- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hidden History of Napa Valley

About this book

Napa Valley is known for its wine and winemakers, but just beneath the fertile soil lies another, more complex version of its history. Uncover the story of Napa's first Chinatown--once home to nearly five hundred immigrants--that dwindled to fewer than seventeen residents before the last buildings were razed in the early twentieth century. Meet the small but determined group of African American farmers and barbers who called Napa home and the indomitable May Howard, a successful businesswoman and brothel owner. Learn about the Bracero Program that kept many of Napa's wineries, including Krug, Beaulieu and Stag's Leap, thriving during World War II. Join author Alexandria Brown as she explores these lesser-known stories of the ordinary people who helped shape modern-day wine country.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Hidden History of Napa Valley by Alexandria Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

FIRST PEOPLE

The white people came along and destroyed all these places.

They’re just cutting us off when all our rights have been cut off.

—Laura Fish Somersall

1

TALAHALUSI

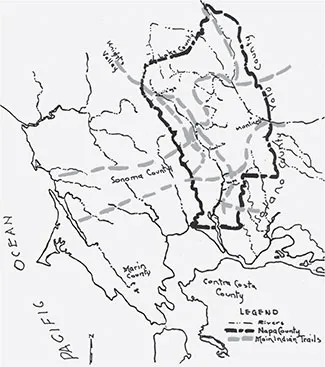

Sometime between three thousand and ten thousand years ago, the first people arrived in what is now Napa County. Over time, the majority of the region would become home to the Wappo and Southern Patwin people. The territories of the Pomo and Miwok also crossed into present-day Napa County, but they predominantly lived in Marin, Lake, Sonoma and Solano Counties. The Wappo were the earliest known settlers in the valley they called talahalusi, or “beautiful land.”

Although we know them today as the Wappo, they historically referred to themselves by their tribelet names: Mishewal, Mutistul and Meyakama. “Wappo” may be an English corruption of the Spanish word guapo, or “brave,” presumably derived from their staunch opposition to Spanish invasion. They spoke a dialect of Yukian, one of the state’s oldest language families. Some of their terms influenced Spanish and American place names: the Mayacamas Mountains and Rancho Mallacomes (also called Rancho Muristul y Plan de Aqua Caliente) come from the Meyakama (“water going out place”) and Mutistul tribelets, Rancho Caymus from the Kaimus village and Sonoma from the ending phrase -tso nóma, meaning “campsite.”

Within the tribelets were villages and campsites with a variety of structures made of thatched grass. Each had at least one sweathouse. Villages were headed by a chief, a person of any gender who was appointed for life. Wappo chiefs supervised ceremonies, resolved intra- and intertribal conflicts and directed hunting and fishing expeditions.

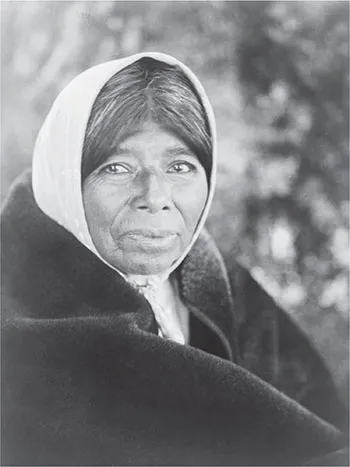

An unidentified Wappo woman photographed around 1924 by Edward S. Curtis. Courtesy of Library of Congress.

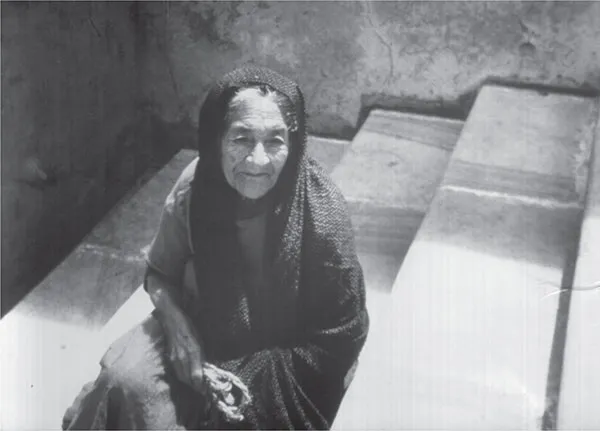

An undated photo of an unidentified Wappo woman. Courtesy of Napa County Historical Society.

