- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Irish Iowa

About this book

Iowa offered freedom and prosperity to the Irish fleeing famine and poverty. They became the second-largest immigrant group to come to the state, and they acquired influence well beyond their numbers. The first hospitals, schools and asylums in the area were established by Irish nuns. Irish laborers laid the tracks and ran the trains that transported crops to market. Kate Shelley became a national heroine when she saved a passenger train from plunging off a bridge. The Sullivan family became the symbol of sacrifice when they lost their five sons in World War II. Author Timothy Walch details these stories and more on the history and influence of the Irish in the Heartland.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

PIONEERS

It was not the land that attracted the first Irishmen to Iowa. To be sure, they could not help but be impressed by the sight of endless, waving grass as far as the eye could see. There was nothing like it in Ireland, where they had farmed small plots of land broken up by hedgerows.

What lured these pioneers was a dull but valuable metal called lead. News of lead deposits west of the Mississippi River attracted an adventurous breed to the mining town of Galena in Illinois. These men coveted the rich deposits on the riverbanks, but they crossed the Mississippi at their own peril. In 1830, the land that is now Iowa was controlled by the infamous Chief Black Hawk.

But the lure of that dull metal was impossible to resist, and in the spring of 1830, a group of miners took possession of the lead deposits in what would become the frontier town of Dubuque. Many were Irish—men named Dougherty, McDowell, McCabe, Murphy, O’Regan and Curran. They did not wear their nationality on their sleeves; they were miners. And yet they never forgot their heritage.

In crossing the Mississippi in 1830, these men were breaking the law. The United States government had deeded the land to Black Hawk and promised to keep the white man—Irish or not—east of the river. And as soon as the authorities learned that miners had crossed to the West, federal troops drove them back across to Galena. For the government, peace with Black Hawk was far more important than a few more lead mines.

The lead miners were a stubborn lot, however. Over the next three years, they fought with soldiers and Indians alike. Black Hawk’s War, as the conflict came to be known, was a sad affair that ended with the chief ceding much of northeast Iowa to the white man. By the middle of 1833, four to five hundred settlers had crossed the river to begin the settlement of Iowa; many of these pioneers were Irish.

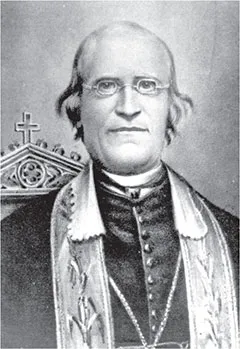

Bishop Mathias Loras was tireless in his efforts to attract Irish immigrants to his new diocese. Courtesy of the Center for Dubuque History.

Their fortunes were mixed. Without question, these Irishmen were adventurers. Who else would settle west of the Mississippi in the 1830s? Aside from the miners, they were a motley crew: a few were entrepreneurs who became city leaders, but many were laborers and shopkeepers. They all contributed to the hustle and bustle of early Dubuque.

It was, of course, the mining operations that were the focus of early attention. The work was hard, and the Irish looked for every opportunity to escape the burdens of life in the mines. Not surprisingly, the saloons of Dubuque became the Irishmen’s social club, and many miners drank and gambled away their pay.

One antidote to frontier hardship was religion. As Catholics, the Irish of Dubuque sought out the services of a priest. As if by divine intervention, Father Charles Van Quickenborne arrived in Dubuque in July 1833, little more than a month after the main body of settlers. Shortly after his arrival, Quickenborne baptized the son of Patrick and Mary Monaghan, making Henry Monaghan the first Catholic to be baptized in the territory.1

Quickenborne’s stay was productive. He celebrated Mass each day at the home of a “Mrs. Brophy” and set up a committee of local Catholics to raise funds to build a church. Among the members of the committee were James Fanning, James McCabe, Patrick O’Mara and Thomas Fitzpatrick, all Irish immigrants.

Quickenborne left at the end of the summer to be replaced in 1834 by an Irish-born priest named Charles J. Fitzmaurice. Upon his arrival, Fitzmaurice learned that the church committee had already purchased land and raised over $1,000 to build a church.

That bit of good news was the one bright spot in a hard life for the missionary. Among his first pastoral responsibilities was to minister to an Irishman named Patrick O’Connor who had been convicted of murder. His condemnation of those involved in the affair would isolate Fitzmaurice from his flock.2

There was no dispute over the facts of the case. In the fall of 1833, O’Connor had shared a cabin with a fellow miner named “O’Keaf.” Returning with provisions one rainy day, O’Keaf asked O’Connor to open the cabin door. O’Connor refused, so O’Keaf pushed the door open. O’Connor’s response was to shoot and kill his cabin mate.

