- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Dams of Western San Diego County

About this book

The unreliability of the San Diego River compelled the Franciscan fathers to construct the area's first dam in 1813 to conserve drinking and irrigation water for the Mission San Diego de Alcalá. This water-driven circumstance continued and expanded in the ensuing American era. Lacking a reliable water source at the turn of the 20th century, San Diego County was destined to experience modest growth. The region's semiarid conditions, cyclical droughts, and existing river systems determined that the only effective way to maintain a ready water supply was to conserve runoff and river floodwaters behind dam-created reservoirs. Between 1888 and 1934, private and municipal interests constructed a series of massive structures that made San Diego County the dam-building center of the world. The county featured some of America's first multiple arch dams and earliest hydraulic fill dams. Into the mid-1940s, dammed reservoirs remained the principle water source for county consumers and made the municipal expansion of the city of San Diego possible.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Dams of Western San Diego County by John Martin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Architecture General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

THE DAMS OF WESTERN

SAN DIEGO COUNTY

SAN DIEGO COUNTY

San Diego city hydraulic engineer Hiram Savage produced this map of the county’s water resources at the request of the common council in 1921. Aside from El Capitan Dam, built in 1934, by this time, either private or municipal interests had constructed the county’s major dams. Those dams included Sweetwater, Lower Otay, Barrett, Morena, Hodges, Henshaw, Wohlford, and Murray. (SDCL.)

The Los Padres Dam or Old Mission Dam was both the first significant man-made water feature in the region and the first on the San Diego River. The dam also has the distinction of supplying water for the earliest major irrigation project on the Pacific coast. Locally, Mission Dam was the predecessor to all subsequent conservation dams in San Diego County. (Courtesy of Gary Van Velser.)

In 1803, the Franciscans at Mission San Diego started construction on a dam to create a water source to irrigate fields, water livestock, and provide domestic water. Relying on Indian labor, the fathers completed the dam in 1814. The cobblestone, brick, and concrete structure, located in a gorge about six miles to the northeast, transported water to the mission via a ceramic tile–lined aqueduct. (SDCL.)

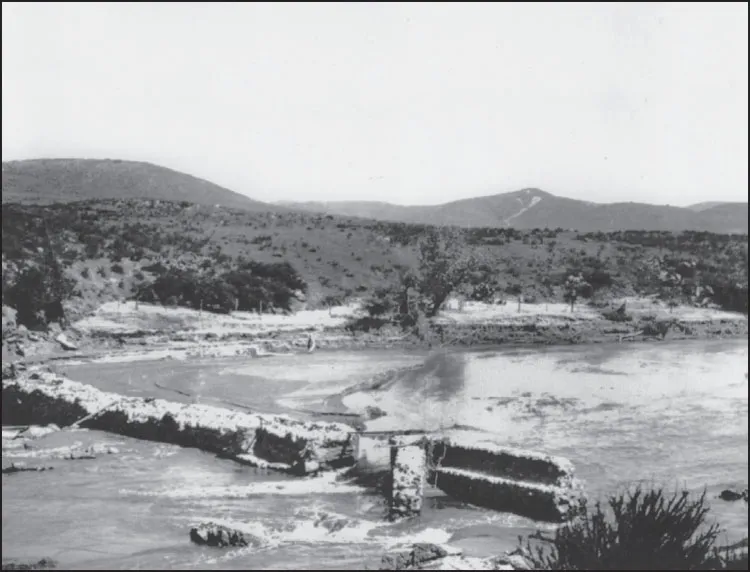

The Mission Dam, shown here in 1917, formed a small reservoir that the mission fathers hoped would provide a water source in dry years. However, the pond, called Collins Lake or Kumeyaay Lake, was so small it dried up during a drought or when the San Diego River ceased to flow. It was over 70 years before the next major dam project in the county. (SDCL.)

Mission Dam’s usefulness diminished after the Mexican government secularized the mission and expelled the Franciscans in the 1830s. There was no motivation to repair the structure, and the dam fell into disrepair. Town leaders approved repairs to the dam in 1874, and it was briefly in use. Since 1968, the dam has been protected within the Mission Trails Regional Park as a California historical landmark. (Courtesy of Garry Van Velser.)

After the Mission Dam, a diverting dam on the San Diego River was the next major structure to appear in the county. In 1885, Theodore Van Dyke filed a claim for water on the San Diego River and organized the San Diego Flume Company. His plan was to take water from the Cuyamaca Mountains and the upper San Diego River and deliver it to the city through a flume system. Engineer John D. Schuyler designed a dam to divert the natural flow of the San Diego River and create a reservoir that could store around 7,000 acre-feet of water to feed the flume. Van Dyke’s idea was to keep the reservoir at peak capacity and allow any excess water to flow downstream. The flume owners expended $54,400 on the original structure, which was functional, if leaky. (Both, SDCL.)

