- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hidden History of Downtown St. Louis

About this book

A reputation as the town of shoes, booze and blues persists in St. Louis. But a fascinating history waits just beneath the surface in the heart of the city, like the labyrinth of natural limestone caves where Anheuser-Busch got its start. One of the city's Garment District shoe factories was the workplace of a young Tennessee Williams, referenced in his first Broadway play, The Glass Menagerie. Downtown's vibrant African American community was the source and subject of such folk-blues classics as "Frankie and Johnny" and "Stagger Lee," not to mention W.C. Handy's classic "St. Louis Blues." Navigate this hidden heritage of downtown St. Louis with author Maureen Kavanaugh.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hidden History of Downtown St. Louis by Maureen O'Connor Kavanaugh, Thomas P. Kavanaugh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

THE MOUND CITY

Sometime between the years AD 1050 and 1400, an amazing culture with deep roots in Louisiana—and, later, the Ohio and Tennessee River Valleys—reached its zenith on the fertile, alluvial floodplain of the mid–Mississippi River Valley, at the present site of Cahokia Mounds,1 Illinois, across the river just north and east of downtown St. Louis. Sometime during that same period, its people also constructed a mounded, sister city above the labyrinth of caves on this, the west bank of the Mississippi, that would give St. Louis an early nickname, the “Mound City.”

These people—who came to be known as Mississippians for the great river along which they raised thousands of earthen mounds from the Gulf of Mexico to the Great Lakes—built the largest pre-Colombian earthwork in the Americas. It was a huge, truncated pyramid, rectangular in shape2 and approximately one thousand feet long and seven hundred feet wide, rising in four terraces to a height of one hundred feet. A platform mound with a wooden temple at its summit overlooked the ceremonial plaza of their capital and the first city north of Mexico.3

Today Monk’s Mound is preserved with roughly another 79 of the possible 109 to 120 earthworks that once covered a six-mile area centered at the Cahokia Mounds site (later named for an Illini tribal nation residing in the area). Time and weather have altered the original sizes and caused the once sharply delineated edges of many to slump, but a remarkable number survive as reminders of the people who ruled the Mississippian kingdom from the mid–Mississippi River Valley for several hundred years.

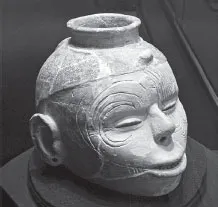

Effigy Pot of the Mississippian Culture. Courtesy of the photographer, Herb Roe, and the Hampson Archaeological Museum State Park, Wilson, Arkansas.

What we know of the Mississippians comes primarily from the decadeslong archaeological work carried on at Cahokia Mounds, Illinois, and from much broader excavation and research in the area of the lower Mississippi River and its tributaries.

Mississippians buried their royal dead in aboveground earthen mounds that were often conical in shape. They constructed platform mounds leveled at the top for the homes of their chieftains and still higher temple mounds. At Cahokia, they also built wooden enclosures for defense and wood henges to mark the movement of the sun.4

Although their language is lost to us, and no evidence of a written language has been found, artistic symbols that illustrate a reverence for the sun and other elements of nature survive. At the height of their culture, they were an agrarian people who harvested enormous quantities of corn, beans and squash. There is also evidence to suggest that they practiced human sacrifice.

These Mississippians hunted game and fished the rivers along which they settled, trading with other Native Americans over a vast area—from the Great Lakes in the North to the Gulf of Mexico in the South and from the Appalachian Mountains in the East to the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains in the West.

During the Medieval Warm Period (MWP), they moved into the mid–Mississippi River Valley and perfected a method of clay construction distinguished by the use of ground mussel shells to produce thinly shaped walls that were watertight. Among their artisans were highly skilled metalworkers who sculpted and incised images of them and their spirit gods onto jewelry even as their potters did in clay. These Mississippians were the first known architects of the Greater St. Louis landscape.

In 1673, Jesuit missionary Jacques Marquette and explorer Louis Joliet drew a map of the upper Mississippi River where it intersects the Grand River, identifying numerous tribal people whom they encountered on their banks. On this map they sketched several earthen mounds that they observed along the rivers.