Justice on the frontier was swift. The miners held a trial and condemned O’Connor to death on June 20, 1834. Fitzmaurice knew that the trial was not legal, and he was determined to stop the hanging.

Marshaling all of his religious authority, the priest condemned those involved and called the decision to hang O’Connor illegal and unjust. Although new to the community, Fitzmaurice carried some weight with the Irish. His appeals would be for naught, however, and O’Connor was marched to the gallows.3

True to his religious convictions, Fitzmaurice stayed with the condemned man until the very end. He heard O’Connor’s confession and ministered the last rites of the Church. In fact, the two men—priest and penitent—rode together to the execution in the condemned man’s coffin!

Fitzmaurice’s involvement in the case also had an unintended consequence. A rumor spread within the community that a band of armed Irishman was on its way from Wisconsin intent on freeing O’Connor. Although the story was false, it galvanized the non-Irish miners who shouldered their weapons and proceeded to carry out the sentence.

Father Samuel Mazzuchelli was an Italian missionary priest who worked among many Irish communities in Iowa in the years before the Civil War. Courtesy of the Center for Dubuque History.

The tangled lives and tragic deaths of O’Connor and O’Keaf were an auspicious beginning for the Irish in Iowa. For many, the notoriety of the incident confirmed the worst fears of Irish and non-Irish alike: that the Irish were too temperamental to contribute to the establishment of a new state.

Even Fitzmaurice could not escape the tragedy. Distrusted by many for his controversial efforts to save O’Connor, the priest had little impact on the moral life of this frontier community. He died in a cholera epidemic early in the spring of 1835.

Other Irish pioneers were spared the tragedy that gripped O’Connor, O’Keaf and Fitzmaurice. John Foley and Patrick Quigley, for example, were elected to serve Dubuque in the Wisconsin Territorial Legislature. And many of the two hundred Irishmen living in Dubuque in 1835 became wealthy from lead mining.

Ironically, it was an Italian-born missionary priest who brought peace to the troubled souls of the Irish in Iowa. Father Samuel Mazzuchelli arrived in Dubuque in July 1835, and with the aid of Patrick Quigley, the priest set up a chapel in a spare room of the Quigley home. He also convinced the Irish to fulfill their pledges to build a permanent church. Perhaps a better indication of his popularity was the fact that even non-Catholics contributed to the building campaign.4

The cornerstone was laid in August, but progress slowed, and the church was not ready for worship services until late in the fall of 1836. Indeed, the building would not be finished until 1839. By then, Mazzuchelli had moved on to other communities in the state in need of a priest.

Peace, however, was no guarantee that the Irish population would move west to the Iowa frontier. The work would be hard, and the need was limitless. Men had to clear the forests, break the prairies, lay out the roads and build the bridges. And if Iowa was to prosper, immigrants were needed to bring the railroad to the state. Frontier Iowa was a land of promise, and the pioneers who had crossed the Mississippi had to convince their fellow countrymen in the eastern cities to venture west.

It is hard to use the term “promotion” in the context of the 1840s, but that is what the first Irish Iowans did in sending letters back east to local newspapers. They boasted and promised the Irish immigrants of New York, Boston and Philadelphia that they should move west to find prosperity.

It was destiny and perhaps God’s will that the Irish should move west. “Of all the foreigners,” wrote one correspondent in the Burlington Hawkeye in 1844, “none amalgamate themselves so quickly with our people as the natives of THE EMERALD ISLE. In some of the visions which have passed through my imagination, I have supposed that Ireland was originally part and parcel of this continent and that by some extraordinary convulsion of nature, it was torn from America and, drifting across the Ocean, it was placed in the unfortunate vicinity of Great Britain.”5

The readers of the Hawkeye, the leading paper of the Iowa Territory, must have been impressed. That the Irish were needed in Iowa was without question, but more had to be done to convince them to leave eastern cities and venture west. To validate this gamble, the Irish needed to hear directly from fellow Catholics who had already established themselves in the state.

