- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

California and the Civil War

About this book

In the long and bitter prelude to war, southern transplants dominated California government, keeping the state aligned with Dixie. However, a murderous duel in 1859 killed "Free Soil" U.S. Senator David C. Broderick, and public opinion began to change. As war broke out back east, a golden-tongued preacher named Reverend Thomas Starr King crisscrossed the state endeavoring to save the Golden State for the Union. Seventeen thousand California volunteers thwarted secessionist schemes and waged brutal campaigns against native tribesmen resisting white encroachment as far away as Idaho and New Mexico. And a determined battalion of California cavalry journeyed to Virginia's Shenandoah Valley to battle John Singleton Mosby, the South's deadliest partisan ranger. Author Richard Hurley delves into homefront activities during the nation's bloodiest war and chronicles the adventures of the brave men who fought far from home.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access California and the Civil War by Richard Hurley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de la guerre de Sécession. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

HistoireChapter 1

THE REMOTEST PLACE ON EARTH

Sailing westward around the tip of South America was a heroic undertaking in the early years of the nineteenth century. Only dire need or the prospect of great reward led skippers to drive their wooden ships into the howling ice storms and violent seas of the passage. Whalers and fur traders braved the Horn in those days, as did the Spanish and Mexican ships that sustained settlements along the Pacific shores. Until the advent of the steamship, passage from the Atlantic to the Pacific coast of North America remained a dangerous and costly business.

Access by land was even more challenging. Expeditions to California from Mexico crossed vast stretches of desert, where draft animals perished and mounted warriors from a variety of tribes attacked wagon trains almost at will. The central government of Mexico simply did not have the military resources to control what is now the American Southwest or even venture into it without the gravest precautions.

For citizens of the young United States, the Pacific coast was even more remote. More than 1,500 miles of mountain, prairie and desert separated the Mississippi Valley—the locus of American expansion in the 1830s and ’40s—from the western shores of the continent. Any attempt to reach the Far West also had to pass through the domains of numerous native peoples, whose response to white intruders varied from welcoming to lethal.

Adventurous Yankee trappers, traders and sailors did reach Mexican California in the first decades of the nineteenth century. They brought back tales of a rich country of excellent climate, governed by a small population of Mexican ranchers and soldiers along its coast and inland valleys but still under the sway of its original inhabitants everywhere else. These early American explorers also carried back word of the fabulous Bay of San Francisco, the great natural harbor of western North America—a still-water haven where all the navies of the world could ride safely at anchor.

The land route between Alta California and Mexico was extremely difficult and dangerous. Expeditions were heavily guarded and infrequent. Collection of Joe Pawlowski.

The strategic potential of San Francisco Bay was a magnet to any nation with ambitions in the Pacific. Great Britain and the United States sought to buy the harbor from a weak and divided Mexico, which desperately needed foreign currency. When Mexico refused all offers, the Polk administration, which assumed office in 1845 under the banner of “Manifest Destiny,” proceeded to make other plans. Later that year, the administration welcomed the breakaway Mexican province of Texas into the Union—an act that Mexico had repeatedly threatened to oppose with force. Texas’s admission was made all the more galling by the state’s claim that its border was marked by the Rio Grande. Mexico held that the Nueces River constituted the dividing line.

National pride was engaged on both sides of the dispute, and Mexican forces duly sallied forth to attack the troops Polk sent into the contested area by way of live bait. Bitter recriminations ensued, and the two nations prepared for war.

