eBook - ePub

Analysing Politics and Protest in Digital Popular Culture

A Multimodal Introduction

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Analysing Politics and Protest in Digital Popular Culture

A Multimodal Introduction

About this book

Supporting you with varied features throughout, this intriguing new book provides a foundational understanding of politics and protest before focusing on step-by-step instructions for carrying out analysis on your own.

It includes up to date cases, such as analysis of memes about Brexit, Trump and coronavirus, that cater for this quickly moving field.

It includes up to date cases, such as analysis of memes about Brexit, Trump and coronavirus, that cater for this quickly moving field.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Analysing Politics and Protest in Digital Popular Culture by Lyndon Way,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Communication Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Introduction Aims and Key Concepts

Chapter Objectives

- Introduce the aim of the book and the key concepts of politics and digital popular culture used throughout the book.

- Introduce issues surrounding relations between politics and digital popular culture.

- Introduce multimodal critical discourse studies and describe its advantages.

- Describe the contents of this book.

Key Concepts

- The aim of this book is to arm ourselves with an analytical toolkit that can reveal exactly how popular culture online is political.

- Politics is about ‘power’, ‘control’ and ‘status’ in society, governments, groups and organizations.

- Digital popular culture is popular culture that is (mostly) produced for and distributed online.

- A discursive perspective reveals not only what politics are articulated in (digital) popular culture, but also how these politics are expressed.

- Political ideologies are communicated in not only political speeches and news reports, but also entertainment (van Leeuwen, 1999; Machin and Richardson, 2012; Way, 2018a).

Introduction

At the time of writing, Donald Trump was the US president, Boris Johnson was the UK’s Prime Minister, Britain was leaving the European Union, the global climate crisis was at the fore of most political policy discussions, COVID-19 was causing carnage, while angry citizens in cities around the world were protesting racial injustice. As such, there was no shortage of newsworthy politics covered in mainstream news outlets. All the same, most of us did not rush to the television or news websites daily to hang on to the words of our politicians. Instead, most of us scrolled through our feeds, opened our apps, liked and composed posts, watched, added comments and shared videos, mash-ups, GIFs and comedy videos. Social media on our mobiles, tablets or other devices not only offer us our own personalized stream of entertainment, they also inform us on an endless parade of issues, events and people. This is political. The aim of this book is to arm ourselves with an analytical toolkit that can reveal exactly how this is political.

Since 1990 when the World Wide Web first rolled out to everyone who could afford it, scholars, the press and the public have opined and expressed their views on the social and political roles offered to us in our new digital world. Scholars from almost every discipline hold a wide range of positions from the wildly optimistic to the downright negative on exactly what these roles may be. Areas under examination include how it may democratize media control (Jenkins, 2009), act as the new fourth estate (Vatikiotis, 2014) and how it operates in social movements (Morozov, 2009), among a raft of other points of interest. Its inventor, Tim Berners-Lee, first envisioned the World Wide Web as ‘building a system for sharing data about physics experiments’ (Hern, 2019). Since these humble beginnings, the explosive rise of social media and Web 2.0 have seen digital media become an integral part of our lives, transforming how we inform, communicate and entertain, as well as change the ‘dynamic of discursive power’ (KhosraviNik, 2017: 583). Though many of these changes may be characterized as a plethora of misinformation, jokes about body fluids, commercialization and polarization of discourse, Berners-Lee still believes the World Wide Web should be ‘recognized as a human right and built for the public good’, ensuring and emphasizing ‘human rights, democracy, scientific fact and public safety’ (in Hern, 2019).

In this book, our concern is one part of this wider study of digital media. We focus on how we, as researchers, can examine relations between politics and popular culture in the digital. ‘Why are we focusing on this aspect of the digital?’ you may ask. Think about our own dealings with politics. Indeed, politics are expressed in the news, political party statements and how we vote. It runs through all aspects of our social life in terms of the ideas and values upon which we organize society and relate to each other. However, for most of us, the majority of this is done online. And yes, we may view ‘hard’ news and political commentary online, but studies show we prefer entertainment that communicates to us affectively as well as cognitively (boyd, 2008). Besides, ‘Political communication scholars are increasingly acknowledging that the historical separation of entertainment and news is obsolete’ (Esralew and Young, 2012: 338). Memes, parodies, music videos, cut and paste montages, caricatures, social television and online comments are an integral part of our daily political experiences, more so than most other political ones. It is here we encounter political issues, ideology and criticism, such as racism, minority rights, political tensions, populism, authoritarianism and environmental concerns. It is here we focus our study, where we most experience politics in everyday life.

