- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Civil Rights in Birmingham

About this book

Since the city?s founding in 1871, African American citizens of Birmingham have organized for equal access to justice and public accommodations. However, when thousands of young people took to the streets of Birmingham in the spring of 1963, their protest finally broke the back of segregation, bringing local leadership to its knees. While their parents could not risk loss of jobs or life, local youth agreed to bear the brunt of resistance by law enforcement and vigilantes to their acts of civil disobedience. By the fall, even youth who did not participate in the Children?s Movement gave all for the struggle when a bomb placed in the 16th Street Baptist Church exploded and killed four girls.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Civil Rights in Birmingham by Laura Caldell Anderson,Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

BARRIERS

BLACK AND WHITE—

ONE CITY, TWO WORLDS

ONE CITY, TWO WORLDS

Segregated streetcar seating, as pictured here, is but one example of a public accommodation to which African American citizens were given unequal access. “Colored passengers” were typically required to pay the drivers of buses and streetcars in the front of the vehicle, exit, and then re-enter the vehicle via a side or back entrance. Seating was in the back. No matter how inclement the weather, African American passengers were subject to this treatment, yet they paid the same fare as other passengers. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

The city of Birmingham and its industries were built on the backs of thousands of African American laborers who migrated to the city to toil in its mines and mills. The exploitation of black labor was most harsh in the convict labor system, outlawed in 1928. Men convicted of minor and vague offenses such as “vagrancy” were leased to mines and mills by local and state governments and forced to endure harsh living and working conditions in labor camps, such as the one pictured here. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

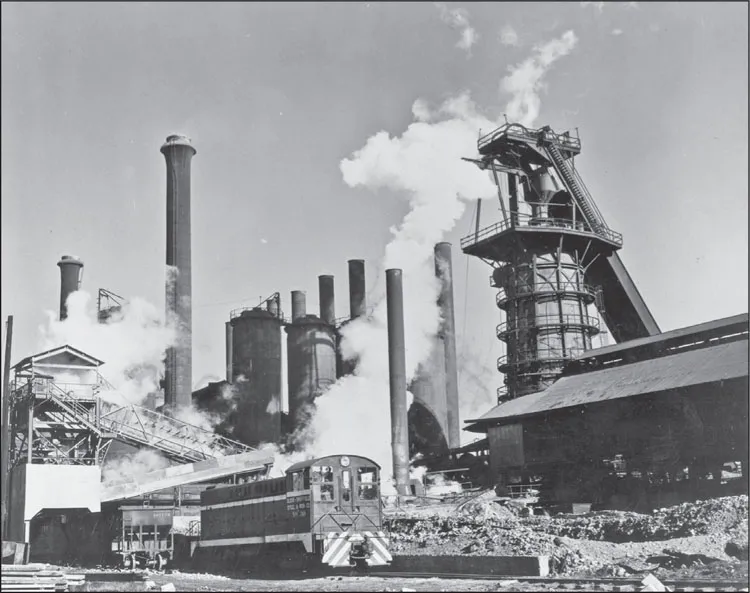

Sloss Furnaces, located near downtown Birmingham, produced pig iron. Management and engineering jobs were for white men only. At the bottom of the employment hierarchy were African American men, who held only “helper” jobs such as stove tender and assistant to carpenters and other skilled workers. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

The city of Birmingham was founded in Jones Valley in 1871 after entrepreneurs came together to extract minerals needed to produce iron. All the ingredients lay in deposits within a 30-mile radius of the new city: seams of iron ore and abundant coal, limestone, and dolomite. The majority of laborers were African American, and wages were the lowest in the nation. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

Alabama was a major iron and steel producer because the requisite ingredients were in close geographical proximity to one another and labor was cheap and plentiful. The most successful companies controlled all of the facilities and tools associated with production, from extraction to manufacture. Pictured here are laborers in one mine involved in various aspects of the work. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