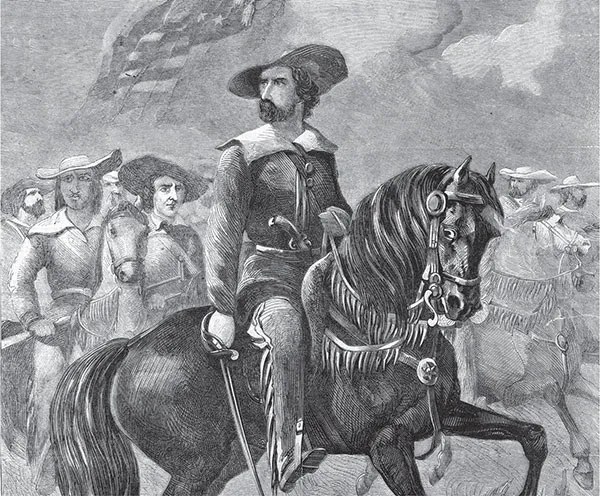

It was clear from the beginning that America’s aims extended far beyond Texas. Before news of the U.S. declaration of war reached California, Yankee settlers in the Sonoma Valley rose in the “Bear Flag” revolt, assisted by a party of sixty heavily armed “surveyors” under Captain John C. Frémont, who just happened to be in the neighborhood at the time. A few days later (and still before news of the U.S. declaration), Commodore John D. Sloat of the U.S. Pacific Squadron sent marines ashore to seize Monterey, the capital of Alta California.

Many native Californios had little use for the remote and ineffective government in Mexico City and were in favor of independence—or of gaining the protection of another power. In Sonoma, opposition to the Yankee rising had more to do with outrage at the high-handed behavior of the Bear Flaggers rather than opposition to American rule. Mexican resistance proved more determined farther south, where Andrés Pico and a troop of Californio lancers handed the American expeditionary force under Stephen Kearney a bloody check at the Battle of San Pasqual. In the end, Kearney’s force combined with sailors and marines of the Pacific Squadron and with Yankee settlers to quell Californio resistance. In January 1847, Mexican forces in California capitulated. The American conquest was sealed by victories won later that year in Central Mexico by Generals Winfield Scott and Zachary Taylor, who broke Mexico’s war-making power. In February 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo formalized the “Mexican Cession”—the transfer from Mexico to the United States of a landmass the size of Western Europe, comprising the future states of California, Nevada and Utah, along with parts of New Mexico, Arizona, Colorado and Wyoming. Mexico received $15 million in compensation.

In 1843, Captain John C. Frémont was sent to explore the Far West. His mission was to survey a route to Oregon for American settlers, who would forestall British occupation of the territory. Frémont also visited California—and went home full of enthusiasm for what he saw there. Library of Congress.

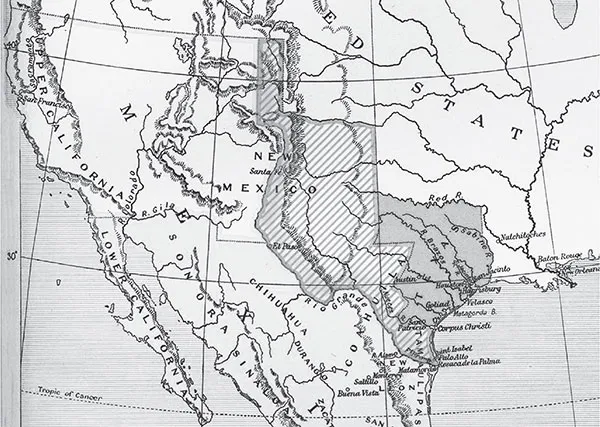

Mexico and the United States held different views about the size of Texas. The area in dispute (shown in diagonal hatching) was vast. Ironically, most of it was useless to white settlers, since great swathes of present-day Texas, New Mexico and Oklahoma were at that time under the control of the Comanche and their allies, who were not inclined to share. Base image courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, University of Texas at Austin.