Wappo people also controlled access to the obsidian-rich Napa Glass Mountain, a volcanic peak south of Howell Mountain. Obsidian was used for arrowheads, knives and other tools and was traded extensively throughout California and the West. All genders made baskets, but women produced the bulk of them. As basketmakers, their skill was unparalleled. Like obsidian, baskets were important elements of daily life. There was a basket for just about everything from cradles to food storage to trapping fish and game and everything in between.

The other inhabitants of the valley were the Southern Patwin. Patwin territory was large, ranging from the San Pablo and Suisun Bays up the Sacramento River to Colusa County and west to the eastern hills of Napa County. The southern and western portions of that territory, including Putah Creek and down through Napa to Suisun Bay, were home to the Southern Patwin. The word patwin, although today used to describe a related group of people, simply means “people.” Within the Southern Patwin were numerous tribelets that were linguistically and culturally related but politically independent.

Southern Patwin tribelets had a central village and several nearby settlements containing sweathouses, dance houses and homes built partially underground and sealed with earth. Some of those village names might sound familiar: Napato, Tulukai and Suskol eventually became Napa, Tulocay and Soscol. Each settlement had its own leader, and the central village was led by a chief. This leader was usually a man who inherited the role, but succession could be disputed by village elders. Local leaders dealt with intergroup conflicts so the chief could focus on ceremonies, food-gathering expeditions and other larger community needs.

In general, Wappo and Southern Patwin people established villages alongside or near waterways, particularly Putah Creek, the Napa River and their tributaries. They took full advantage of the bounties the land had to offer. Fish and shellfish were hauled out of the rivers and creeks, while deer, waterfowl, rabbits, bears and other game were hunted in the forests and chaparral. Acorns formed the bulk of their diets, but honey, berries, bulbs, roots and clover were favorite additions.

Although no traditional Indigenous village sites within Napa County are in active use by the descendants of the original occupants, evidence of their lives abounds. Lots of locals have collections of mortars, pestles, grinding stones and arrowheads they have found throughout the county. Occasionally, construction projects are converted into temporary archaeological sites by the discovery of Indigenous artifacts. In April 2018, the most recent large-scale excavation wrapped up. The site, an eleven-acre plot of land near Silverado Trail and First Street, is set to become a 351-room luxury hotel. Work stopped for nearly a year as archaeologists unearthed potentially historically significant artifacts. Sadly, many villages, campsites, burial grounds, obsidian quarries and shell mounds have already been lost to time, desecration and destruction.

Hand-drawn map of the North Bay Area showing some of the common trails used by Indigenous people. Courtesy of Napa County Historical Society.

A 2012 photo of a mortar rock possibly used by the Wappo. Found in the Dry Creek area and placed on the grounds of the old courthouse in 1942, the rock was believed to have been in use for several hundred years. Courtesy of the author.

2

INVASION

Nearly three centuries after Columbus first landed in the New World and kick-started more than half a millennium of European theft, enslavement and exploitation, Franciscan Fray Junípero Serra established the first mission in Alta California. Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the Catholic church built twenty-one missions along the California coastline. When a new mission opened, padres and soldiers made excursions into the nearest villages to baptize Indigenous people and send them back to the mission as de facto slaves. Later, they sent neophytes out to proselytize to unconverted villages and recover runaways.

How the Spanish treated Indigenous people was not dissimilar from how white Americans in the South treated enslaved Africans. Without the forced, unpaid labor from Indigenous neophytes, the mission system could not survive. Their work tending crops and stock animals, constructing buildings and manufacturing goods provided food and products to the missions as well as nearby settlers and military bases and outposts.

Mission life was harsh for Indigenous residents. Physical, verbal and sexual assault by Spanish and Mexican padres and soldiers were everyday occurrences, and disease and starvation were unavoidable. In 1826, Frederick William Beechey, a captain in the United Kingdom’s Royal Navy, recorded how Mass was held at Mission San José. He wrote that officers with whips, canes and goads (a type of pointed stick used to drive cattle) were stationed in the center aisle of the chapel to enforce compliance and silence in the Wappo, Patwin, Miwok, Ohlone, Yokut and others. At the back were soldiers armed with bayonets to block escape. By 1834, nearly 2,300 Southern Patwin and 550 Wappo had been sent to Mission Dolores (founded in San Francisco in 1776), Mission San José (Fremont, 1797) and Mission San Francisco Solano (Sonoma, 1823).

