- 216 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The ABC of CBT

About this book

The ABC of CBT introduces you to the basics of CBT, guiding you through how to apply the key principles, techniques and strategies across a range of disorders. Featuring case studies and worksheets, the book will support you to successfully incorporate CBT into your professional practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The ABC of CBT by Helen Kennerley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicina & Salud general. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 What is CBT?

The form of cognitive therapy described in this book is cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), a talking therapy pioneered by Dr A.T. Beck in Philadelphia in the 1970s.

CBT helps people manage problems by helping them change the way they think and behave, which in turn changes the way they feel. That's the goal of CBT, changing the way we feel, because feeling more confident, or less distressed, or less miserable is what makes the difference.

Beck's background was in neurology and psychodynamic psychotherapy, but in the 1960s and 1970s he drew on contemporary behaviour therapy and the emerging cognitive therapies in developing his own version of a cognitive-behavioural psychotherapy for depression. Treatment trials of CBT (e.g. Rush, Beck, Kovacs & Hollon, 1977) showed that it was an effective intervention for depression, and the first treatment manual, Cognitive Therapy of Depression, was published by Beck and his colleagues in 1979. This is still my go-to text, and if you haven't read it I would recommend that you do so. There is no better foundation for a practising CBT therapist because it captures the essence of Beckian CBT – practical guidelines combined with Beck's vision and philosophy. You might be interested to learn that the second chapter in the book focuses on the role of emotions in CBT and the third chapter is devoted to the therapeutic relationship. This immediately challenges the myths that CBT does not attend to feelings and that it disregards the therapeutic alliance.

There are also other myths about CBT that the book corrects, for example that CBT is a rather simple ‘cookbook’ approach to therapy – if a person has this problem then we use that technique. CBT is so much more than a mechanical application of techniques: it hinges on understanding a patient's problem, understanding CBT theory, and then bringing the two together in a formulation that is particular to that patient and will then guide therapy (see Chapter 5).

Another myth is that CBT is about positive thinking, but it's actually about developing a realistic outlook, keeping fears or misery or anger in proportion. And if there is a real problem to be addressed then the CBT shifts to problem-solving.

Beck's CBT rapidly developed as a successful intervention not only for depression but also for a range of anxiety disorders, anger problems, trauma-related problems, eating disorders, relationship difficulties and many other psychological and medical issues. It has stood the test of time by maintaining a very respectable research foundation. It was partly this compelling empirical support for CBT that led to it being central to the government's Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT: see www.iapt.nhs.uk) programme in 2008. IAPT has resulted in a year-on-year increase in the provision of CBT within the NHS in England and Wales with the aim of training over ten thousand therapists by 2021. The impact of IAPT has been rigorously evaluated and preliminary data from the pilot sites supported the effectiveness of the programme (Clark, 2018).

The CBT approach

The approach adopted in CBT is distinguished by a combination of characteristics that will be elaborated later in this text, but in order to set the scene here's a summary.

- The relationship between patient and therapist is collaborative: it's a working partnership.

- The therapy itself is overt, structured and active.

- Therapy is time-limited and (usually) brief.

- The approach of both therapist and patient is empirical.

- CBT is essentially problem-oriented.

A collection of basic principles also defines CBT. You'll see that several of them apply to other forms of psychological intervention, but it's the way that they are brought together that forms the foundation of modern CBT.

1. The cognitive principle

To illustrate a point when teaching, my former colleague, David Westbrook, would sometimes quote Hamlet in conversation with Rosencrantz: ‘there is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so.’ The point it illustrates is key to CBT, namely that emotional reactions are strongly influenced by cognitions. By cognition we mean thoughts, mental images, beliefs and interpretations – the meaning we make of our experiences.

This is illustrated by the simple example of two people losing their jobs.

The first person is miserable, and it is easy to assume that he's down because he has lost his job. This may be true – that the job loss caused depression. However, the second person is quite jolly so it can't be as simple as ‘job loss causes depression'. We need to find out what this particular life event meant to the individual.

The first man's thoughts were along the lines of: ‘This is terrible. I'm going to struggle to get another job at my age and I still have bills to pay.’ This would certainly make sense of his misery. In contrast, the second man felt relieved when he was fired because he'd been anguishing over what to do as he was unhappy at work. Now he had some compensation money to tide him over while he pursued something that suited him better, and he'd been spared the stress of making the decision to resign.