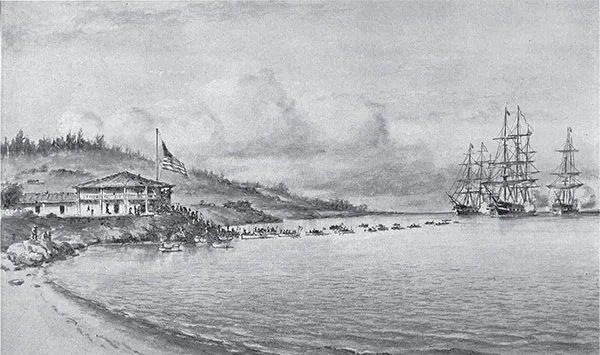

U.S. sailors and marines seized Monterey on July 7, 1846. Their commander, Commodore Sloat, was not the first American to take Monterey. In 1842, Commodore Thomas ap Catesby Jones of the Pacific Squadron had also raised the U.S. flag over the sleepy colonial town. Discovering that no war had been declared, the commodore apologized and sailed off. From The Life of Rear Admiral John Drake Sloat by Edwin Sherman (1902).

Nine days before the signing of this treaty, the defining event of California’s history took place. On January 24, 1848, a carpenter named John Marshall discovered gold in the tail-race of Captain Sutter’s sawmill at Coloma, in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada. Over the next two and a half years, a quarter million Argonauts—seekers of the Golden Fleece—poured in, transforming the remote colonial province into the bustling U.S. state of California.

Chapter 2

AMERICAN CALIFORNIA

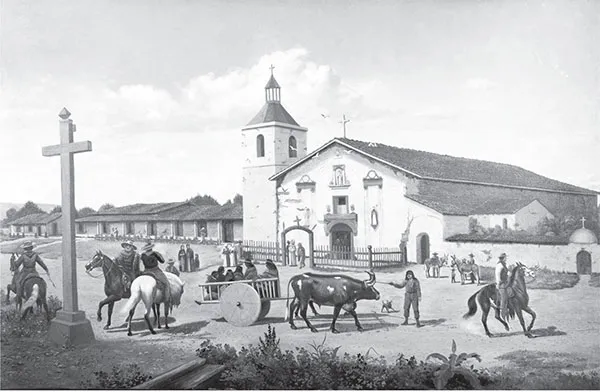

For millennia, California’s natural abundance supported a large population of native peoples. Pre-contact numbers are hard to estimate, but a commonly cited figure puts California’s indigenous population at about 300,000 at the beginning of Spanish colonization in the late eighteenth century. Waves of European-derived illnesses sliced through the Indian population, both at the crowded missions (which provided ideal vectors for disease) and along trade routes that offered European-born pathogens free passage around the province. By the 1840s, the native population had been reduced to half its original size but still vastly outnumbered settlers of European descent, who numbered fewer than 10,000.

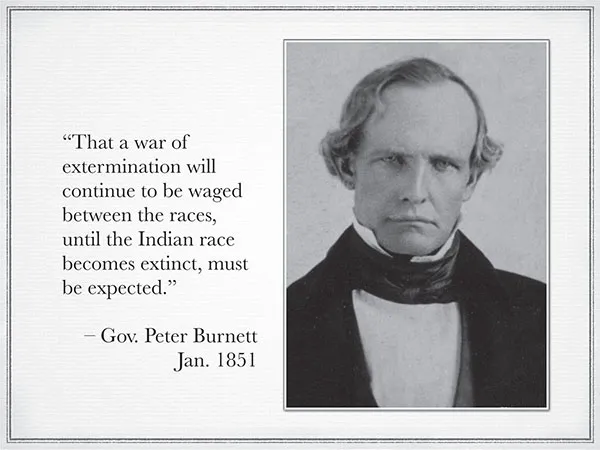

Both native and Mexican populations were overwhelmed by the onslaught of gold-seekers. California’s Indian population collapsed, cut down by disease, starvation, murder, forced relocation and social disruption. Tribes who numbered in the thousands in the mid-1840s virtually disappeared in the first decade of American rule. Survivors were systematically driven from the gold fields and herded onto remote reservations, where disease and vicious “ethnic cleansing” continued unchecked. Indian political power, which had been considerable in Mexican California, disappeared in this era and did not play a role in California’s experience of the Civil War. A few remote Indian tribes do enter the story, mainly as targets of military and paramilitary operations.2

California’s Mexican population, by contrast, continued to play a role in the state’s politics. Many Californios were substantial property owners—particularly in the southern half of the state—and their numbers were sufficient to retain a voice in the new society.

