- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Researching Family Narratives

About this book

This edited book guides students and researchers through the processes of researching everyday stories about families. Showcasing the wide range methods and data sources currently used in narrative research, it features:

- Examples of real research into historical and contemporary family practices from around the world.

- Coverage of both traditional and cutting-edge topics, like multi-method approaches, online research, and paradata.

- Practical advice from leading figures in the field on how to incorporate these methods and data sources into family narrative research.

With accessible language and features that help readers reflect on and internalize key concepts, this book helps readers navigate researching family lives with confidence and ease.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Researching Family Narratives by Ann Phoenix,Julia Brannen,Corinne Squire in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Family Lives, Everyday Practices and Narrative Research

Key Words

- narrative

- narrative research

- family lives

- habitual/everyday practices

- research practice

Introduction

Researching Family Narratives is based on a series of projects that constituted a five-year methodological research programme running from 2011 to 2015, with funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) under the National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM). The programme was designed to develop and showcase methods and approaches that capture the complexity of the everyday in narratives of family lives across datasets.

The focus of Narratives of Varied Everyday Lives and Linked Approaches (NOVELLA)1, and of this book, is family life: different family members and different kinds of families living in different parts of the world and in different historical moments. As NOVELLA's name indicates, it took as its central concern the everyday practices of families. As we know from our own experiences of being part of different families, these practices are frequently taken for granted, but people's habits and their relation to society are very often negotiated within families, however ‘family’ is defined. Our focus in this book is on what family members do, and what they say they do, giving us insights into questions of identity, values, and how families understand their pasts and view possibilities for the future, across a range of settings and concerns, and a wide range of participants.

Across the social sciences, the study of everyday life is recognised as key to the understanding of identities, agency and social life (Back, 2015; Neal and Murji, 2015; Schraube and Højholt, 2015). Yet, all too often, attempts to research the everyday fail to capture the complexity of the mundane because the research methods used entail reductive simplification (Hollway and Jefferson, 2012), or attempt to represent complexity but cannot give sustained attention to more than a few cases (Hammersley, 2008).

In addition to the book's core concern with the study of everyday family life, its unifying theme is narrative research, that is, research into the ways in which people use symbolic language of all kinds to build up human meaning. As Kellas (2010) notes: ‘stories and storytelling are one of the primary ways that families and family members make sense of everyday, as well as difficult, events, create a sense of individual and group identity, remember, connect generations, and establish guidelines for family behavior’ (Kellas, 2010: 1). The book's central argument is that narrative is key to understanding the ways in which families are formed in different ways in different circumstances. It is about how they forge everyday, habitual family practices – in short, how they ‘do’ family (Morgan, 2011). In order to understand how families make meaning, narrative approaches are particularly suited to eliciting and to analysing the stories that family members tell themselves and others about their lives and everyday practices.

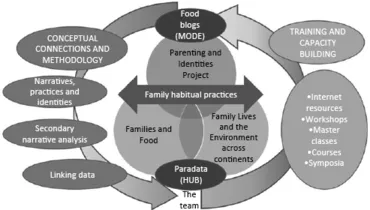

Researching Family Narratives and the work of NOVELLA are unique in taking a narrative approach to the ways in which research is practiced: in methods of data collection, analysis, interpretation and writing up. A general objective of NOVELLA was to drive forward the development of methodological practice. Its more specific aim was to bring a narrative approach to the analysis of existing datasets and the conduct of new research via a set of interlinked projects. The five research projects described below were joined by a focus on family habitual practices, and conceptual connections and methodology shown on the left of the Figure 1.1: narratives, practices and identities; secondary narrative analysis; and the linking of data across the studies. The studies were also united by the National Centre for Research Methods’ commitment to having its research programmes central to methodological training and capacity building, as on the right of Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Map of the NOVELLA research programme

In carrying out this analysis, we brought a narrative approach to data collected by a range of methods, including a multi-method approach (a mix of qualitative methods); biographical methods and semi-structured interviews; birth cohort data; diaries; oral histories; visual material; paradata; digitised material, mapping and walking methods. The book showcases these methods, some of which were used singly, some in a mixed quantitative and qualitative methods approach, and some in a mix of qualitative methods. Bringing together these datasets and analyses in the book provides a holistic sense of the range of sources that researchers may draw upon in understanding family lives, and how a narrative approach offers insights into families’ habitual practices and how they make meaning.