Now imagine another scenario: Anita is at a party where no-one immediately speaks to her. She could interpret this in many ways and she could experience different emotions:

- ‘I can't think of anything to say to anyone. I will look so boring and stupid.’ [This could lead to anxiety]

- ‘No surprise here. Nobody ever wants to talk to me, people just don't like me.’ [Which could have a depressing outcome]

- ‘People are so snooty. Who do these guests think they are?’ [A response that might trigger anger]

- ‘Typical party, everyone's got someone to chat with. I guess it's up to me to make the first move.’ [This reaction might even result in some anticipatory excitement]

Again we see that the meaning that we make of an event matters. This explains why not everyone is brought down by a relationship break-up or the diagnosis of an illness, just as not everyone is elated when they win a lottery or get a promotion. When two people react differently to an event it is because they are seeing it differently. The way they view it will affect their feelings and this in turn can influence their behaviour.

2. The behavioural principle

CBT also considers that what we do (our behaviour) can be crucial in maintaining or in changing our psychological states. Consider the above example again.

Anita's behaviour could have a significant effect on her thoughts and feelings. For example, if she approached another guest and chatted she might discover that the guest was friendly, and as a result she may be less inclined to think negatively about people in the future. On the other hand, if she withdrew and avoided joining the party she would not have a chance to find out if her thoughts were accurate or not, and her negative thoughts and feelings might persist. She might then be less inclined to accept the next social invitation.

Thus, CBT presumes that behaviour can have a strong impact on thoughts and emotions, and in particular that changing what a person does is often a powerful way of influencing thoughts and emotions.

3. The ‘interacting systems’ principle

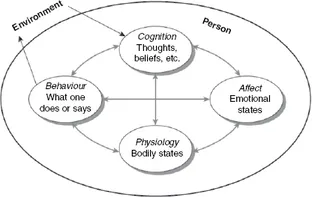

CBT goes beyond just considering the way we feel or think or behave, it takes the view that experiences are interactions between various ‘systems’ within the person and in their environment:

- Cognition.

- Affect or Emotion.

- Behaviour.

- Physiology.

These systems interact not only with each other but also with the environment (i.e. the physical, social, family, cultural and economic environment). Figure 1.1, based on Padesky and Mooney's five-system framework (Padesky & Mooney, 1990), illustrates the way in which the systems impact on each other so that change in one can affect the entire framework.

Figure 1.1 Interacting systems (Padesky & Mooney, 1990)

Source: 5-part model adapted with permission of the author, copyright 1986 by the Center for Cognitive Therapy; www.padesky.com

Hence a shift in cognitions can influence emotions, sensations or behaviour and vice versa, and in addition the individual impacts on the environment and vice versa. It is important that we take this dynamic feature into account when we assess a person's problems. If we don't grasp this interacting and bigger picture, then we risk missing something that could be crucial to understanding why a problem isn't going away. This will be explored more in Chapters 5 and 6 when we look at formulation and assessment.

4. The ‘working with what we see’ principle

The main focus of therapy for the CBT therapist is on what is happening in the present, and what the patient shares overtly. The main concerns are with the processes currently maintaining the problem and so we focus on these, trying to break unhelpful patterns of cognition and behaviour. Having said this, CBT does not dismiss the past – far from it. In developing an understanding of the origin of a problem we review historical factors and Chapters 5 and 6 explore this further. Nor does CBT dismiss processes that might not yet be fully conscious. We do consider factors that might be outside our patient's awareness, but rather than developing an interpretation that is shared, we build a hypothesis and then check out our therapeutic hunch with the patient, usually using Socratic methods (which we will review in Chapters 7 and 8).

5. The empirical principle

CBT believes we should evaluate our practice as rigorously as possible, using data rather than just clinical anecdo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Acknowledgements

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 What is CBT?

- 2 Developing a Working Alliance

- 3 Structuring Your CBT Session

- 4 Structuring a Course of CBT

- 5 Formulating Problems

- 6 Assessing Problems

- 7 Socratic Methods: Enquiry, Reflection and Logs

- 8 Socratic Methods: Behavioural Interventions

- 9Your Basic CBT ‘Toolkit’

- 10 Building on the Basics: Taking Things Forward

- Appendix

- References

- Index