eBook - ePub

Understanding Digital Societies

- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Understanding Digital Societies

About this book

Understanding Digital Societies provides a framework for understanding our changing, technologically shaped society and how sociology can help us make sense of it. You will be introduced to core sociological ideas and texts along with exciting global examples that shed light on how we can use sociology to understand the world around us. This innovative, new textbook:

- Provides unique insights into using theory to help explain the prevalence of digital objects in everyday interactions.

- Explores crucial relationships between humans, machines and emerging AI technologies.

- Discusses thought-provoking contemporary issues such as the uses and abuses of technologies in local and global communities.

Understanding Digital Societies is a must-read for students of digital sociology, sociology of media, digital media and society, and other related fields.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Section 1 Everyday life and the digital

Chapter 1 The digital sociological imagination

Contents

- 1 Introduction 23

- 1.1 Teaching aims 23

- 2 What is the sociological imagination? 24

- 2.1 Biography and history, troubles and issues 26

- 2.2 Reading The Sociological Imagination today 27

- 2.3 The sociological imagination and women’s cycling 28

- 3 Technological determinism and technological utopianism 33

- 3.1 Food banks and austerity 34

- 4 Technology implicated in the sociological imagination 36

- 5 The digital sociological imagination 39

- 6 Conclusion 41

- References 42

1 Introduction

How do the problems that we experience individually in everyday life compare with some of the broader issues happening around us in wider society?

This chapter introduces one of the main pieces of sociological theory you will be working with throughout the book. As described in the Introduction to the book, there are three main sociological threads that form the theoretical backbone of this book: individuals and society, people and things and power and inequality.

1.1 Teaching aims

The aims of this chapter are for you to:

- be introduced to the sociological imagination as a way of understanding individuals and society

- understand how technology figures in individual problems and broader society

- challenge notions that technology is new.

2 What is the sociological imagination?

The focus of this chapter is the sociological imagination, which is both the title of a book and an idea that outlines how individual problems relate to issues in broader society.

In 1959, C. Wright Mills wrote a book, The Sociological Imagination, to clarify his ideas on how social scientists could think about and frame sociology. In the first chapter of his book Mills describes the promise of sociology: how it can help everyone better observe and understand society. He describes how sociologists must pay attention to both ‘personal troubles’ and ‘public issues’. This chapter of the text book will unpack what Mills meant and how we can apply his ideas to digital societies, as well as to contemporary issues in society more broadly.

Mills begins his description of the sociological imagination by describing the problem facing ‘ordinary men’.

What ordinary men are directly aware of and what they try to do are bounded by the private orbits in which they live; their visions and their powers are limited to the close-up scenes of job, family, neighborhood; in other milieux [social settings in which decisions are made], they move vicariously and remain spectators. And the more aware they become, however vaguely, of ambitions and of threats which transcend their immediate locales, the more trapped they seem to feel.Underlying this sense of being trapped are seemingly impersonal changes in the very structure of continent-wide societies. The facts of contemporary history are also facts about the success and the failure of individual men and women. When a society is industrialized, a peasant becomes a worker; a feudal lord is liquidated or becomes a businessman. When classes rise or fall, a man is employed or unemployed; when the rate of investment goes up or down, a man takes new heart or goes broke. When wars happen, an insurance salesman becomes a rocket launcher; a store clerk, a radar man; a wife lives alone; a child grows up without a father. Neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.(Mills, 2000, p. 3)

What is Mills describing here? He’s talking about individuals and their daily life. When life is stable for an ‘ordinary individual’, that person rarely looks beyond the immediate circumstances of their career, their family or where they live. However, Mills suggests that society impacts individual lives more than the ordinary person realises. Changes in society impact individuals. The examples that he gives talk primarily about economic shifts from a society becoming industrialised, but he also discusses temporary societal shifts such as war, and how they impact individuals and families.

Who was C. Wright Mills?

Figure 1.1 American sociologist Charles Wright Mills pictured towards the end of his life in 1960.

Charles Wright Mills (1916–1962) was an American sociologist who produced the bulk of his work in the mid 20th century. His writing focused on the roles of governments, military and bureaucracy and their collective impact on inequality in society. Mills completed his PhD studies on the sociology of knowledge before the start of World War II.

Post World War II, Mills’s writing focused on developing critical standpoints on social inequality, problems facing the middle class, and power held by the elite. Crucially, he often disagreed with sociologists of the same era and asserted that they were often too detached from the communities they claimed to study. He called for sociologists to be more concerned and involved with problems in everyday life, with the intention that sociologists should be activists, as well as researchers.

His most famous work is The Sociological Imagination, which is the focus of this chapter. The Sociological Imagination was written in 1959 and was intended to provide a way for people to observe and think about the relationship between individual experiences and world events or troubles.

Mills describes a framework for helping us, as social scientists, understand and observe how individuals relate to society. Although he wrote this text in the mid 20th century and uses some language and examples that might sound a bit outdated, are you able to identify examples of personal troubles and public issues?