The methods were distributed across the chapters as below:

- International qualitative studies of family lives in relation to the environment conducted in Majority and Minority worlds, including interviews, photography, and ‘walking interviews’ (Chapter 2).

- Personal stories of men's lives as fathers and migrants, which were collected in the UK (Chapter 3).

- UK cohort data on fathering (Chapter 3).

- Archival data of different kinds (diaries, oral histories and visual material) concerning food practices in national periods of difficulty and food shortage (Chapter 4).

- Paradata written in the margins of questionnaires from a UK study of poverty (Chapter 5).

- Digital material (written and visual) consisting of online blogs on mothering (Chapter 6).

Researching Family Narratives also includes a chapter on the topic of reflexivity in which a narrative approach was applied by two doctoral researchers to conversations held over the course of their studies. In these conversations, they reflected on their different positionings in relation to their respective PhD studies and to the NOVELLA project to which their projects were attached.

A further chapter is devoted to the ethical practices of carrying out narrative research, in particular secondary analysis of datasets that spanned continents, cultures, time, language and epistemology.

Before going on to discuss the relevance of narrative approaches to the study of family life, we briefly make the case for their importance.

The rise of narrative research

The proliferation of narrative methods in the social sciences has taken place for four main reasons.

First, they offer a way simultaneously to keep individual lives and social positioning in view, while focusing on people's own accounts. In other words, they allow researchers to apply insights from ‘turn-to-language’ approaches, while situating individual meaning in social context and so enabling simultaneous micro-analysis of talk and interactions, and macro-analysis of wider social contexts (Phoenix, 2013). Unsurprisingly, such a complex endeavour generates a range of theoretical positions and a wide span of methodological approaches. For this reason, we are describing the field generally as ‘narrative research’, rather than for instance ‘narrative inquiry’ (Clandinin, 2013), the latter a more specific approach which sets out to work explicitly with narrative materials and to construct the researcher's own story in dialogue with those materials. Some researchers carry out analyses of material which is not clearly ‘narrative’, for instance, objects, and many do not involve the researcher as part of the story. Other researchers emphasise the importance of working with narrative materials, even of the co-construction of such materials with the researcher, but do not analyse those materials narratively. The breadth of possibilities opened up by narrative research's symbol-founded approach to the building of human meaning, across many different levels, means that in this book we want to keep in view both co-construction and the narrative analysis of both narrative and other materials, and to contextualise materials in their spatial, social and historical contexts.

Second, as Bruner (1990) argues, narratives are common and naturally occurring, with humans being homo narrans, storytelling animals. As a consequence, narrative research is often more open to its participants and to its audiences than other social science methods that appear to refer only to social science itself. This generality of narrative in human lives also allows for participatory or transformative narrative research, research that links academic to everyday and wider politics, and research that is concerned with narrative's relations to social justice and change (Bradbury, 2019; Fine, 2017; Plummer, 2019; Squire, 2020).

Third, narrative approaches are interdisciplinary, used in fields as varied as literature, art, law, anthropology, psychology, social history, cultural studies and sociology (Bruner, 2002). This inter-disciplinarity gives narrative research wide currency and strong possibilities for dialogues across fields that can lead to development and change. In addition, narrative research's inter-disciplinarity means that researchers have found ways to work with a wide range of materials. These include spoken narratives, both oral and transcribed, which are recorded and analysed at varying levels of complexity; written narratives like diaries, letters and auto/biographies (Stanley, 1995a, 1995b, 2004); visual materials such as paintings, photography and film; non-verbal, bodily narratives; internet narratives and narratives of spaces, objects and actions (Bell, 2013; Davis, 2013; Esin and Squire 2013; Hyden, 2013). This narrative multimodality has helped bring narrative social research into conversations with, for instance, historical and media studies that serve to expand and enrich the field.