Throughout the 1840s, a committee of Iowa Irishmen wrote to Catholic newspapers in New York and Philadelphia with letters about the opportunities available across the big river. Led by Charles Corkery, the committee validated the reality of prosperity. “My sole desire,” wrote Corkery to the Philadelphia Catholic Herald in July 1841, “is to direct the attention of Catholics (Irish Catholics more particularly) to the country little known and less appreciated in the East.”6

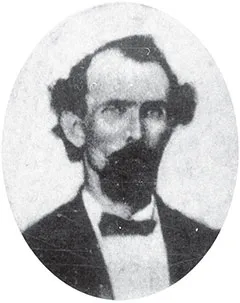

Charles J. Corkery worked closely with Bishop Loras to attract his fellow countrymen to Iowa—“the Eldorado of the West.” Courtesy of the Center for Dubuque History.

And Corkery wanted to assure readers that the appeal of the West was not unique to him. He was no huckster. He spoke for the Irish who were already living in Dubuque and Davenport and the eastern counties of the Iowa territory. “I have had ample opportunities of bearing witness,” intoned Corkery, “to the testimony of many able and respectable writers (travelers and others) who unite in giving Iowa the happy cognomen of ‘the garden of America.’ The Eldorado of the West.”

Corkery may have had a touch of hyperbole in his prose, but he knew how to entice his fellow countrymen who hungered to return to the land—to plant crops as they had done in the old country. “Irishmen unite in saying,” he added, “that our wheat and oats are nothing inferior to those of Ireland and I have never seen better potatoes in Ireland than those raised in [Iowa].”

Corkery and his committee were joined in their campaign by Bishop Mathias Loras of Dubuque. Although not of Irish heritage, Loras understood implicitly that his new diocese would benefit greatly by devoted communicants who already spoke the English language. Together, Corkery and Loras wrote numerous letters to the Boston Pilot and other Catholic papers throughout the 1840s and 1850s. “Let good emigrants come in haste to the west of Iowa,” wrote Loras in 1854. It was both a command and an invitation.7

But some of the Iowa Irish were concerned about making too much of the opportunities in their new state. Michael O. Sullivan of Dubuque, for example, cautioned emigrants to be prepared for hard work. “They must not be too sanguine,” he warned. “They must consider the genius of a rising community. They must not be shocked at the idea of living in a log cabin or wearing rough clothing and, at first, of sacrificing many things they enjoyed in the old home. If they come fortified with industrious and steady notions they will certainly prosper.”8

Indeed, they would prosper. During the 1840s, numerous Irishmen crossed the river and purchased land in Dubuque, Jackson, Linn, Johnson and Jones Counties at a cost of four to eight dollars per acre. Impoverished emigrants unable to purchase their own land could work for hire at a rate of thirteen dollars a month plus room and board. It was a hard life but well worth the effort. As Sullivan noted in a second letter to the Pilot, many of the first emigrants to the Iowa territory who had started with a few acres now owned 160 to 640 acres and had no debt.

But a pioneer’s life was not for everyone. James McKee, an early Irish resident of Washington County wrote to a friend in Pennsylvania about his new life and land. “I shall not attempt to describe the appearance of the country,” McKee wrote in July 1848. “But there is one thing I know: that it does not suit any old country man to get into the timber and make a farm. It is enough to discourage them. I know that it has done so with a great many.”9

And yet McKee did not want to discourage his friend to come west. “If you want to get a farm,” he wrote, “this is the place for you.” Just as important, McKee notes the sense of democracy and liberty that came with being your own man in a new land. “These people are more on an equality with one another than they are [in Pennsylvania]. Should you come out here, I hope it will not be long.”

McKee had one final piece of advice for his friend: don’t be too much of an Irishman. “If I am able to render any service, [it will be] that people will be calling you a ‘green’ Irishman. Do not be rash in speaking your sentiments to any ‘country-born’ respecting the Emerald Isle—or anything pertaining to it.”

Sullivan, McKee and the first Irish to settle in Iowa provided good advice to the second wave of settlers who arrived in the 1840s. The value of their advice was evident in the settlements that emerged quickly in the 1840s in th...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Pioneers

- 2. Farewell to Famine

- 3. Faith of Our Fathers

- 4. Sisters of Erin

- 5. City Slickers

- 6. Country Folk

- 7. Their Daily Bread

- 8. “I Am of Ireland”

- 9. “No Irish Need Apply”

- 10. Hills and Dales

- 11. Depression and War

- 12. Forever Irish

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- About the Author

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Irish Iowa by Timothy Walch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.