Flume officials never bestowed a formal name on the structure; it was simply known as the diverting dam. The flume engineers chose a location just below the confluence of the southward-coursing San Diego River and the outfall of Boulder Creek, where it departed a wooded valley 18 miles below Cuyamaca Lake. Water was released directly into the flume system through a manually operated gate at the base of the east end of the dam. At 810 feet in elevation, the water gravity-flowed out of the 35-foot dam through the flume to the town of Lakeside and on to a catch site before being relayed to the city distribution system. (Both, courtesy of Helix Water District.)

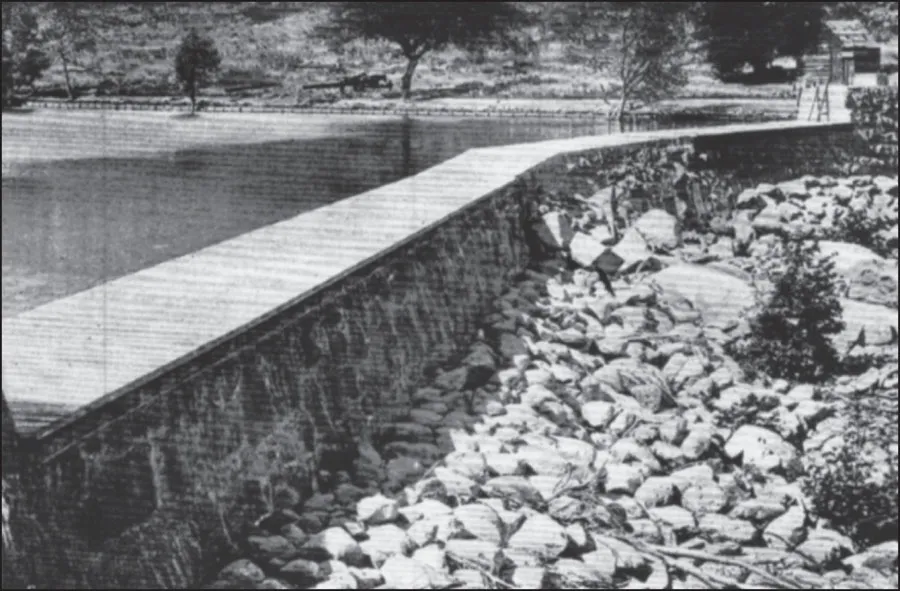

The original dam, shown in this 1897 photograph, was a 540-foot-long stone and masonry earth-filled dam with a simple overflow channel spillway on the west end and overflow points near the middle of the flat crest. After completing the dam and testing its integrity, the engineers decided to strip off the original rip-rap face and apply a smoother concrete and masonry layer. (SDCL.)

For Van Dyke’s flume system to be successful, it required more water than the seasonally flowing San Diego River could supply. To supplement the supply, he planned to build a reservoir in the surrounding Cuyamaca Mountains, which received an annual rainfall of 36 inches. Van Dyke sold the idea to a group of British stockholders, and the San Diego Flume Company became reality. (SDCWHA.)

In 1888, Van Dyke purchased a site at a natural pond at the headwaters of Boulder Creek, an eastern tributary on the upper San Diego River, for $54,000. The British consortium funded the construction of Cuyamaca Dam there that September. The timing of the enterprise was unfortunate, as a 10-year drought descended on San Diego from 1895 to 1905 and the river and the reservoir dried up. (SDCWHA.)

Cuyamaca was originally to be a masonry dam, but the lack of a quarry necessitated constructing a low, earth-filled structure. Completed in February 1887, the low sloping dam stood 35 feet in height and 635 feet in length, with a 10-foot-wide crest. The flume owners called the area Cuyamaca, but the Indians called it Laguna Que Se Seca—the lake that dries up—for reasons the flume owners soon discovered. (SDWHA.)

The flume was an engineering feat. The water released from the diverting dam poured into a redwood chute that transported it over 30 miles downstream. Roughly paralleling the San Diego River, the open wooden trough carried the water over raised sections, through tunnels, and across high wooden trestles, with distribution points for the backcountry ranches and farms along the river valley. The flume was a remarkably leaky structure, and drought and the problematic nature of the upstream water source rendered the system unreliable. However, despite debris and dead animals clogging the flow, and the recreation value for ranchers’ kids, the flume was in service until the 1940s. The flume’s final destination was Eucalyptus Reservoir on Grossmont Knoll. (Both, SDCHWA.)

Eucalyptus Dam and Reservoir, located near Grossmont Heights, was the flume’s termination point. The 34-foot-high, 275-foot-long dam that conserved the water was apparentl...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Dams of Western San Diego County

- 2. The Dams That Never Happened

- 3. The Men Who Built the Dams

- 4. Spectators, Guests, and Visitors

- Index