Fourth, narrative methods enable the linking of theory and practice (Squire, 2005). Carolissen and Kiguwa (2018) have called these linked endeavours, ‘narrative as theory-method’. They have suggested that the dialogic working out of theory and method together in narrative research enables narrative researchers to investigate citizenship alongside identity, and the socio-historical alongside subjectivities. As a result, ‘narrative as theory-method’ produces a degree of fluidity, movement and engagement that is particular to this approach. In addition, narrative research's attention to theory and practice simultaneously allows for a full consideration of ‘context’, from the intrapersonal and interpersonal to the macro-political, also taking into account ‘reflexivity’, the researcher's analysis of their own multi-levelled contextual positioning.

Taken together, these advantages make narrative analysis particularly suited to the study of everyday practices – the repeated, familiar, predictable, habitual routines that are at the heart of the production of subject positions, identities and representations (Bourdieu, 1977, 1990; Davies and Harré, 1990; De Certeau, 2011). Indeed, the turn to narrative methods has partly happened because of the increased interest in subjectivity in the social sciences (McLeod and Thomson, 2009). People's stories tell us about their lives and the contexts shaping (and shaped by) them.

Given the proliferation of approaches and the growing popularity of narrative research, researchers are often uncertain about how to conduct narrative analysis and which version to employ. As a result, there is currently a need to increase skills in narrative analysis in the social sciences. That researchers are keen to enhance their skills is demonstrated by the high demand for training sessions on narrative research, particularly narrative analysis, around the UK. In order to maintain innovative and internationally leading research, it is important to share developments in narrative methods. This was a key element of the NOVELLA programme that enhanced the research practices of the team and the quality of the research. In addition, a major difficulty with narrative research is that it is extremely time consuming, both at the stage of data collection and in analysis. These factors make it difficult to do complete narrative analyses on more than a relatively small group of interviews and other types of data or on a limited range of narratives in any research project. As a result, many so-called ‘narrative projects’ rely on thematic analyses (also often underspecified) to gain a broad overview of their findings (Braun and Clarke, 2006). In this book, we endeavour to show how rich, rigorous and feasible narrative approaches can be applied to both gathering and analysing research materials.

The relevance of narrative research to the study of everyday family lives

This book fills a gap in both the narrative methodological literature and the family research literature by focusing on narrative research on everyday family lives. The practices of families constitute a large fraction of our habits in everyday living and in our interactional and emotional practices. Feminist and feminist-influenced scholars especially have positioned these familial elements as central to ‘the everyday’, but argue that they are understudied and simplified in social research (Morgan, 2011; Phoenix and Husain, 2007; Smart, 2007), including, as suggested earlier, in narrative social research and its considerations of method. On the other hand, many social researchers have explored normative and non-normative forms of family, and more recently, from an intersectional perspective as classed, sexually differentiated, age-related, racialised and ethnicised identities. It has also become increasingly common for researchers to recognise the importance of studying family, intimacy and personal lives within a psychosocial frame. However, their narrative construction tends to be under-researched. While much sociological work on family lives has adopted an action or social constructivist frame of reference, it has tended to treat language as transparent, rather than as itself a constructed phenomenon.

Narrative approaches can, therefore, contribute valuable methodological elaborations and qualifications across disciplines. Moreover, and of great significance for narrative work, ‘family stories’ – oral, written, visual, crystallised in objects, archived and online – are forms of narrative with powerful historical, cultural and social currency (Smart, 2007). Such stories are themselves a major focus of narrative social research. However, they constitute a field about which there are no existing narrative methodological texts. This book will, therefore, provide an important contribution to this literature with reference to researching habitual practices in families’ everyday lives and how to conduct narrative research in this area.