The concept of the sociological imagination is helpful for when we ask questions about what is happening in digital societies and to whom.

2.1 Biography and history, troubles and issues

Mills sometimes describes his ideas with interchangeable terms. Instead of talking about ‘public issues’ he may refer to ‘history’. And other times, when talking about ‘personal troubles’, he may use the term ‘biography’. It may be more helpful for you to consider the sociological imagination in terms of personal ‘biography’ and a public ‘history’.

Mills defines troubles and issues thus:

Troubles occur within the character of the individual and within the range of his immediate relations with others; they have to do with his self and with those limited areas of social life of which he is directly and personally aware …Issues have to do with matters that transcend these local environments of the individual and the range of his inner life. They have to do with the organization of many such milieux into the institutions of an historical society as a whole, with the ways in which various milieux overlap and interpenetrate to form the larger structure of social and historical life. An issue is a public matter: some value cherished by publics is felt to be threatened …… consider unemployment. When, in a city of 100,000, only one man is unemployed, that is his personal trouble, and for its relief we properly look to the character of the man, his skills, and his immediate opportunities. But when in a nation of 50 million employees, 15 million men are unemployed, that is an issue, and we may not hope to find its solution within the range of opportunities open to any one individual.(Mills, 2000, pp. 8–9)

2.2 Reading The Sociological Imagination today

Some of the texts that you will read in Understanding digital societies were written during a time where it was more the norm to use phrases or terms that we might find offensive nowadays. C. Wright Mills’s writing has quite a specific tone that is representative of a certain period. Sociological writing from the early to mid 20th century can sometimes be difficult to navigate as the reader is often assumed to be of a certain class, gender or education level. When The Sociological Imagination was written in 1959, far more men of middle and upper class backgrounds had access to higher education in comparison to women or those in the working class. This is reflected in the text, as Mills describes the sociological imagination with examples that seem to be rather masculine: they refer to an era where men were expected to be the breadwinners for the household. This approach might seem out of touch with contemporary living if you are part of a living situation where there are two or more incomes providing for the needs of the household. Although the examples that Mills and others sociologists of that era use to illuminate their ideas may seem outdated, the ideas themselves remain valuable in helping us examine the world around us. When reading these older sociological texts you should consider how their ideas could be used or challenged within the contemporary context.

Mills’s description of the sociological imagination can be helpful when we examine what is happening in contemporary society. Mills describes the relations between history and biography, along with the relations between personal troubles and public issues. Essentially, Mills’s sociological imagination shows us that problems we encounter individually can often be understood as contributing to the narrative of broader problems happening in society.

2.3 The sociological imagination and women’s cycling

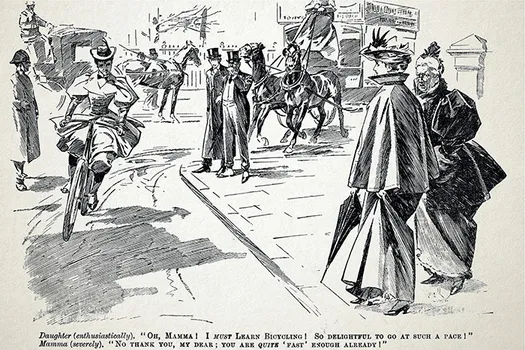

Figure 1.2 This cartoon from the late 1890s shows how it was considered controversial for women to be seen cycling in public.

One example of the relationship between individuals and society can be found in Kat Jungnickel’s book Bikes and Bloomers (2018), where she investigates the difficulties faced by upper and middle class women in 1890s Britain who wished to take up cycling. In her qualitative research Jungnickel describes the biographies of women who took up cycling. Using archive material such as newspaper and magazine articles, patents and birth, death and marriage registrations, she found out that women cycling along the streets of suburban Victorian London in the 1890s faced extreme danger due to the fact that women’s clothing often got caught in the bicycle’s moving parts. They also faced abuse on the street by pedestrians and passers-by that believed women of that social standing should not take part in such physical activity (Figure...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Section 1 Everyday life and the digital

- Chapter 1 The digital sociological imagination

- Chapter 2 The presentation of self in digital spaces

- Section 2 Society, technology, citizens and cities

- Chapter 3 Planning the cities of the future

- Chapter 4 Migration, diaspora and transnationalism in the digital age

- Chapter 5 Transnational digital networks: families and religion

- Section 3 Humans and machines

- Chapter 6 Semi-autonomous digital objects: between humans and machines

- Chapter 7 Freedom, fetishes and cyborgs

- Chapter 8 Health and digital technologies: the case of walking and cycling

- Section 4 Uses and abuses of the digital

- Chapter 9 Material digital technologies

- Chapter 10 Disinformation, ‘fake news’ and conspiracies

- Chapter 11 Cybersecurity, digital failure and social harm

- Chapter 12 Too much, too young? Social media, moral panics and young people’s mental health

- Chapter 13 Algorithms

- Glossary

- Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Understanding Digital Societies by Jessamy Perriam, Simon Carter, Jessamy Perriam,Simon Carter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Media Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.