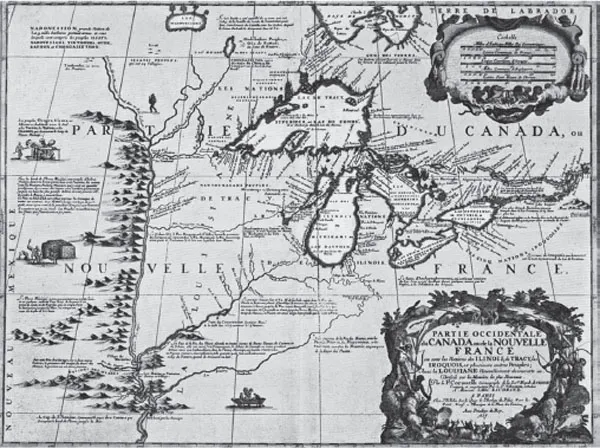

But it’s Vincenzo Coronelli’s 1688 Map of Western New France, including the Illinois Country that illustrates how St. Louis gained the early nickname of Mound City. If you follow the line of the Mississippi south to near the bottom of Coronelli’s map, you will see just below its confluence with the Missouri River a widened area of mounds that encircle the river. They are but a suggestion of the more than one hundred man-made, mountain- and hill-like structures that dotted this area.

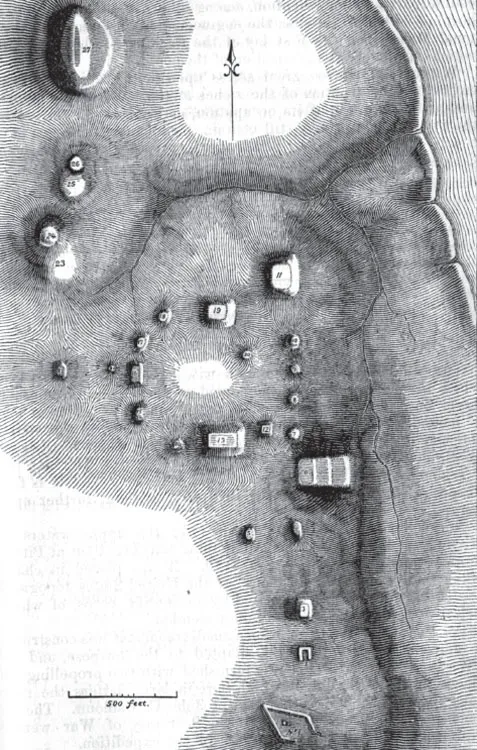

There is no record of the French and Creole founders of St. Louis disturbing or leveling the earthworks on the west bank of the river, but later settlers would build on them and eventually demolish all but Sugar Loaf Mound, south of downtown St. Louis. Had it not been for a happy accident of fate, there would be no visual record or scientific survey of the “Ancient Mounds at St. Louis, Missouri,” as T.R. (Titian Ramsey) Peale, chief examiner of the United States Patent Office, named them when he published the map he had made with Thomas Say in 1819.5

Peale and Say were young officers on an exploratory expedition under the command of Major Stephen Long of the U.S. Topographical Engineers, headed for the upper Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, when their steamer, the Western Engineer, had an accident; they needed to return to St. Louis for repairs. The “ancient mounds just above the town” captured their interest, and with time on their hands, Titian Peale and Thomas Say surveyed the St. Louis Mound Group shown. Within about fifty years, all of them would be erased from the St. Louis landscape.

Map of Western New France, including the Illinois Country, by Vincenzo Coronelli, published in 1688. From the National Archives in Canada.