Habitual practices are of central importance to everyday family life and identity construction in three ways.

First, the routinisation of habitual practices in families makes life easier: it takes for granted the scheduling of household tasks, caring responsibilities and other routines, saving effort spent in negotiation, and thus assisting with time compression and producing a ‘comfortable groove’ of order, repetition and coherence. Rita Felski draws on Agnes Heller's theorisation of everyday life to suggest that, ‘we would simply not be able to survive in the multiplicity of everyday demands and everyday activities if all of them required inventive thinking’ (Felski, 2002: 612).

Second, the importance of habitual practices to the construction of family identities is demonstrated by the readiness with which families claim habitual practices. More than three decades ago, Burgoyne and Clark (1984), for example, showed how ‘reconstituted families’ swiftly develop new narratives following divorce that are re-presented as entrenched, but which are relatively new in practice, including about how tasks are distributed and the gendered nature of staying at home to look after children. That this is consequential is illustrated by the (sometimes difficult) negotiations couples have to make about the ‘proper’ practices that should attend cultural celebrations such as Christmas (Mason and Muir, 2009). The establishing of such practices can also help individuals to position themselves within their families, for example, claiming identities as new mothers by demonstrating facility in particular cultural practices (Elliott et al., 2009). Narrative claims to everyday practices thus appear to be central to ‘identity projects’ (Giddens, 1991). These claims are rendered particularly complex by competing claims and identity projects within families, for example, across generations.

Third, family myths, scripts and legends (stories that are repeatedly retold in families) serve to maintain the family ethos and its idealised notion of itself (Byng-Hall, 1995; Samuel and Thompson, 1990). These are ‘families we live by’, which are often not the same as the ‘families we live with’ (Gillis, 2002). While family practices may appear personal, they are embedded in culture and history (Gross, 2005), in ways that mean the personal and social interpenetrate and are inextricably linked (Smart, 2007). Indeed, Morgan (1996) developed the concept of family practices to locate what families do and how they integrate beliefs with action, within (rather than separate from) other social practices. Here again, a narrative approach fits well with important currents in family research since narratives are both crucial to families’ meaning-making practices and the establishment of intimacy, and to the negotiation of everyday habitual practices. Families’ routinised practices provide a site for the analysis of the processes and constituents of identities; micro-social processes and the wider social structures in which they are located (Smith, 1987) and so for understanding social policy and practice issues.

However, methodologically, the study of habitual practices poses particular challenges. As Bourdieu (1979) observed, tastes and dispositions are often not conscious once they have become habitual; what is taken for granted as ‘natural’ is cultural, social and negotiated in context. Moreover, the minutiae of everyday lives are not readily recalled and observed by others because people deal routinely with them (Boddy and Smith, 2008). Repetitions of such practices serve to produce and reproduce identities though these can change over time. At particular times in the life c...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of figures and tables

- Author Biographies

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter 1 Family Lives, Everyday Practices and Narrative Research

- Chapter 2 Multi-Method Approaches in Narrative Family Research Across Majority and Minority Worlds

- Chapter 3 Secondary Analysis of Narrative Data

- Chapter 4 Carrying Out Narrative Analysis on Archival Data

- Chapter 5 Paradata in Marginalia: A Narrative Secondary Analysis

- Chapter 6 Researching Mothers’ Online Blog Narratives

- Chapter 7 Becoming Reflexive Doctoral Researchers: An Experiment in Collaborative Reflexivity Using a Narrative Approach

- Chapter 8 The Ethics of Data Reuse and Secondary Data Analysis in Narrative Inquiry

- Chapter 9 Narrative Research, Secondary Analysis and Family Lives

- References

- Index