 6 Planning Evaluations – An Overview

- 7 Collecting Data to Evaluate

- 8 Using Mixed Methodsin Evaluation

- 9 Analysing Evaluation Data

- 10 Writing Evaluation Reports and Presenting to Different Audiences

- Conclusion

- Glossary

- References

- Index