In this book, we consider how to analyse the politics articulated in popular culture we experience on our phones, tablets, laptops and the like. As is the case with any area of scholarship, this can be approached from a range of perspectives, such as their effects or their social implications. I propose we approach this from a discursive perspective because it is here we can determine not only what politics are articulated in popular culture we experience digitally, but also how these politics are expressed. This book is a resource for students and scholars who want to discursively analyse politics in online communication. It offers a step-by-step guide on how to critically analyse politics in (digital) popular culture. Before we proceed, we need to define exactly what we mean by politics, popular culture, digital popular culture and a discursive approach. It is here we turn to now.

What is politics?

The Cambridge online dictionary defines politics as ‘the activities of the government, members of law-making organizations, or people who try to influence the way a country is governed’. Dictionaries also include definitions about ‘power’, ‘control’ and ‘status’ not only in governments, but within groups or organizations. On a societal level, there has been a shift in power where the ‘power of centralized nation states has waned’ with a corresponding rise in power of corporations and ‘the global economy’ (Machin and van Leeuwen, 2016: 246). There are also many other actors in society engaged in power, control and status. For example, some activists and those in the creative industries use popular culture to articulate a point of view, including the pleasures and values associated with it that may affect the actions and thoughts of fans. These acts and actors are political. Referring to popular music, Street (1988: 7) notes ‘Politics is not just about power. Nor is popular music. They are both about how we should act and think.’ In this book then, we include ‘the politics of the everyday … being concerned with issues of power, equality and personal identity … [that] affects the way people behave’ (Street, 1988: 3). Though much of the politics examined and analysed here involves governments and politicians, we also include politics of organizations and groups such as Extinction Rebellion, pro- and anti-Brexit groups, to name just a couple. So, memes, parodies and other popular culture experienced digitally about issues, events and politicians are considered as entertainment but also ‘the means of political and social deliberation’ (Denisova, 2019: 10).

What is (digital) popular culture?

Here we have three words, all contentious and all difficult to define. Let’s examine each concept, starting with ‘culture’. Arnold (1960: 6) claims culture, is ‘the best that has been thought and said in the world’. This includes literature by Shakespeare and music by Beethoven. However, we use the word ‘culture’ in more ways than just this. Raymond Williams (1963) agrees that culture is ‘intellectual, spiritual and aesthetic development’ of great philosophers, great artists and great poets. But he expands this definition to include documentary records, texts and practices of a culture (such as films and music recordings) and a particular way of life.

When we try to define popular culture, we need to consider how the term ‘popular’ works with our idea of culture (more of this in Chapter 2). This is not easy. As Bennett (1980: 18) notes, ‘the concept of popular culture is virtually useless, a melting pot of confused and contradictory meanings capable of misdirecting inquiry up any number of theoretical blind alleys’. It is usually defined in contrast to folk culture, mass culture, dominant culture, working-class culture, high culture and the like. Again, though there are whole books trying to define it, here we go back to Williams and his seminal work. According to Williams (1988: 236), popular means ‘widely favoured’ or ‘well-liked’. But it can also carry with it negative connotations of ‘inferior kinds of work’ and ‘a strong element of setting out to gain favour, with a sense of calculation’. So popular culture carries both positive and negative connotations which we hear in day-to-day conversations about it.

We put the word ‘digital’ in brackets a number of times in this book because we see ‘digital popular culture’ as a logical continuation of popular culture. That is, digital popular culture is very much a part of popular culture, though it also has its own affordances and these need to be taken into account (see Chapters 2 and 3). With this in mind, we can define digital popular culture as popular culture that is (mostly) produced for and distributed online. This includes still imagery, written posts, short animations, music videos, fan-sourced films, parodies, memes, Twitter mobs and social TV. It also includes excerpts from mainstream media found on our daily feeds. Digital popular culture is distinct from popular culture in ways other than its production and distribution. It also involves our engagement that includes, consuming, liking, sharing, commenting and altering. Digital popular culture emphasizes ‘participation’, ‘modification’ and ‘interaction’ as it develops and is shared online (Seargeant and Tagg, 2014: 4). This makes it unique and our approach to analysis needs to reflect this.

What are relations between politics and digital popular culture?

There is a lot written on relations between the digital and politics (see above and Chapter 2). Much of this focuses on social media and politics. Some scholars argue that social media provide ‘spaces of power for citizenry engagement, grass-root access, and use of symbolic resources’ (KhosraviNik, 2017: 583). It is argued that it is not just texts but also context of what we post, comment on and get posted to us that makes social media political (Pybus, 2019: 227). Our feeds are ‘cooked’ (Gitelman, 2013), producing value and ‘function as a power knowledge-relation and therefore, most importantly, it is inherently political’ (Pybus, 2019: 228).

This book is situated within these wider studies of the political roles of Web 2.0 and social media. These bigger issues are examined in great detail elsewhere and you may want to refer to some of the references in this book to gain a further understanding of some of the many studies examining aspects of this. Here, we focus on one aspect – that is, how to analyse the politics articulated in digital popular culture. We contextualize this book’s focus with an historical examination of relations between politics and popular culture in Chapter 2. Here, it is fair to say that relations between the two are complex, again with a wide range of opinions.