In 1861, Peale came upon his beautifully drawn map in an old portfolio and offered it to the Smithsonian, which promptly published it along with the measurements and description of twenty-seven structures. Numbered from 1 through 27, they represent the remains of the bastion of St. Louis’s old Spanish stockade and all or parts of twenty-six mounds: shape, height, length of longitudinal and transverse bases, distance from one to another and, in the case of Mound 2, distance from the bastion of the Spanish stockade.6

They also indicated the distance of the mounds from the edge of the bluff, all of them having been constructed on the second terrace facing the Mississippi, and numerous mounds directly across the river, as well as Cahokia to the northeast. The bases of the mounds ranged in shape from squares to oblong squares, nearly square, irregular, parallelogramic, quadrangular and elongated-oval, with tops that were conical, convex or flattened. There were also two small barrows. Some bases were as short as 25 feet, while the longest was 319 feet. They ranged in height from 4 feet to approximately 34 feet. Two of these mounds were especially distinctive: Mound 6 for its shape and Mound 27 for its size.

Mound 6, a three-tiered parallelogram, was in colonial times perhaps the most picturesque of the St. Louis Mounds, for the French called it Falling Garden. In spring, summer and autumn, wildflowers and blooming vines would have cascaded down its steep, obliquely sculpted slope.

The earliest St. Louisans did not dislodge these mounds, but they did name them and used them as boundaries, and as landmarks, to gauge their relation from the river to the bluffs and the town, as would later steamboat pilots—the Mississippi River, with its circuitous bends and rough shoals, could be treacherous to navigate.

La Grange de Terre (the Barn of Earth) was, at approximately thirty-four feet, the second-tallest Mississippian Mound in this area, although it stood distant from its neighbors. Thomas Say described it in 1819 as “an elongated-oval form, with a large step on its eastern side…1,463 feet north of Mound 26.”

During the nineteenth century, artists Maria von Phul and John Casper Wild made paintings of Mound 27, and photographer Thomas Easterly later produced a series of daguerreotypes recording its demolition. But T.R. Peale’s map remains the only known image of the entire downtown St. Louis Mound Group.

The Ancient Mounds at St. Louis in 1819, by T.R. Peale and Thomas Say. From the 1861 Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution, page 387.

Just one year earlier, in 1818, Kentuckian Maria von Phul, an enterprising and adventurous young painter visiting family in St. Louis, rendered in watercolor what English-speaking St. Louisans called the “Big Mound.” It reveals that bushes and small trees had taken root in the earthwork along with prairie grasses. She then climbed La Grange de Terre and painted the view from the top—the Mississippi River below and earthen mounds on its eastern bank.

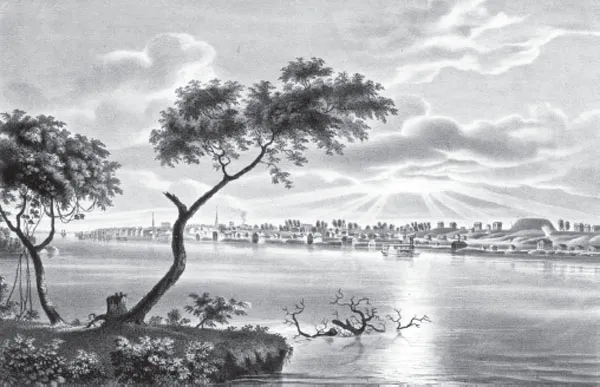

J.C. Wild was a Swiss artist who came to the United States in 1832 and made a remarkable record of the Mississippi Valley in paintings and colored lithographs. His 1840 Northeast View of St. Louis from the Illinois Shore shows the scale of the Big Mound in comparison to the buildings around it. Wild clearly positioned himself far enough away from the mound to give a clear perspective of its relation to the Mississippi River and the bluff on which it stood. His painting illustrates what a remarkable landmark it was.

Today, a boulder with an engraved plate situated in a newly created park at North Broadway and Mound Street, in proximity to the Stan Musial Veterans’ Memorial Bridge, marks the approximate site of the Big Mound.

Thomas Easterly’s daguerreotype of the Big Mound, shortly before it was completely demolished for construction of a railroad line in 1869, shows the tremendous scale of the earthwork in proportion to the people standing on and around it. But at a mere thirty-four feet, it would have been dwarfed by its predecessor, Cahokia’s ten-story-high Monk’s Mound.