Napa tribes were well aware of the horrors being perpetrated against their neighbors, so when Lieutenant Gabriel Moraga crossed the Carquinez Strait in 1810, the Southern Patwin were ready to fight. Moraga was dispatched as retribution for the Suisunes, a tribelet who lived in southern Napa and Solano Counties, killing sixteen Mission Dolores neophytes. During the three-day raid, Moraga’s men slaughtered and scattered much of the village of Yulyul, now Rockville, and burned to death the chief and his top warriors. Several children were captured and sent to Mission Dolores, including Sina, baptized as Francisco Solano. As an adult, he became Chief Sem Yeto, commonly known as Chief Solano, for whom his home county was named. At his height of six feet and seven inches, Sem Yeto made an imposing leader.

When General Mariano Vallejo was sent to quell Native opposition to Mexican settlement in 1835, he and Chief Sem Yeto clashed in the Battle of Suscol near present-day American Canyon. Sem Yeto rallied hundreds of Suisunes and members of neighboring tribelets to the battlefield. At first, they successfully routed Vallejo; then, Vallejo’s reinforcements arrived. The two sides agreed to a treaty that secured Mexico’s dominance in the North Bay and protected the Suisunes. Sem Yeto and Vallejo became fast friends and close allies. Sem Yeto received Rancho Suisun for his dedication, becoming one of only a few Indigenous Californians to get a land grant. He supposedly died in 1850, but Mariano’s son Platon claimed Sem Yeto lived until at least 1858. According to Platon, Sem Yeto went north to Alaska after Vallejo was taken prisoner during the Bear Flag Revolt before returning to California.

The first Mexican foray into Napa Valley took place in June and July 1823, thirteen years after Moraga’s massacre. Fray José Altimura and a contingent of Mexican soldiers and Indigenous neophytes, including Sem Yeto and other Suisunes, left Mission Dolores looking for a site to found a new mission. Over the next two and a half weeks, they journeyed to Petaluma and Sonoma, then down to Carneros and Napa. Altimura preferred Sonoma to Napa, so that was where they founded Mission San Francisco Solano. Soon, they began bringing in Wappo from the valley.

In 1833, Mexico secularized the missions. The Catholic Church, stripped of its ownership of the missions and their outlying territories, could no longer hold Indigenous people captive. The mission system quickly collapsed. Many were unable to return to their ancestral lands, which had been colonized by Californio settlers and soldiers, and found themselves stranded without housing or employment. Landowners and ranchers swooped in. In reality, one set of slaveholders replaced another. Colonel Salvador Vallejo, Mariano Vallejo’s brother and the owner of Ranchos Napa and Yajome, detailed the work they did for him:

This buckeye tree on Suisun Valley Road near Rockville was believed to be the burial site of Chief Sem Yeto. The tree was cut down many years ago to widen the road. Undated. Courtesy of Napa County Historical Society.

They tilled our soil, pastured our cattle, sheared our sheep, cut our lumber, built our houses, paddled our boats, made tiles for our houses, ground our grain, killed our cattle, and dressed their hides for market, and made our unburnt bricks; while the indian [sic] women made excellent servants, took good care of our children, made every one of our meals.