What is a discursive approach and why this approach?

Popular culture and politics can be examined in a number of ways, such as through the prism of popular cultural studies, socio-linguistics, cultural studies and sociology to name just a few. Most approaches ask what the relations are between popular culture and politics. This book considers not only what ideas digital popular culture can articulate about society, identities and events, but also how this is achieved using an innovative set of methods from multimodal critical discourse studies (MCDS). MCDS can provide answers to both ‘what’ and ‘how’ due to its attention to the details of how communication takes place, its interest in discourse and how ideologies are naturalized and legitimized. Let’s take a closer look at these ideas.

MCDS finds its roots in critical discourse analysis (CDA), an approach that examines linguistic choices to uncover broader discourses articulated in texts. By discourses, we mean ‘complex bundle[s] of simultaneous and sequential interrelated linguistic acts’, which are thematically interrelated (Wodak, 2001: 66). These discourses can be thought of as models of the world and project certain social values and ideas that contribute to the (re)production of social life. Some CDA scholars have pointed to the need to look more at how ideologies are communicated not only in political speeches and news reports, but also through entertainment (van Leeuwen, 1999; Machin and Richardson, 2012; Way, 2018a). These same scholars have also drawn on certain tools, approaches and assumptions in multimodality to show how discourses and ideologies, as in language, can be revealed by closer analysis of images, designs and other semiotic resources such as visual features, material objects, musical sounds and architecture. The approach in this book is part of this multimodal trajectory. Digital popular culture is a means of communication that articulates ideological discourses. It is through the modes of lexica (written, spoken and/or sung words), visuals and musical sounds that digital popular cultural commodities communicate ‘multimodally’.

MCDS is ideal for approaching digital popular culture. Producers of digital popular culture ‘draw on and mobilize complex multi-semioticity – combinations of specialized sets of linguistic features . . . discursive resources (such as genre, register, and style), pictures, moving image, sound and music, layout and composition’ (Leppanen et al., 2017: 8). Put more forcefully, ‘online linguistic performance and discourse genres cannot be fully understood without multimodal and interdisciplinary analytical frameworks’ (Calhoun, 2019: 28).

One approach that addresses some of the unique characteristics of communications in social media is KhosraviNik’s (2017) ‘Social media critical discourse studies (SM-CDS)’. Like the approach adapted in this book, KhosraviNik (2017: 584) emphasizes the need to consider both texts with context being upfront in the analysis. Like CDA, this approach calls for ‘a context dependent, critical analysis of communicative practices/content with a socio-political critique level’ (2017: 585). In this book, we analyse digital popular culture multimodality, acknowledging its uniqueness in constantly evolving contexts.

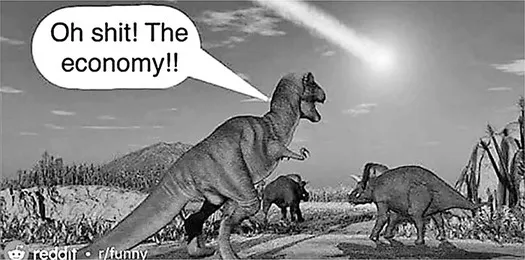

Let’s illustrate what we mean with an example. Figure 1.1 is a meme that a friend posted to my Facebook account during the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak of 2020. If we consider the meme out of context, we may find this funny due to the imagery and written words working together. It is funny that dinosaurs would know that the meteor crossing the sky will cause a major catastrophe. It is also funny that they are worried about the economy instead of their very existence. Even without the COVID-19 pandemic contextualization, this is a political statement about how many of us in society value economics over all else. However, this meme becomes not only funny but also more focused in its political critique if we know the political context. I showed this to my boy and he said it was not funny. When I gave him some context, he then ‘got it’. This encounter illustrates the importance of context.

Figure 1.1 2020 internet meme critiquing politicians’ reactions to COVID-19.

Source: u/JohnDonne on Reddit

Here is some context that makes this a pointedly critical meme at the time. This was sent to me while a number of national politicians around the globe were being criticized for their responses to the ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Illustration List

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1 Introduction Aims and Key Concepts

- 2 Politics In The Popular A Variety of Perspectives

- 3 Multimodal Critical Discourse Studies Why This Approach? How to Do It?

- 4 Analysing Online Comments Nationalism in Lexical Representations of Social Actors

- 5 Analysing Memes Authoritarianism in Visual Representations of Social Actors

- 6 Analysing Animations And Mash-Ups Brexit in Lexical and Visual Representations of Social Action

- 7 Analysing Music Videos Protest Against Politicians in Musical Sounds, the Representation of Place and Metaphors

- 8 Analysing Parodies Environmental Protest in the Recontextualization of Social Practices

- 9 Summary Of Our Approach And Findings

- References

- Index