Archaeological excavation at the time of the Big Mound’s demise revealed that it contained four separate strata of soil and that its height had been increased over time. The large burial chamber at its base, which had collapsed, housed the skeletal remains of several individuals, who were buried facing west, along with river mussel shells, seashells from the Gulf of Mexico and copper ornaments.7 Archaeologists believe that during the Mississippian era, Monk’s Mound in Cahokia would have been visible from the Big Mound in St. Louis and that fires burning from their summits would have allowed for smoke signals to carry messages over a distance of several miles.

What became the expanded city of St. Louis contained many more Mississippian earthworks, some of them very large, mostly constructed in proximity to the river but some more than a mile distant from its banks. All of those mounds were demolished or significantly altered except for Sugar Loaf Mound south of downtown. The top was leveled and modest homes built on the summit and second step during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and a landfill conceals its southern base. This sweeping, three-step structure, which originally ended in a conical mound with a steep southern slope, is a striking example of Mississippian architecture and craftsmanship.

Northeast View of St. Louis from the Illinois Shore, by John Casper Wild, 1840. From the J.C. Wild Lithographs Collection. Missouri History Museum, St. Louis.

Dated to about AD 1000, Sugar Loaf Mound is the last known vestige of the Mound City, the sole extant work of the first known architects of the St. Louis landscape. Like the ancient mounds that survived in the northern part of downtown St. Louis into the early nineteenth century, it was constructed over a cave, an entry to a spiritual underworld.

Sugar Loaf (Pain de Sucre to the French) has never been completely excavated and likely won’t be. The Osage Nation, which now owns it, regards Sugar Loaf as an ancestral burial site. When St. Louis was founded, the Osage were one of the most powerful tribal nations in the mid–Mississippi Valley. Their descendants are planning to restore it as a heritage and interpretive site.

Although graded very differently, Sugar Loaf is a three-step mound, as was Falling Garden. A fascinating thirty-minute documentary, Uncovering Ancient St. Louis, written and produced by Mark Leach in 2009, describes recent archaeological and geological research being done into Mississippian Culture on this, the west side of the river.8 In it, archaeologists suggest that such three-tiered mounds may have related to a Mississippian cosmology that encompassed a three-tiered world—underworld of caves, middle world of earth and water and sky world into which tall mounds reached. They also pose a theory that ancient St. Louis, honeycombed as it was with caves, was an ideal site over which to erect mounds, possibly a “sacred sister city of the moon in the west, corresponding to Cahokia, sacred city of the sun in the east.”9

A Journal of American Science, published in 1882, reported that French explorers had found two human footprints on the downtown St. Louis riverfront “made into rock when the earth was still soft.” In 1763, while scouting out a location for a trading post, St. Louis founder Pierre Laclede and co-founder, Laclede’s young stepson, Auguste Chouteau, noticed those ancient footprints.

Directly below the downtown St. Louis Mound Group, Mississippians sculpted terraces out of the limestone bluff and created a stairway that led from the edge of the river up to the mound complex, suggesting a place of powerful ritualistic ceremony and significance. But it appears that sometime between 1350 and 1400, Cahokia and its sister city at presentday St. Louis were abandoned. Precisely what became of the Mississippian Mound People is unknown. The Late Mississippian Era (circa 1450–1540) was a time of growing political conflict and warfare, within and between neighboring ch...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction. Forward (and Backward)

- 1. The Mound City

- 2. Early Missouri Tribes and First Nations

- 3. Enlightened Frenchman in the Heart of Ancient America

- 4. Colonial St. Louis (La Poste de Saint Louis)

- 5. The Battle of St. Louis (L’Année du Grand Coup

- 6. Gateway to the West

- 7. Frontier Capital

- 8. Brick City

- 9. A House Divided

- 10. Great River Metropolis

- 11. The Fourth City and Epicenter of Ragtime

- 12. Bicentennial St. Louis

- 13. The River, the Arch, the City and Its Caves

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author