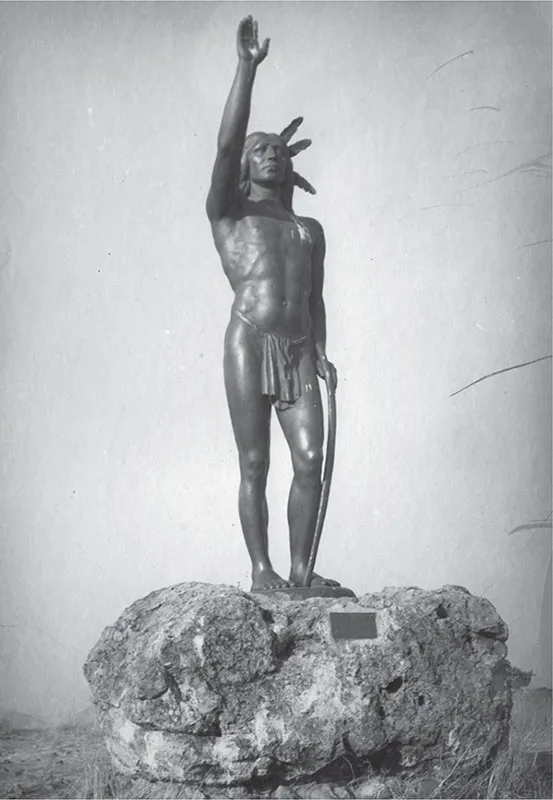

The twelve-foot-tall bronze statue of Chief Sem Yeto was created by William Gordon Huff in 1934. After repeated acts of vandalism, the statue was moved to the library and is now in the Solano County Events Center. Courtesy of Napa County Historical Society.

The first floor of the Longwood Ranch house was Salvador Vallejo’s 1846 adobe. It burned down in the 1970s. This photograph was taken in 1933. Courtesy of Napa County Historical Society.

The transfer of California from Mexico to the United States in 1848 further separated the Wappo and Southern Patwin from their homelands. Californios gave way to Americans, and the exploitation of Indigenous labor continued. Throughout the latter half of the 1800s, numerous Indigenous people worked the migrant labor circuit in Napa Valley while others resided in the county to work on farms as ranch hands and laborers or in private homes as domestic servants. Others moved to cities for work. Those who wanted to live traditionally were pushed north to Clear Lake as Americans bought up all the Napa Valley land.

Some American ranchers preferred the brutal mission-system labor model. On Charles Stone and Andrew Kelsey’s Big Valley Ranch in Lake County, the Eastern Pomo and Clear Lake Wappo were subjected to near constant starvation, torture, rape, captivity and murder. Stone and Kelsey, along with many other Americans, also practiced chattel slavery by buying and selling Indigenous people. In December 1849, eighteen-year-old Hoolanapo Pomo laborer Shuk (later called Chief Augustine) lost a horse while trying to find food for his people. Exhausted from years of torment and believing his mistake could potentially lead to a painful death at the hands of Stone and Kelsey, he and several other Wappo and Pomo people killed them. Shuk also had a personal motive: the Americans had imprisoned his wife and were raping her. The Wappo and Pomo fled the property, well aware of the history of bloody retaliation for defying the will of Mexican and American colonizers. They expected revenge, but what they got instead was one of the deadliest extermination campaigns in California history.

An American cavalry troop stationed in Sonoma set off to punish the Big Valley Ranch crew. Along the way, they stopped in a Wappo village just south of Calistoga. Even though they knew this group of Wappo had nothing to do with Big Valley Ranch, the cavalry shot to death thirty-five people anyway. They then killed a few more working on another nearby ranch. Meanwhile, Sonomans formed vigilante squads to drive out the local Coast Miwok, Pomo and Wappo. Throughout February and March 1850, two posses murdered their way through Napa and Sonoma Counties. The posse led by John Smith and Samuel Kelsey, Andrew’s brother, stopped first at George Yount’s ranch. Yount defended his laborers, mostly Kaimus Wappo women and children, but the attackers burned their homes and belongings and drove them into the Mayacamas. They did the same at a ranch near Calistoga and on Nicolás Higuera’s land near Napa city. They were finally stopped just before raiding Cayetano Juárez’s property and attacking his Southern Patwin laborers.

The assailants were rounded up and sent to jail, but after they were released on bail, their cases were dropped. Some of the perpetrators left town, but the violence was not over. That May, the military launched an all-out assault on the Pomo and Wappo camped around Clear Lake, many of whom were uninvolved with Kelsey and Stone. Exactly how many men, women and children were killed at the Bloody Island Massacre is undetermined—some say at least sixty, others as many as eight hundred—...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half-Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- PART I: FIRST PEOPLE

- PART II: ALTA CALIFORNIA

- PART III: STRUGGLE & PROGRESS

- PART IV: STRANGERS IN A STRANGE LAND

- PART V: THE BRACERO PROGRAM

- PART VI: WOMEN’S WORK

- PART VII: INDUSTRY

- PART VIII: INNOVATION

- PART IX: LOST AND GONE

- Bibliography

- About the Author