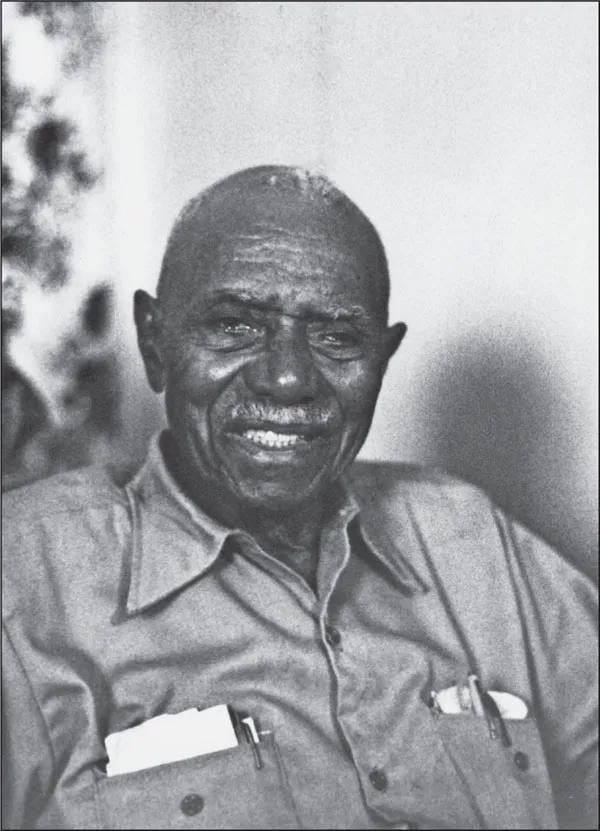

Born in 1898, sharecropper, steelworker, and communist Hosea Hudson organized Birmingham miners and mill workers. Instrumental in founding the first unions in the area, he served as president of Steel Local 2815 and was a delegate to the Birmingham Industrial Union Council. Although he lost his jobs and union positions locally due to his activism and politics, Hudson remained a tireless fighter for workers’ rights until his death in 1988.

African American culture was anchored by the church. Hundreds of churches, of all sizes and representing many denominations, were located throughout the city. Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, seen here, was designed by Wallace Rayfield and constructed in 1911. The congregation itself was founded in 1873 as the first church for African Americans in the city. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

The children’s Sunday school choir of Bethel Baptist Church of Collegeville is pictured here on the steps of its original building. Established in 1904, Bethel Baptist was later pastored by Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth, leader of the Birmingham movement. The building was damaged by three separate bombings over the years. The working-class neighborhood of Collegeville is located north of downtown Birmingham. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

Segregation laws and customs were enforced on the playing fields, too. The Birmingham Black Barons, pictured here, were Negro American League champions in 1943, 1944, and 1948. Willie Mays and Lorenzo “Piper” Davis were two of the team’s best-known players, and the Black Barons had fans on both sides of the color line. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

Founded in 1889, Birmingham’s Sojourner Truth Club was one of the nation’s oldest federated colored women’s clubs. Its motto was “lifting as we climb.” (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

The Cosmos Club, pictured here in 1916, organized socially in order to exert a constructive influence on the larger African American community. The club was but one of several women’s clubs dedicated to the social and cultural welfare of its members and to working in service to others. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

Birmingham educator and columnist Geraldine Moore described the city’s large number of social and service clubs as having “specific objectives—thrift, art appreciation, community improvement, elevation of the cultural standards of the people, recognition of special talent or worth on the part of individuals—these are a few that are typical. Thus it is that each club wields its own influence.”

Rev. William Reuben Pettiford organized the Penny Savings Bank in Birmingham in 1890. The bank was the first black-owned and -operated financial institution in Alabama. Created as a necessity of de facto and, later, codified segregation, the bank backed and encouraged development of black businesses until its closing in 1915. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

Born in 1870, beloved educator Arthur Harold Parker was founder and first principal of Industrial High School, where he served until his retirement in 1939. Upon his retirement, the school was renamed A.H. Parker High School. (Courtesy Birmingham Public Library.)

Parker High School was described in a 1950 Ebony magazine article as “the world’s biggest Negro high school” and boasted an ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. Barriers: Black and White—One City, Two Worlds

- 2. Confrontation: Struggles against Segregation Intensify

- 3. Movement: Courageous Spirits Hit the Streets

- 4. Milestones: Changes to the Political Landscape

- 5. Memorialization: Remembering the Birmingham Movement

- Bibliography

- About the Organization