Mission Santa Clara, a crowded public place in California in the 1840s. Image provided courtesy of Archives & Special Collections, Santa Clara University Library.

California’s newly elected governor painted a dark picture of race relations in his first State of the State address. Wikimedia Commons.

San Francisco, a crowded public place in California in 1860. Library of Congress.

California’s gold rush coincided with a string of natural and man-made disasters around the world that displaced millions from their homelands. The Tai-ping Rebellion in China, the Irish Potato Famine and the brutal repression of Europe’s revolutionaries of 1848 sent out tidal waves of suffering humanity. For refugees who could afford the sea voyage, migration to the gold fields offered a radiant promise of new life.

Ultimately, the lion’s share of wealth and influence generated by gold mining fell to recent arrivals from the United States, the “Forty-niners,” who poured into California by the tens of thousands following Marshall’s discovery. These adventurers (almost all of them men) came from both North and South and brought their political beliefs, customs and social prejudices with them. They—and the tens of thousands of gold-seekers who arrived from Europe, China, Mexico, South America, Hawaii and Australia—formed the core of a new society that grew up almost overnight into the racial and cultural kaleidoscope that was American California. It was the interaction of these wildly differing peoples that determined the Golden State’s response to the great crisis that overtook the United States in the tenth year of California statehood.

Abandoned ships in Yerba Buena cove, San Francisco, 1849–50. Library of Congress.

The surge of adventurers into California from around the globe was unprecedented in human history—and the patchwork U.S. military command that was supposed to govern it was desperately under-equipped for the job. Soldiers and sailors who should have kept order joined the exodus for the gold fields, leaving behind empty barracks and ships. Merchant seamen also deserted en masse. San Francisco’s waterfront became a graveyard for hundreds of abandoned vessels, many of which lie there to this day under landfill.

INVENTING A GOVERNMENT

Mexican California’s civil government had been based on the office of the alcalde—a kind of mayor and justice of the peace—and the system persisted in established areas, as stipulated by treaty. But the floods of miners pouring out over the valleys and up into the foothills caused new towns and cities to spring up overnight. Such communities were governed—to the extent they were governed at all—by ad hoc arrangements. Law enforcement and the administration of justice were pretty much do-it-yourself affairs, with the unsurprising result that early American California was a chaotic and violent place.

General Bennet Riley, California’s last military governor, knew a thankless, impossible job when he saw one and acted swiftly to establish a civil government. Riley issued a decree in June 1849, calling for a convention to define California’s borders and draw up a state constitution. In September, delegates elected to this convention assembled in Colton Hall at Monterey. In October, they issued a proposed state constitution, which California voters approved in November (voters in this instance being defined as white male U.S. citizens over twenty-one and Mexicans who opted to become American citizens). All that remained, as far as these Californians were concerned, was for the federal government to welcome them into the Union as the thirty-first state.

Back in Washington, discussions about the government of the territories acquired from Mexico was proceeding slowly and painfully, due to bitter disagreement over the extension of slavery. California’s reques...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Praise

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Author’s Note

- 1. The Remotest Place on Earth

- 2. American California

- 3. In the Southern Orbit

- 4. The National Crisis

- 5. Which Way California?

- 6. Speaking for the Union

- 7. Securing the Golden State

- 8. Turmoil in the Southwest

- 9. The California Column

- 10.The Department of New Mexico

- 11. Life in Wartime California

- 12. Confederate Partisans

- 13. With Connor in Utah

- 14. Californians Fight Back East

- 15. The Sanitary Commission

- 16. Aftermath

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author